Graham Reid | | 7 min read

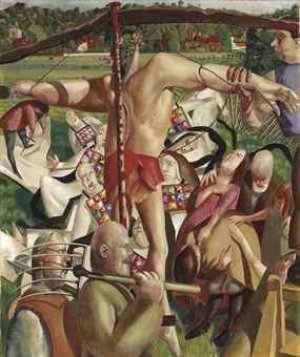

Sex fascinated Stanley Spencer. But so did angels, the transcendence of the spirit through faith, and life in his home village of Cookham where, as a child, he believed biblical events had taken place and been witnessed by local folk.

This confluence of religious and rural influences, and his belief that sexual and spiritual desire were entwined, were resolved in an intellectually energised art as distinctive as it was different.

Sir Stanley Spencer - knighted in 1958, the year before his death - was one of the greatest English painters of the past century. And few were more English. He located biblical stories in Cookham. Typically his Resurrection completed in 1926 takes place in its churchyard with the nearby Thames as the River Styx and holidaymakers on it as spirits of the departed.

In an art world which often thrives on moodiness and introspection, his paintings frequently dance with a celebration of the ordinariness of life as they illuminate the extraordinary spiritual world.

"When I was young about the village as a child," he said, "I was aware of a wonderful something which was everywhere to be felt, it was bang all around me, it was heaven as clear as the Cookham day."

Spencer's work wasn't always highly regarded. He was called "the divine fool of British art" and one critic wrote, "It is fair to say that Spencer's work was divided into two distinct categories - comical versions of events and intense realism."

As with most glib assessments it was far from the truth.

Spencer drew from Giotto and in his religiosity was an inheritor of the Pre-Raphaelite school, yet his idiosyncratic and visionary works betray the hand of a true avant-garde artist and in 1919 critic Roger Fry included Spencer in an exhibition alongside Picasso, Modigliani and Cezanne.

Curiously for a painter who is no less driven by a personal vision than Blake or Chagall, his work remains less well known and only belatedly sought after by international collectors and galleries. In part that is because British art, at least from the American perspective which dominated markets and criticism since the middle of last century, has been characterised as provincial and lacking in the grand sweep or genre-defining philosophical thrust.

In part that is because British art, at least from the American perspective which dominated markets and criticism since the middle of last century, has been characterised as provincial and lacking in the grand sweep or genre-defining philosophical thrust.

With the exception of Vorticism - that peculiarly English movement which welded together Cubism, Futurism and Wyndham Lewis' singular personality - British art in the 20th century was identified by individuals rather than stylistic shifts, unlike American art where critics and a fashion-conscious market could latch on to the shorthand.

Spencer belonged to no school and invited few followers. With no advance guard of PR trumpeting his genius, or train of yapping acolytes behind, Spencer has been problematic. He was eccentric (he carried his old shopping bag to Buckingham Palace when going to be knighted), disliked art theory, and felt in his immediate world a sense of the greatness beyond.

There is no crib-sheet into Spencer, just a lot of pleasure to be had in his work.

Spencer often spoke of there being two of him existing simultaneously in separate lives: one was his "down-to-earth" life and the other his "up-in-heaven" life. As his biographer Kenneth Pople notes, current understandings of the word "heaven" often drip with sentimentality which are not what Spencer meant: "Today's reader might feel more comfortable with a secular phrase such as 'extended reality'," writes Pople.

More prosaically Spencer said, "I am on the side of the angels and dirt."

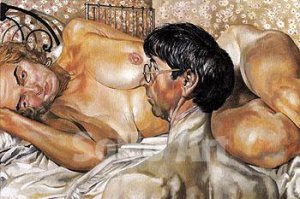

Much of his art is an attempt to resolve that duality. It is also often about sex.

At core his work employed a private mythology which came from the childhood imprinting which was either reinforced or challenged by his subsequent life. Spencer was born into a well-to-do family in June 1891, the eighth surviving child of a piano teacher and his wife. He enjoyed the rituals in the church and his father's reading of the Bible, and was educated at a school run by two of his sisters in their small village in Berkshire. There he read the Bible, Bunyan and Milton, enjoyed music and in his mid teens attended Maidenhead Technical College where he trained as an artist before going to Slade School of Art for five years. There he was nicknamed "Cookham" because of his love for the village to which he returned every night.

Spencer was born into a well-to-do family in June 1891, the eighth surviving child of a piano teacher and his wife. He enjoyed the rituals in the church and his father's reading of the Bible, and was educated at a school run by two of his sisters in their small village in Berkshire. There he read the Bible, Bunyan and Milton, enjoyed music and in his mid teens attended Maidenhead Technical College where he trained as an artist before going to Slade School of Art for five years. There he was nicknamed "Cookham" because of his love for the village to which he returned every night.

In his early Twenties he returned to Cookham and painted, but a year into World War I enlisted in the medical corp and saw out the final years in field ambulance divisions and the infantry.

He returned to Cookham, painted the official war picture Travoys with Wounded Soldiers (now in the Imperial Army Museum), then was commissioned to paint an ambitious series of murals depicting army life for the Sandham Memorial Chapel at Burghclere in Hampshire, now widely considered one of the great works of English painting last century and a modern parallel to Giotto's work in the Arena Chapel in Padua.

In 1922 he visited Yugoslavia on a painting holiday with the Carline family and three years later married daughter Hilda. He was in his 30s and a virgin, but the joy he discovered in the marriage bed liberated him from his Victorianism and fuelled a celebration of blissful, almost religious, sexuality which informed his life. He came to believe in free sexuality and many of his works have an undisguised erotic and exultant quality.

His eroticism got him into trouble. In 1950 the outgoing Royal Academy president, Sir Alfred Munnings, initiated a police prosecution against Spencer for alleged obscenity.

He painted interiors and private chapels and exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 1932 and 1938. In 1935 he resigned from the Royal Academy, when it rejected two of his works. His private life wasn't without controversy, either. In 1937 Hilda divorced him but four days later he married a friend, Patricia Preese, the lesbian lover of sculptor Dorothy Hepworth. The marriage was not consummated but she did move in with him, then kicked him out. In intense portraits of the exploitative Preese - with whom he had long been obsessed - her intense gaze is cold and unflinching. One of his nude portraits of her was equally emotionally raw and was not exhibited in his lifetime.

His private life wasn't without controversy, either. In 1937 Hilda divorced him but four days later he married a friend, Patricia Preese, the lesbian lover of sculptor Dorothy Hepworth. The marriage was not consummated but she did move in with him, then kicked him out. In intense portraits of the exploitative Preese - with whom he had long been obsessed - her intense gaze is cold and unflinching. One of his nude portraits of her was equally emotionally raw and was not exhibited in his lifetime.

In 1938 he lived a hermit-like but happy existence in Swiss Cottage where he envisioned a series of 40 canvases along the theme of Christ in the wilderness (eight were completed).

Over the next decade he was in demand for commissions (as an official war artist during World War II he painted shipbuilding at Clyde) but mostly lived in Cookham. He visited China as part of a cultural delegation in 1954 and was honoured with a retrospective at the Tate in 1955.

In the past two decades Spencer's work has undergone a rediscovery. In 1980 there was a major exhibition at the Royal Academy, another in Washington in 1997, and the following year Christie's held an important and successful sale of 3000 of his drawings and memorabilia from his daughters' collection which fetched high prices.

British public galleries have been buying his works when they come on the market, and two years ago the Tate Britain mounted a popular retrospective which had critics clucking appreciatively. His wider recognition and rehabilitation had arrived.

In 1962 the Stanley Spencer Gallery opened in the old chapel in Cookham where he worshipped as a child. It was around these streets the tiny figure of Spencer - only 1.57m - carried his easel in an old pram and painted its spires, people and the river.

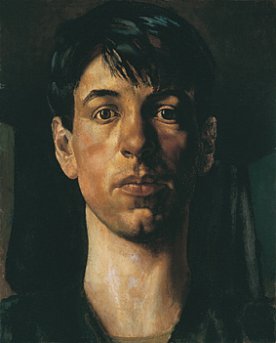

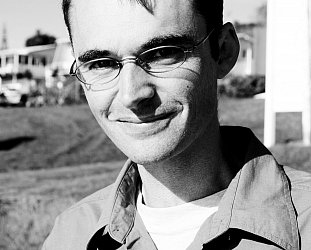

Spencer is not a difficult artist to enjoy or be informed by. Some might smirk that sometimes his figurative work seems close to Beryl Cook. But while his singular Self Portrait of 1914 in this collection contains elements of a distant knowingness and intellectual bewilderment - he could have been in any introspective Flying Nun band in the early 80s - much of his other work often has a joyous, celebratory quality. That seems to have been the man.

On the night he died in December 1959 he was visibly tired and the friend with him suggested he leave Spencer to himself. Unable to speak, the artist, who said he had been visited by angels, took up a pen and wrote, "I am never weary, never bored. Why should you think I am. Sadness and sorrow is not me."

post a comment