Graham Reid | | 9 min read

Academics are a pretty sniffy bunch sometimes, says Bryan Sykes. Which would be an amusing observation if this professor of human genetics at the University of Oxford was laughing. But his assessment is delivered as a dust-dry observation with the same unswerving clarity he brings to his research on the genes, chromosomes and other invisibles which make up human life.

His language is telling -- the implication behind "academics" which suggests he stands apart, the use of a lazy adjective latched on to the common phrase. It is a sentence emblematic of Sykes, who has been a populariser of his area of study and often addresses an audience unschooled in the more arcane areas and scientific language of his chosen field.

In his book, The Seven Daughters of Eve, this acclaimed researcher, scientific adviser to Britain's Parliament, television commentator and founder of an ancestor-finding company, identified seven women from whom he reasoned 650 million living Europeans are descended. To these women -- who lived between 45,000 and 20,000 years ago -- he also gave names to humanise them and break the conventional view that mankind's tribes were a homogeneous bunch of hairy bi-peds.

His point in naming is to remind us that we are all individuals, even these smelly types which we might not recognise as Helena, Tara, Katherine, Jasmine or the others. And individuals make the changes.

Sykes is used to ruffling feathers in academia and bringing his research to those who have maybe never studied science and might be a bit scared of it.

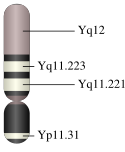

His latest book Adam's Curse -- which projects the literal demise of human males through irreparable damage done to the man-making Y-chromosome -- is written in his anecdotal style. His narrative begins with the observation "the experiment which gave us men is not turning out too well" (he cites acts of violence and aggression) and moves through being invited to speak at a Glaxo-Wellcome conference, a company chaired by his namesake, Sir Richard Sykes.

The coincidence of their identical surnames prods his imagination. He asks the businessman for a tissue sample, then proceeds to analyse it to see if they are genetically related. He finds that they are related in the distant past, and even locates the moorland stream (in Yorkshire, a "sike") where their common ancestor lived. From there he introduces the intelligent lay reader to the world of chromosome analysis, genetic encoding, and a discussion of the unique but damaged Y-chromosome.

This is science as a journey of discovery, and Sykes is an enjoyable, informative guide. He personifies chromosomes and genes as if they made conscious decisions. It is a device which has been used before -- he name-checks zoologist Richard Dawkins, author of The Selfish Gene among others -- as a way in which we can see how things might happen.

"Of course there is no conscious thought involved, genes and chromosomes have no thought for the future. It's to try and make it easier to understand.

"To be honest, I get annoyed with people in the field I'm in -- human genetics, the past and so on -- when they want to keep it all to themselves. Absolutely ridiculous.

"You have to use different types of language, different devices, when you're writing for an audience who haven't come across all the words and phrases. I haven't had anybody say, 'This is simplifying to the point of banality'. But you know, academics are a pretty sniffy bunch sometimes."

While some have mildly disagreed with his populist approach, few have seriously challenged his research in which he says the Y-chromosome which makes for maleness -- and by extension aggression -- has undergone a genetic hammering down the centuries and, being unique, is unable to heal itself by pairing with another similar. The male blueprint is headed for extinction. That's still some way off -- maybe 100,000 years at the earliest -- but his claim has led to amusing headlines.

Britain's Sunday Times offered "Bad news: men doomed. Good news: no problem". The "good news" was because Sykes argues humans -- men included -- will survive through designer chromosomes which can be replicated through DNA synthesis and spliced into other chromosomes to continue the species. Males may, or may not, be needed or present in this distant future.

If the prospect of a male-free environment gives comfort to lesbian separatists, Sykes hardly lets women off for the climate of aggression and violence. Women, through sexual selection, gravitate towards men who are powerful and wealthy, attributes which have been achieved through dominant or aggressive behaviour.

"I think that is unfortunately the case, not in every example, but there are many studies that wealthy men have far more sexual encounters than poor ones, even in our society. I do think the Y-chromosome which, like all genes can be incredibly selfish, has benefited tremendously from the rise in concepts of wealth of property.

"There's a cycle of sexual selection based on male evolution, social evolution too, which is to some extent driven by female choice. This is a very well-known phenomenon in the animal world. The animal equivalent is the tail of the [male] peacock which grows fantastically ornamental and is driven essentially by female choice.

"I'm making a parallel to the accumulation of wealth and property, status and power - and they are actually driven by female choice in a preference for those qualities. The consequences of that have shaped our world, every aspect. The accumulation of wealth and power and influence knows no bounds, unlike the peacock's tail which can only grow so big until the peacock can't even take it off the ground.

"But at the same time the Y-chromosome is intrinsically feeble and decaying. There is an irony in that this very influential Y-chromosome is itself very weak."

That irony -- which Sykes characterises as "Gaia's Revenge" in Adam's Curse -- has parallel dimensions: that sperm counts are falling rapidly, and that Mother Earth/Gaia is hitting back at the level of conception.

"I haven't read any criticism for saying that, but I'm sure there is. I wanted this book to make people think, as well as enjoy and inform them, that there are powerful genetic and evolutionary spirals which can run out of control. We are not immune from them. We tend to think animals and plants evolve, but humans somehow escape, or have grown beyond these fundamental laws. I think the reverse is true really."

Controversially, Sykes also speculates on the "gay gene" and that there is genetically embedded war going on in which the mother's mitochondrial DNA attempts to "kill" the Y-chromosome and that trait is passed through the female line.

"It's a fairly revolutionary idea but not, by any means, unknown in the animal insect world. There is no doubt if you are looking at it from mitochondrial DNA's point of view, they really have no interest in a woman producing sons at all -- any more than Y-chromosomes have an interest in women producing daughters.

"They, alone among all our genes, are absolutely committed to the propagation of either females in the case of mitochondrial DNA, and males in the case of the Y-chromosomes. So they will be at war."

Sykes acknowledges his sociological perspectives of genetics -- thinking about things from the chromosomes' point of view -- raises questions about whether behavioural factors or indifferent science are driving the course of change.

Genghis Khan's aggressive behaviour -- widespread conquest, rape and seduction resulting in 16 million descendants carrying his chromosome -- raises questions: was he driven to success in war and bed by the ambition of his Y-chromosome, or is the spread of his chromosome a consequence of his sexual exploits and military conquests?

"If you were looking from the point of Genghis Khan's Y-chromosome, his behaviour has done it a power of good really. It's really, 'Who is driving what?' "

But Khan's male descendants may be on the way out if their Y-chromosome is irreparably damaged.

Yet some findings suggest the male-making gene isn't quite as impaired as Sykes believes. Researchers in Massachusetts have discovered the Y-chromosome has the capacity for self-repair. It has a unique way of repairing and re-pairing itself by linking with its own genetic "letters" because its genome sequence is a mirror-image much like a palindrome -- an arrangement of letters which reads the same backwards as forwards. That means there is an identical pattern of letters elsewhere it may be able to recombine with.

Sykes says the discovery is astonishing, but notes the gene conversions are all internal ones. It is still a lone chromosome without the ability to talk to others.

"I think what happens is the sequences are able to look at each other in the mirror and can convert its mirror image. It is a very exciting finding, but I don't think it means the Y-chromosome is in the same position as the other chromosomes in respect to being able to repair itself well and communicate with other chromosomes like all the rest can."

This is a rapidly evolving area of research, and Sykes cautions that predictions are just that. "They're not necessarily going to pan out."

Even the lay person engaged by Sykes' research -- and there are many, business is booming for his company www.oxfordancestors.com which allows people the chance to discover their ancient ancestors and explore their genetic roots -- must wonder about the validity of projecting a future which may never come.

"In regard to the question 'What's the point of all this?', a lot of genetic research now is trying to predict individual health outcomes and so on. The kind of work I've been doing has been using DNA to try to understand historical events, and try to reconstruct those. But then, because of the things I find, the patterns of Y-chromosomes, I consider the reasons for that and predict what might happen.

"We may not be here in another 1000 or 10,000 years. Yet if there is a genetic explanation for this then the sooner we realise it, the better. We have to become aware we're being driven by powerful evolutionary forces.

"Awareness is one stage, however, I think it's so difficult to stop. I'm doubtful whether we'll ever be able to do it because it's just such a strong spiral."

Adam's Curse: A Future Without Men by Bryan Sykes

post a comment