Graham Reid | | 8 min read

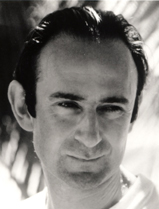

Five floors up in a swanky Auckland hotel room someone else is paying for, Oliver James should be happy enough, but he's concerned. He is grappling with the issue of happiness. Or more specifically the lack of it.

James is asking a knotty question: why is there more unhappiness among the middle-classes of the developed countries than there was previously? The average 25-year-old American today, he says, is between three and 10 times more likely to be depressed than their counterpart in the 50s.

And often these unhappy people are winners in the lottery of life.

"The British media has an endless stream of stories which have become a cliche: the highly successful person who has had to go to the Priory [an expensive psychiatric clinic in London] because they are feeling of incredibly low status -- even though everybody wants to have sex with them, everyone thinks they are wonderful and they are rich and have everything. How can that be?"

The British clinical psychologist, Observer columnist, documentary producer and author has been grappling with such issues for a decade. The titles of his books tell you as much: Juvenile Violence in a Winner-Loser Culture and Britain on the Couch: Why We're Unhappier Compared with 1950, Despite Being Richer.

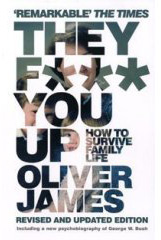

His current book, They F*** You Up: How to Survive Family Life, takes its title and premise from Philip Larkin's poem which begins, "They fuck you up, your mum and dad/They may not mean to but they do."

This probing study of families is a societal analysis punctuated with examples of famously screwed-up individuals: Mia Farrow, John Hinckley who shot Ronald Reagan to impress actress Jodie Foster, and Michael Jackson.

His Guardian column last September analysing US president George W Bush's relationship with his parents makes worrying reading.

But during his two months in New Zealand -- then research around the world -- he is reverting to the premise of Britain on the Couch in which he interviewed middle-class Britons.

James, whose broad brow betrays no worry lines, is here to talk to their antipodean counterparts -- high achievers among them -- about their level of happiness. And if we are like the rest of the Western world, things might be miserable in the manicured, two-car, aspirational suburbs.

"I'm asking why is there this virus of always wanting what you haven't got, always wanting to be something you are not, and comparing yourself obsessively and enviously in terms of not just possessions but who you are. There is this greedy need for more and to be different - which seems to be making us unhappy."

Of course, he concedes, "happiness" is a loose term. Contentment or fulfillment are more apt descriptions.

"Happiness is not something I would recommend anybody even think about. I don't think we're put on this earth to be happy, it's ridiculous to expect to be happy. Happiness can be in one definition -- and I agree with this -- the short-term gratification of your physical and immediate needs, including your psycho-social needs. The little buzz of happiness from someone praising you, through to the happiness I am getting from smoking this cigarette.

"It's a temporary thing ... the best you can hope for is to be not unhappy."

Happiness, or whatever you call it, cannot be readily quantified, but mental illness and depression are measurable. And the rate, along with alcoholism and drug-dependency, is rising.

"New Zealanders will rightly look at this with a good deal of scepticism because one of the things I've found here is a healthy scepticism about this kind of talk," he laughs.

James has been here since mid-January, touring with his wife and two-year-old so he can put "the smell of the place on the page", and has now started researching and interviews.

From previous investigations into the malaise of what he has called "affluenza", he believes modern life does not meet two fundamental needs: status and attachment.

He notes the high divorce and separation rate which impacts on children, that society hasn't confronted the complex social changes as more women work outside the home, and that the elderly are isolated. All these have fragmented our sense of attachment to family and community.

"The nature of friendships has also changed. An awful lot of people are 'friends' with people upon whom they rely for help in their career. It's one thing to be engaged in office politics, but doing it getting drunk with friends or in bed with your wife is a toxic situation."

James also notes an epidemic of maladjusted social comparisons. Depressed people compare more. Mentally healthy people look to those who perform better and use it as a measure to improve themselves. Others feel humiliated by the comparison.

Even someone successful, famous and loved like Princess Diana was constantly comparing herself to others.

"So the goalposts are constantly moving. There is this obsessive and envious comparison - then you reach your goal so you create a new one. You can never arrive."

Worse, however, is the comparison downward when people look to those not performing as well - be it in golf or corporate politics - and feel depressed. They convince themselves the other person could beat them and be better if they had the same opportunities.

"That's the mentality you don't want to be in. But that is the mentality of modern life. So what's caused it?"

If pushed for a short answer he cites "Americanism". He has said "the closer a nation approximates to the American model of a highly advanced and technologically developed form of capitalism, the greater the rate of mental illness amongst its citizens".

Advanced capitalism has hijacked our finest aspirations, such as feminism's ideal of equal opportunity, which has turned into "women scratching each other's eyes out in order to be more successful and earn more money, and the total rejection of the role of the mother".

In his critique of the consumer capitalism which has created this, he considers four causes: the rise of individualism; the impact of television driving consumer greed and creating artificial expectations; the increased time children spend in school and pressure to succeed; and workplace changes.

In the instant-gratification world of Pop Idol shows -- a star created in the hermetically sealed context of television -- it seems logical to consider the role of the small box in the living room.

He cites the study of how shoplifting increased 5 per cent when television went beyond a 50 per cent penetration in each state in America. The more television people watch, the more materialistic their values become -- and they are likely to suffer from depression as a result.

But if we think there is an escape into an intellectual life, we are wrong. He believes much schooling today is destructive because of the pressures to succeed -- which will come as a surprise to parents who think schools don't push kids hard enough.

Even the successful become failures to themselves.

"I interviewed a 21-year-old girl who got the best first at Oxford University in English ever, in part one of her exams. But she was in a state of severe mental illness about the fact she might not get a best first ever in part two. What on earth is going on there? She had completely lost the plot, comparing herself to the whole history of people who have ever taken an English degree at Oxford."

And the workplace is even worse: we make ourselves into the person our bosses want, and in Britain chain stores like Marks and Spencers and Sainsbury's test employees to see if they have the right mix of assertion and humility. And they demand GCSE passes.

"Princess Diana and Fergie would not have been able to get a job in a department store. This is ludicrous and destructive to people."

The happiest people have an intrinsic interest in their work and are absorbed by it because it makes them happy. A local survey this week found 81 per cent of respondents think they are more productive at work if they have good relationships.

The obverse was that 39 per cent attributed pressures of work, exhaustion or work-related stress to the break-up of a relationship.

James is reluctant to speak of his findings in New Zealand, but observes we seem not to have been seduced by successive governments' attempts to drive us to embrace American-styled materialism. His early findings suggest we have avoided the virus of materialism which has taken root in Britain and the Unites States.

He has, however, encountered depression, and was stunned to learn while holidaying at Collingwood -- in picture-perfect Golden Bay with a catchment of some 2600 people -- that there had been four suicides.

In Auckland he has already encountered low and high grade depression among some successful interviewees, but says the scarcity of hard data here means it is difficult to assess accurately that nagging question: are we happy?

"I'm not sure you are doing badly in the happiness stakes, and maybe you are not as unhappy as you think you are. On an anecdotal level, your values are still intact, and I have found that in Auckland too."

Which should make us happy. Perhaps ...

post a comment