Graham Reid | | 36 min read

These first two articles published in the New Zealand Herald on consecutive weekends in December 2002, the first dealing with the background and problems of the Solomon Islands, and the second looking at possible avenues to peace and reconciliation. Five years on the police and military presence from Australia and New Zealand remains. Photographs are by Herald photographer Alan Gibson.

So this is where our clothes come to die. In the harbourside market of Honiara, the dusty and humid capital of the Solomon Islands, women squat beside meagre piles of peanuts, bananas and root vegetables wearing dirty, threadbare cast-offs from Sydney and Auckland.

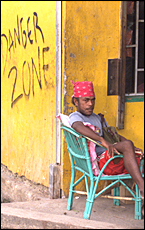

On the street old men wear filthy T-shirts with incongruous Nike and le Coq Sportif logos, a middle-aged man ducks through the traffic and fumes wearing a heavy overcoat in the 40C heat, and everywhere there are the menacing looking young guys hanging around in groups with Bob Marley and reggae dominating their clothing preference.

In Honiara - the town centre little more than a couple of hundred metres long and two dirty lanes deep - vendors wearing T-shirts from Australian universities or in once "smart-casual" shirts sit on low stools selling betel nut, single cigarettes and the dark, damp local tobacco rolled in pages from an exercise book.

This is a battered country dressed in last decade's cast-offs and living at subsistence level.

The red juice of betel nut stains the ground, rubbish is raked into high piles, lanes turn to mud after a tropical downpour and the few footpaths are frequently broken. Roads beyond Honiara are pitted with deep potholes and almost impassable. Fewer than 50km are paved in all the islands together.

In a doorway a young man, slightly drunk on 4.7 per cent SolBrew beer, is singing a Bob Marley anti-imperialism song, "We're gonna chase dem crazy baldheads outta town". Then he mutters his own coda directed at us, "Get outta the Solomons".

But it was a rare hostile comment in this place once known as "the Happy Isles".

For complex reasons - not least an inherited connection to this former British colony which achieved independence in '78 - New Zealand has a visible presence supplying key personnel as well as money.

There are nine New Zealand police advisers who, unarmed and without the power of arrest, are acting as frontline mentors for the local guys who are frequently reluctant to exercise their authority. "Wantok" - one talk, or a common culture - is the tradition and custom requires you help someone from your wantok, not a recipe for impartial policing. The Solomons also hit New Zealand headlines earlier this year when deputy high commissioner Bridget Nichols received a fatal stab wound (an Auckland coroner returned an open verdict). A fortnight ago a local man was sentenced to life imprisonment for the murder of ex-pat Kevin O'Brien on a Fletcher Construction site in February.

Behind the aid and assistance runs a deeper agenda. The Solomons are part of an arc of instability in this region which has edgy Bougainville and Papua New Guinea, combustible East Timor and fragmenting Indonesia to its north, all potentially volatile countries where the political systems are fragile or dysfunctional.

A fortnight ago a report prepared by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Beyond Bali, said unless Australia was prepared to become more involved, countries such as the Solomons could become run by criminals more than legitimate governments and provide a haven for hostile groups operating from bases there.

It is in everyone's best interests - not just those in this confluence of colliding Melanesian, Polynesian, Asian and European cultures - that the Solomons be stable, but according to the CIA World Factbook, "ethnic violence, government malfeasance and endemic crime have undermined stability and civil society". It is a failed state where gunmen recently ruled.

The Solomons, specifically Honiara on the island of Guadalcanal, ripped itself apart three years ago in what is euphemistically referred to as "the ethnic tensions" between those from Malaita Island living around Honiara and locals.

Malaitans have a reputation for being hardworking and are ambitious. Since World War II, when they came to Honiara to assist in the American war effort, many have risen to influence in business and politics. Some on Guadalcanal resented them for that. A bigger problem was land.

Sitting in the sweltering heat of his tidy, attractive and welcoming village near Malaita's main town of Auki, Henry explains: "On Malaita a boy inherits, but over there [on Guadalcanal] it goes to the girl. So when a Malaita boy marries a girl over there he gets land. Then maybe his brother comes to live with them and he marries, or an uncle who marries, and they get land, too."

Malaitans were inheriting Guadalcanal "kastom" (customary) land, some Guadalcanal locals objected and started to harass Malaitans.

Big mistake. Malaitans also have a reputation for being volatile and feisty. "Push one and two will push you back. Twice," says Henry with a laugh.

This is not to say they are unfriendly, you just don't mess with them. But some did and then the Malaitans fought back. The Malaitan Eagle Force was especially ruthless and effected a coup at gunpoint in 2000.

Since the Townsville Peace Agreement two years ago there has been a touchy truce and violence is becoming rare. Jimmy Rasta and his thugs may have quietened down, but you still can feel the tension.

The day we arrive the notorious Harold Keke - who didn't sign the TPA - has sent another policeman home for burial from the southeast of Guadalcanal where he is holed up. Keke is a messianic madman as much as rebel warlord and seems determined to hold out on the Weather Coast, named for its lousy climate. He or his supporters have killed almost a dozen police dispatched to arrest him.

Two days previous the Prime Minister's special adviser and local businessman Robert Goh was the target of an assassination attempt as he drove to a meeting in town.

But violence is now largely confined to those "special constables" created after the TPA who are ex-militants on the country's payroll. If the money is there. When it isn't - and it often isn't - they get tetchy. And in a country where the armoury is empty, they have an advantage. They have guns.

On the final day of our fortnight in the paradise which has been through hell, a few dozen disaffected special constables came to town for an angry rally. It is just another sign that undercurrents can surface with unpredictable rapidity and that the Solomons teeters on a political precipice.

A young man sadly says an Australian newspaper wrote bad things about the Solomons recently and that affected tourism. But aside from great diving in the Western Province, there's no tourism industry to speak of.

"Tell him to read the website," says Ian, an Australian back here to work for the first time since '98. "Same warning as Bali this place. Don't travel there unless you have to."

While Honiara is generally safe - there are no visible guns despite the occasional shots in the night - it is not a model of calm. Heather Riddell, our high commissioner, says she doesn't feel it is dangerous, but she is appropriately diplomatic: "The risks to expatriates are not excessive, although it is certainly an environment in which care needs to be taken, and we do advise people to be aware the situation can change."

Down at White River market, the advised limit of safe passage to the north of Honiara - a 10-minute mini-bus ride from the hub of Mendana Ave - the road runs out and a palpable sense of menace hangs heavy in the thick tropical air. Two guys make a point of standing on either side of me, not responding to a greeting, and accepting the offer of cigarettes without a spoken response. There is chill despite the humidity and it seems foolhardy to go further.

Back on Honiara's streets the young men who appear to be glowering behind wraparound shades brighten and respond to the standard "gudmoning" or "gud aftanun". Solomon Islanders are friendly, intelligent conversationalists and - given the paucity of political information available - well informed through the "coconut telegraph" of the machinations of politicians who are almost universally mistrusted. They live behind razor wire and are seldom to be found.

At parliament - an odd squat concrete bunker on the hill above town but with beautiful Melanesian designs inside - I am provided with a list of phone numbers for politicians, their permanent secretaries and press secretaries. It is worse than useless. The numbers either don't connect or no one answers.

For days I hear: "Your call cannot be completed at this time."

On the rare occasions when someone does answer I am often given another number. And the fruitless cycle begins again.

Government ministers aren't in their offices either. The few people who are faithfully take my business card and promise to call back. Not one does.

The following day I repeat the round of ministers' offices - most are careworn houses or prefabs. Many are closed, empty or staffed by different people today. I give up and go to the Point Cruz Yacht Club, a seafront bar favoured by locals, expat officials and rogue traders, entrepreneurs and cash-only businessmen.

"Politicians? They keep moving all the time," snorts Kenneth over a SolBrew. "A moving target is harder to hit."

New Zealand born Lloyd Powell, permanent secretary to the Minister of Finance Laurie Chan, says while that might sound dramatic there's an element of truth about it.

"It's not that they don't want to talk to you, it's just that we've all evolved a pattern of behaviour that rightly or wrongly we believe is prudent. I can't work in my office because there's a non-stop stream of people and the culture is you stand close to someone and watch. So that means you might have 20 people in your office and you cannot produce anything.

"Part of the role is to be seen, but I keep moving. People don't want to be near me, but we must continue to operate as if there's an element of normality. It's a very fine line. When I'm moving about and someone out of group comes at you, you have to make a judgment. Do they want you to sign something for them, or are they up to mischief?

"It's an interesting life and I'm getting quite good at peripheral vision."

Powell or his minister sign all the Governments cheques, around 300 a day. He signs three while we talk in the lobby of parliament.

"I've had guns poked at me and knives pulled on me and I am regularly invited to contemplate all manner of inducements that might suggest my pen comes out, and thus far I've avoided it. But you'd be pretty silly if you took it too lightly.

"Fundamentally we cannot run the ministry and no one has been able to. It's not possible when you are overrun by people pretty well every day. While local people have cheque-signing capabilities none are left alone at night, their wives and children and family are harassed.

"One guy was obliged to sign a cheque at 3 in the morning, when he was in hospital on a drip, at gunpoint. So I have withdrawn some of that. We get cabinet to set priorities and try to defend ourselves with the collective responsibility of cabinet.

"There are some very capable people here, contrary to what some might believe, but their ability to operate and contribute is enormously constrained by what is a complete breakdown in law, and that's not just in criminal behaviour."

The extent of high-level corruption makes a mockery of the country's motto, "To lead is to serve". Self-service has been the way of it.

Prime minister Sir Allan Kemakeza - who has links with the MEF - was dumped last year amid allegations of corruption. But in the fluidity of the Solomons' systems, where party loyalties are less relevant than aligning yourself with a person of influence, he is back - and promoted.

During "the tensions" big business pulled out, so now the country is broke. Civil servants often go unpaid for weeks, power and water supplies are erratic, and the credibility of the police is crippled from within because of the number of "special constables".

There is little confidence in the Government which is seen as endemically corrupt, irrelevant or out of touch. Parliament rarely sits - you can't have a vote of no-confidence if the house isn't sitting - and some cynically note the PM will have served a year, which entitles him to half salary as a pension for the rest of his life.

Noah sits at a plastic table in an airy, cool streetfront shop which sells drinks and sandwiches. The handwritten sign on the table says "Reserved for eat". He doesn't eat and the guy in the shirt emblazoned with "Security" ambles past leaving the many non-eaters unhindered. Noah is a carver from the Western Province who came to Honiara to see his three children.

"The government can't operate because it responds to all these pressure groups who put guns to their heads," he says wearily. "The whole thing is tainted with corruption. We need foreigners to come in and take charge."

What would he ask the Prime Minister if he could? "Why don't you just resign," he says with a shrug of his old shoulders.

It's Saturday when we arrive in Auki, the capital of Malaita. The mini-bus to town detours down the grass landing-strip to pick up abandoned beer bottles.

It's the morning after masked men have broken into a store on the main street. That they were armed indicates they were police from the nearby station where there are three police cars, not one with a full set of wheels. According to some, the store owner hadn't paid some rent, so the police took matters into their own hands and encouraged others to join the looting. Later we are told she is Chinese - as are many store and business owners in the Solomons - and was agitating with local politicians to be allowed to buy land.

Down at the market in the late afternoon a welcome, cool breeze is whipping through the now-deserted stalls. David bounces on a bulldozer and babbles incoherently. Clive shakes hands and explain there is no money for the mental institutions, so people like David wander aimlessly.

Clive's eyes are yellowed, his teeth red from betel nut and his hands and bare feet like gnarled, blackened oaks. He is fiftysomething at a guess and, like many, keen to talk politics. We start with the looting and he switches to the influence of Asians.

"They own the businesses," he says with quiet resentment, "and because they have supported this Government they expect favours in return. Like this woman here."

The PM's adviser who was shot at is Chinese, and the Minister of Finance is called Chan, he notes with a knowing nod. We hear this opinion often, but also that Solomon people are just as bad.

"Corruption is everywhere in Solomons," says Clive, "and the people are greedy.

"This market was kastom land but has been sold by politicians who keep the money for themselves."

That afternoon we fly back from Malaita in the dodgy looking eight-seater which splutters up the landing-strip with all the speed and commitment of an old motor scooter. Kids from the nearby village wave and Malaita spreads its tropical beauty below.

Thirty-five cramped minutes later we are back in Honiara, matted in sweat. At the Quality Motel the power has been off most of the day, but there is water for a shower.

The following day there is neither and the temperature arcs towards 40C.

I've been told if I'm at the office of the leader of the opposition, Patterson Oti, on Monday at 8am he will be there. I get there. He doesn't. His press secretary doesn't know where he is. He might not come here today, he might be in a meeting, he might go directly to parliament.

In the late afternoon I'm in the clean, empty restaurant of the motel which looks over the video store to the azure ocean beyond. One of the barboys, Philip, has gazed for hours out the window towards his home island of Florida. Another boy says he is saving the $S60 ($18) to go home to Malaita for Christmas.

They love their country but are sad for it. They just want peace. And things to work again.

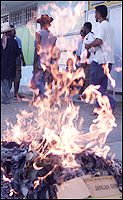

South African reggae singer Lucky Dube is on the tapedeck: "Dem don't build no schools anymore, dem don't build no 'ospitals anymore ... " In the alley below a woman lights a damp pile of leaves and plastic bottles, the acrid stench filtering through the window.

Somewhere in a Government office a phone rings and rings. "Your call cannot be completed at this time."

A rat runs across the window sill. In the alley two bored boys throw stones at a sleeping dog.

The power goes off again and an unsettling silence descends on the Happy Isles.

PART TWO: The Road to Salvation

When former militants from the Malaitan Eagle Force hijacked a vessel in Honiara harbour recently, a surprising thing happened.

"For the first time, and finally," Bob Pollard, a spokesman for the peace office of the Solomon Island Christian Association, sighs in exasperated relief, "the police moved against a militant group.

"Then the MEF guys signed this advert in the Solomon Star saying they wouldn't be threatened and if the police moved on them again there would be trouble.

"But they had to take out an ad in the Star," he hoots, "because they knew society had had a gutsful of them and that was the only way of getting their message out."

In the Solomons, where there is a palpable undercurrent of tension behind the smiling faces, this is a significant shift: the police acting like police. And being taken seriously.

But it's happening quite often now.

At the Solomon Star newspaper a few kilometres from central Honiara, one of the journalists, Robert, laughs about a recent incident. They published a photo of a car which had rolled into a ditch. No big deal.

Then a guy turned up at their office in unglamorous Chinatown claiming to be the vehicle's owner. He demanded $S1000 ($320) by way of compensation. He announced he was an ex-militant. That means he probably had a gun.

"We had no idea whether he was an ex-militant or not," says Robert, "but you don't want to take a chance. This sort of thing happens all the time, these ex-militant guys make threats and people have to give in because you just don't know what they might do."

This is the way of it in the Solomons where uncatalogued numbers of ex-militants are "special constables" and are still an unpredictable factor in the fluid politics of these beautiful, damaged Melanesian islands.

But Robert's story has a coda: "The guy hung around the office demanding his money, so we rang the police. When they came he ran off."

The journalists laugh. But the point is made again: the police came. A year ago, even six months ago, they simply wouldn't have turned up or, if they had, they would have done nothing.

Today these are small but significant barometers of a country coming to terms with the need to impose civil order.

Since the Townsville Peace Agreement in 2000 there has been an uneasy standoff between the Malaitan and Guadalcanal factions. Now there are signs of ordinary life returning: parliament is sitting again, police are on the street, people flocked to a soccer tournament with Papua New Guinea, and there was a beauty contest in the upmarket King Solomon Hotel.

But the Solomons' recovery is still on hold. The civil service is stacked with "ghost workers" who pull a salary but don't exist. Power and water supplies are erratic, and the reputation of the police is seriously compromised by the "special constables" problem.

Lindsay Duncan, who heads the small but visible New Zealand police contingent in Honiara, says that situation is being resolved through redundancies and a sense of order is returning. But local police lack resources and their systems are antiquated, if they exist at all.

"They sit and wait for people to come to them because they don't have vehicles and notebooks, so they can't go to the scene and if they did they couldn't take notes."

Duncan - who heads the team of 10 - is sitting in their cool offices in a shopping plaza at Panatina, a few minutes south of central Honiara. They are well provisioned with vehicles and computers provided by the International Police Monitoring Team funded by Australia and New Zealand. Their three-year commitment to the Solomons is a mentoring and guidance programme for local police.

Duncan spent six months in East Timor in 2000 and says the Solomons is better organised and has great potential.

"I can see that with a few years of peace and stability, and a bit of confidence in the security of the place, the businesses would come back. People have a good work ethic and it's a pleasure dealing with the locals who appreciate us being here."

The job hasn't been without its frustrations.

"There are a lot of things here where you think, 'It's so bloody obvious, why don't you do it?' But when you dig a bit deeper ... "

One problem is the reluctance of police to deal even-handedly with offenders. In a wantok society - one talk, or common culture - some are unwilling to arrest offenders from their wantok. And they are nervous about dealing with rowdy ex-pats.

Some are not politically neutral. In Tulagi Central Province the police commander was one of the nominees of a candidate in the recent provincial elections and senior police were openly campaigning.

There is no promotion on merit (it comes through wantok associations), and village constables operate in an undefined area between their authority and that of the chief.

The New Zealanders - five on the street, two working in CID on fraud cases - are the frontline of an $NZ8 million project. The Australians also have a presence in the middle tiers of policing and the justice system, and soon a British police commissioner will be appointed, all part of plan to restore credibility to a tarnished force.

The upper tier of society - the government - is equally tainted, mostly by accusations of corruption. Some progress is being made here, too, and the government, effectively broke and operating on half the income it had five years ago, is trying to put its house in order.

New Zealander Lloyd Powell, permanent secretary to the minister of finance, says he frequently feels like giving up and going home when faced with the complexity of the task.

"People here are enormously constrained by what is a complete breakdown in law, and that's not just in criminal behaviour. It's the recognition of a fiduciary duty as a member of a board, the concept that people won't forge my signature, that they won't get their relatives to break into the computer system to produce cheques in the middle of the night and arrange for them to be signed by other people.

"I sign every one and attempt to have an understanding of every cheque that is signed. If you think about that, it's a lunatic task but it's the best we can do."

Not one cheque has bounced since he started in the job in May 2000 "and the year prior to that one bank made half a million dollars in bad cheque fees".

"We are trying to pattern people into the certainty that if cabinet says it will be paid and the cash flow is available no cheque will bounce. In itself that's an achievement, however small.

"In terms of true and fair accounting this country hasn't had a clean set since 1984, hasn't had audited ones presented between '96 and '99. Foreign capital will tolerate a lot, but not arbitrary decisions. That's what happens here. But bankable projects have to conform to the club rules."

One of the clubs prepared to pump big money into these scattered islands is the European Union which has around ?6.7 million (NZ$13.3 million) ready to be released, most aimed at rural development. But it is contingent on social stability, transparency in government and clean accounts.

"It is in a bank account in Europe where it is earning interest," says Hendrik Smets, the commission's resident adviser.

"If the government survives this parliamentary session and the budget is accepted then I am optimistic. If that doesn't happen then I cannot be.

"You don't feel they are in an emergency situation because they speak in the long term. This is a country in an emergency situation - but everybody speaks about the sex of the angels," he says with a Gallic shrug.

Yves Gillet, from the commission's rural development and fisheries unit, agrees the situation is serious which is why donors have spoken with one voice to influence the government to make the necessary reforms. And quickly.

"When you have a nearly dead body you have take immediate measures to resuscitate it . Then in the medium term you can look at how to have a complete recovery. But first you have to do the emergency curing."

Federal reform and offering a measure of autonomy to the provinces, which is part of an inquiry by the United Nations Development Programme, may not be the answer either. That could simply create a schism between have and have-not provinces. But political reform of some kind seems essential in a country where two systems overlap: wantok and the inherited Westminster parliamentary system.

In wantok the "bigman" bestows gifts and influence. Where once this came from tribal authority it is now seeded by political position, which leads to high-level corruption.

But while constitutional reform would be welcomed by many, others say the priority is dealing with the grievances of the recent past.

Pollard, of SICA, is one of many who have suggested a Truth and Reconciliation Committee to hear the stories of victims during the ethnic tensions, some of whom have received meagre cash compensations for loss of family or land.

"We're living in society now where there is a lot of collective guilt, where the people are really brassed off with Malaitans. A truth commission would help clear that up, that it's not 'Malaitans', it's this individual or these groups of people. If we don't do it we'll pay a higher price.

"Let's look at what happened from the victims' perspective and get away from chequebook diplomacy. All that has done is fuel the militants and kept them in power. A truth process would enable some sort of genuine reconciliation. There is a strong propensity here to forgive and the stories would enable us to get our national unity together."

SICA has produced 10,000 booklets outlining its proposal and Pollard says politicians would be unwise to ignore this association of the five main churches which has 90 per cent of the population affiliated to one or other.

"The commission should also have the power to investigate things like the killings in the hospital. The guys shot people in the beds. People know who did that and as a society that has to be dealt with.

"Even the militants have a story to be told and many want their names cleared. I also don't think they have the capacity now to be troublemakers," he says, citing the MEF being reduced to advertising in the newspaper.

Others dismiss a Truth and Reconciliation Committee as an intellectual nicety. The say people just want to work and get on with their lives. But the reality is the country is bankrupt and dependent on outside aid.

Jennifer Poole, a World Vision programme manager, says introducing resources into a resource-scarce environment can create tensions so care must be taken. World Vision has village projects which occupy youth and give them marketable skills but is finding it increasingly hard to keep up the sponsorship.

"It has been challenging to find sponsors for kids in the Pacific. They are absolutely gorgeous and they look all chubby and happy. But the other reason is the media focus on the desperate plight in Ethiopia and Afghanistan which really needs immediate attention. No one here is actually starving.

"People here are helpful, great to work with, and want to get things done. I don't think this place is going to hell in handbasket. There are a lot of dedicated people trying to make it get better. The country has potential, it's just got no money.

"It is chronically undereducated, however, and that makes it hard because many can't run a functional business. We need to give them those skills."

Upstairs from her modest office is a man doing just that. With an annual budget of $S30,000 ($10,000) provided by the New Zealand government, Andrew Sale manages the Small Business Enterprise Centre which provides four week-long courses in business training. Each costs $S150.

"The fact they are prepared to spend that shows they are serious. We have an accountant in the office who will do the books for those who have been on the courses cheaper than elsewhere. But we have the attitude nothing is free and we don't entertain that attitude. This is business and we have to teach that and conduct ourselves in that way."

On this week his courses are full with redundant civil servants looking to change their careers. The centre invites successful business people to speak - the Chinese keep to themselves and don't want to share their secrets, he says - and they are helpful in telling people how to negotiate their way around wantok.

"Wantok is our safety net but some people abuse it. People in villages come to Honiara and take advantage to the point where it may kill a small business."

As with policing and aid programmes, this is bottom-up progress. There are healthy signs: the People First Network (Pfnet) is gradually getting the information highway into small villages in a country where there are few passable roads. Powell, in the finance ministry, says small businesses are growing and international investors are slowly coming back.

The natural resources didn't vanish during the tensions and fisheries have enormous potential. A national network has been established to share and save seeds for crops; the Taiwanese are involved in logging and made a US$65,000 ($125,900) contribution to a hydro scheme; the Japanese government has committed to the development of Honiara's Henderson Airport; Australian money is building roads; New Zealand dollars go into policing and aid projects.

Big money-earners, such as the Gold Rich Mine, which was abandoned during the tensions, haven't yet re-opened. Powell says it is more important to establish a climate of good business practice and get other things moving.

There are reservations that "white-guy money" is becoming the expectation and the Solomons is becoming too aid-dependent.

"There's a sense here among some," says an aid worker who wouldn't be named, "that if you just leave it, white-guy money will arrive to take care of things."

But for sponsors, the European Commission, the government and people on the street the priorities are simple: law and order, and rooting out corruption. Even the recent beauty queen competition was plagued by suggestions of a jack-up.

IT IS mid-afternoon in Honiara's listless market. People mill around, the women all sell much the same thing: peanuts, vegetables, pineapples. In a corner the bad boys are playing over-and-unders with dice at 50 cents a throw.

I buy 10 sweet bananas for $S2 (70 cents) and sit. In less than a minute David comes up and shakes my hand.

"We are very tired of the fighting now," he says. "Solomons people are very friendly, very nice. But it is hard here now. We will be all right, but we need help."

I think of what Mark, a Telecom worker, told me. He wouldn't turn his computer off because it would rust. You could almost see the rust growing on it, he said.

It seemed an emblem for this country struggling with its past, moving to an uncertain future, and so dependent on outside assistance. In its absence, it might turn to rust.

THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES RAN AS EVENTS UNFOLDED IN THE SOLOMONS OVER THE NEXT FEW MONTHS.

January 3 2003

From the comfort of this distance the problem had a simple solution: Cyclone Zoe with winds of around 300km/h had battered remote Tikopia, Fataka and Anuta islands in the Solomons some 1000km from the capital Honiara.

The obvious and immediate thing to do was to send a boat laden with food and medical supplies.

But in the Solomon Islands things are never quite that simple.

As Lindsay Duncan, head of the New Zealand police contingent in Honiara recently told the Herald: "There are a lot of things here where you think, 'It's bloody obvious, why don't you do it?' But when you dig a bit deeper ... "

In this case the boat wasn't going anywhere because the Government couldn't pay for the $50,000 emergency aid of rice and tinned food. It also couldn't pay a similar amount for the fuel although the Australian Government stepped in to stump up that money.

But while many have waited an anxious week since the cyclone levelled 5sq km Tikopia Island, where it is believed between 1300 and 2000 people live, the boat remained tied up at Honiara's wharf.

That may appear tragically inept, but such impotence is common in the Solomons.

Duncan cites the condition of the holding cells in central police station.

They are appalling. You smell them before you see them and when you walk down the dark and narrow brick corridor you are confronted with human excrement and walls turned brown with age, neglect and accumulated filth. The air is thick and fetid and leaves you choking.

The simple solution is to hose the place out. Or at least get a bucket and a mop.

"But when you dig a bit deeper ... "

The station has no plumbing so the police have to pay the Fire Service to sluice the cells out. But the Fire Service has no fuel to get there so the police have to not only find money for that, but also find the petrol.

That isn't easy either. It can be in short supply.

With an arbitrary power supply - because the Government can't pay the electricity department - some businesses and Government departments have generators, but the shortage of fuel can render them ineffective also.

This is a country where simple problems can be very complex.

This has been the way in the Solomons since the ethnic tensions between Malaitan people living on Guadalcanal Island fought back against harassment from the local "Guale".

Militants on both sides armed themselves and Guadalcanal became a war zone in 1999. Thousands of Malaitans fled back to their home island, a mere 50km away. Hundreds of Malaitans and Guale lost their lives in a ruthless conflict which included beheadings and torture, and it was only when the Malaitan Eagle Force deposed the Prime Minister at gunpoint that neighbouring countries demanded a cessation to the violence. The Townsville Peace Agreement has lessened the violence but today the Solomons is a bankrupt nation where the politics are fragile and the people are trying to adopt some semblance of normal life again.

The civil infrastructure has crumbled because the Government is stacked with "ghost workers" and those who actually exist often cannot be paid. Before the patrol boat Auki finally left Honiara there were demands from its police crew for extra pay.

Power and water supplies are erratic, and international businesses such as the Gold Ridge mine were destroyed or their owners fled during "the tensions". While no one is actually starving in these fruitfully tropical islands there is only subsistence living for many in the 4000 villages scattered around almost 1000 islands in the archipelago. The Solomon Islands is a failed state with no money to help itself.

Lloyd Powell, a New Zealander who is Permanent Secretary to the Minister of Finance, is blunt but pragmatic: "This country had run consistently on an income of $400 million and we're now running in the area of about $250 million - so the reality is you have to learn to live on that.

"The economy is growing marginally and the indicators are that there is a tentative, sensitive turnaround. People are inquiring about shop space, traders are coming in and the resources of sea and land are still there.

"The biggest time bomb is population growth and we have to grow the economy at the same pace to stop people drifting into towns."

There is money available to the Solomons, and extremely large amounts. The European Commission is prepared to release millions of dollars - US$7.8 million ($14.9 million) is sitting in an emergency fund - if it can be satisfied there is good governance and transparency.

But in a country where the rule of law can be loosely interpreted and corruption is rife (often not seen as corruption but the cultural norm for powerful people to help their own) these two conditions are difficult to satisfy.

"The priorities of the Government therefore are law and order," says Powell, "and health and education, and doing what it can to support a private sector for a provincial economic recovery."

While these goals of the medium and long term are admirable the EC representatives insist the Solomons is in crisis right now and immediate reforms are necessary. That might include constitutional changes.

But none of this is going to get a ship full of supplies to the cyclone-battered zone in the far southeast of the sprawling Solomons.

That demands immediate action from individuals prepared to be held responsible.

Right now in this country where 98 per cent of the population is Christian and many are very devout, most politicians will be back in their home provinces - many quite literally out of contact - for Christmas and New Year.

And so the boat remained tied up at the dock.

post a comment