Graham Reid | | 7 min read

Dan Brown's Vatican-based thriller Angels and Demons typically raises lots of questions: notably why would you buy the book now when you can just go see the movie?

But to give Brown his due, he writes a cracking story which in the film fairly belts along -- and has as its backdrop the arcane mysteries of a Papal Conclave, the time when old red-frocked cardinals get behind locked doors and choose a new pope.

Brown's story comes with all the 21st century trappings -- high tech, the whole science V religion debate, a hired killer, squealing tyres and a car bomb, mad Catholics and handsome Italian policemen -- but as is so often the case, fiction is a poor substitute for reality. And there have been some pretty awkward conclaves in the past.

On one occasion the people waiting outside the new palace in Viterbo, north of Rome, grew impatient. This conclave was dragging on too long.

Behind the walls 15 cardinals were trying to choose a new pope, but the conclave was divided into French and Italian factions, neither able to wrestle the necessary two-thirds majority.

As the throne of St Peter remained vacant, drastic measures became necessary to hurry along God's decision-makers. First the cardinals' food rations were curtailed, then portions of the palazzo's roof removed so the vagaries of the weather might beat down urgency upon the wise heads inside.

Finally a compromise was brokered and Theobald Visconti, archdeacon of Liege, was chosen as the new Pope.

It was 1271 and, until his consecration as Pope Gregory X on March 27, the papacy had been vacant for almost three years, the longest conclave of cardinals in history.

In modern times conclaves have reached a result with mercifully more haste, but for the outside world the result has been no less anticipated.

These days attention traditionally centres on a chimney near the Sistine Chapel from which the smoke of burning ballot papers relays the result. White smoke means the new Pope has been chosen, black smoke means the waiting must go on.

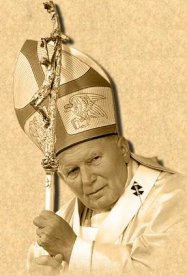

When a pope is frail -- as happened with Pope John Paul II -- subtle preparations are made as cardinals discreetly look among themselves at the candidates for succession. The Guardian noted however in 2001, four years before the death of Pope John Paul II, "As death-watches go, the Vatican is more subtle than most. No cabals huddle in marble corridors discussing tactics. There is no rubber-chicken circuit. Yet, subterranean and imperceptible, the campaigning is under way."

Bishops gossip but "it's always been a rule there should not be lobbying", New Zealand's Cardinal Tom Williams, Archbishop of Wellington told me in 2001.

"To the best of my knowledge there's no canvassing for votes and no lobbying for preferred candidates. But human nature being what it is ... However, there are no nominations and putting forward the merits of each one as in a caucus."

Changes to the nature of the conclave in 2001 made an always unpredictable election after Pope John Paul II's death even more difficult to read.

In February that year, he elevated another 44 as princes of the Catholic Church, so expanding the College of Cardinals to 185, the largest it had been. Of those, 133 were younger than 80 and so eligible to vote for the next pope.

All adult Catholic males are eligible for the position of pope, but it is highly likely, possibly even certain, that he who next holds the keys to the Kingdom will be drawn from among the cardinals.

Today this large group includes representatives of the diverse opinions within the Catholic Church, from liberals to conservatives, from old-world European white to politicised African black. And vice-versa.

But what was significant about the recently elevated 44 was that 11 were from Latin America. Currently 20 per cent of cardinals are Latin American, making this the biggest voting bloc within the conclave. Italians, traditionally the largest single group, make up slightly less than 18 per cent.

But while such a change reflected the Church's contemporary demographic, it was not necessarily relevant within a conclave, said Williams.

"Conclaves are simply not possible to read from that point of view. I could do analysis on the basis of country of origin, the kind of work the cardinals have been engaged in, I could think of their ages and theological positions -- and I'd be quite sure to get nowhere near the answer."

Observers of the papacy however noted the college had become incrementally more conservative in recent decades. More than 85 per cent of the cardinals were appointed by Pope John Paul II, who had barred nuns and priests from work with gays and lesbians, published edicts against birth control, been firmly against women priests and abortion, and had held the line on remarriage after divorce and celibacy in the priesthood.

Archaic as all that may sound in the 21st century, he was doing exactly what any Catholic would do in his position, said Father Thomas Reese, editor of the US Catholic weekly America. "As a result, although there may be differences in styles and personalities, there will be continuity between him and the next Pope."

Again, not necessarily so, said Williams. It's one thing to pick bishops and then from their ranks cardinals, but to assume they wouldn't change their opinions over time would be a mistake.

Many note that John Paul II was perceived as a moderate but was latterly characterised in many circles as a conservative.

John Paul II is already seen as a historic Pope. He was unique in that he came from Eastern Europe - he was born Karol Wojtyla, in Wadowice, Poland - and grew up in the crucible of 20th century politics of Nazism, communism and the Holocaust. He ascended to the throne of St Peter and witnessed the dissolution of the socialist republics. He was a modern European man in that he possesses a remarkable facility with language.

Through that - and his understanding of media-genic gestures such as the kissing of tarmacs - he communicated on a global level. When he became Pope he was 58, physically tough, looked like a lock forward and was a keen downhill skier. He survived an assassination attempt in St Peter's Square in 1981 and, despite his deteriorating condition, was perceived as morally strong.

And he was a potent symbol of the papacy. His power often lay not in what he said but in his sheer presence.

His symbolic forgiveness of the man who tried to assassinate him resonated on a human level, and his papacy was been characterised by his constant travel, important political gestures (his visit to a synagogue in Rome, letters to US President George Bush sen and Iraq's Saddam Hussein in an effort to stop the Gulf War) and acts of simple human kindness. He went to Auschwitz and Hiroshima, met Fidel Castro, Princess Diana, George W. Bush and most other political leaders, and conspicuously (forgivably even) nodded off in a recent Bob Dylan concert.

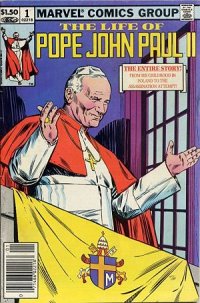

There was even a Marvel comic about his life.

There was even a Marvel comic about his life.

By virtue of circumstance, he presided over the 2000 jubilee year and, like it or not, his conservatism effectively denounced and curtailed important Liberation Theology movements (Marxism meets Catholicism) in South America.

He also canonised more than 300 saints and was responsible for the first rewrite of the Catholic catechism in more than 300 years.

Britain's New Statesman called him "a spiritual Superman" and he possesses enormous personal charisma. Unlike his successor, he was a crowd-puller.

This despite being greeted with "Chi e?" (Who's he?) by the expectant crowd in St Peter's Square.

With the expanded College of Cardinals, the church today wil have plenty of candidates to choose from when it comes to choosing another pope. However that large, and some have suggested unwieldy, number of cardinals may make for a protracted, and perhaps even deadlocked, conclave.

And no one wants another roof-razing Viterbo.

To mitigate against that possibility, in 1996 John Paul II changed the conclave rules for the necessary majority. For the first 12 or 13 days the winner must have the traditional two-thirds plus one vote (the one to account for candidates who vote for themselves), but after that the conclave can choose to adopt a simple majority rule.

And all the while the world will wait for the ritual of the smoke signals, an emblem of how little Catholic traditions change in the face of modern life.

But how do these elderly gentlemen from far-flung corners of the planet, each seeing the disparate Catholic world from their own vantage point, know who to vote for?

Williams told me they will have met many of their peers previously and the "sixth extraordinary consistory" in May 2001 in Rome -- 155 international cardinals called together by the Pope, ostensibly to map out prospects for the church in the third millennium -- was widely characterised as a pre-conclave before the ineitable death of John Paul II.

"I got no impression of that, however," said Williams, "but it was certainly an opportunity to meet the new ones. That's how we form our impressions, and from reading articles and reviews.

"You do your homework. I have a couple of books with photos of cardinals and their biographies and something by them in their own words and what they stand for."

Some candidates will always be immediately excluded by virtue of personality or ethical persuasion. But any new pope will need to be a scholar steeped in the history of the church, and a man of this complex era. John Paul II, as a frequent flyer for the faith, set the expectation of a Pope being a universal pastor prepared to be a travelling salesman.

A 21st century pope needs to be media-conscious and possess a world view, and be able to bridge the gap between Europe (where the church is on the decline) and the growth regions of South America and Africa.

He will have to face the rise of dangerous religious fundamentalism of all kinds, and now intolerance driven by the rise of militant Islam. It might be useful if he spoke Arabic.

At a more prosaic level, age is also an issue. If the conclave doesn't want to repeat the two-decade reign of John Paul II -- longer than all but five of his 264 predecessors -- the relative youth of frontrunners might work against them.

There are also geo-political considerations -- but the adage will probably remain true: he who enters the conclave as the next pope will come out as a cardinal.

The wisdom or otherwise of bookies and pope-makers can be confounded by something that the secular world conspicuously fails to consider. No speculation can take into account divine intervention.

When the whole of the conclave, after prayer and contemplation, is moved to support one particular person by acclamation, that would be regarded as the body being divinely inspired.

And that is something beyond the comprehension of mortal man.

Only one thing is certain.

Regardless of how long the cardinals take, no one is going to suggest removing the roof of the Sistine Chapel to hurry them along.

post a comment