Graham Reid | | 9 min read

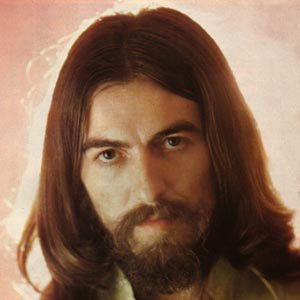

"Nothing in this life that I've been trying, can equal or surpass the art of dying"

-- Art of Dying by George Harrison, 1970

When the late George Harrison wrote Art of Dying for his first post-Beatles album All Things Must Pass he was only 27 and his final days were some 30 years away. Yet from his mid-20s when he began embracing Krishna-consciousness he repeatedly, in music and interviews, spoke of the inevitability of death and, because of its certainty and his faith, he faced it without fear.

Quite what he thought in his final moments we will never know, but Harrison prepared meticulously for his final days. He retreated to the secure home of a friend in California to avoid a media frenzy at his English estate, and brought in spiritual advisers to be with him and his family.

He made arrangements for his cremation and the disposal of his ashes. It was an orderly, managed, dignified and private departure from this life.

Confronting death so openly, even fearlessly, is now not uncommon.

In 2001 former New Zealand television newsreader Angela D'Audney went public with the brain tumour she knows is going to kill her and co-wrote her autobiography, Angela: A Wonderful Life! with the New Zealand Woman's Weekly deputy editor Nicky Pellegrino.

Sociologist Tracey McIntosh who teaches issues of death and dying at the University of Auckland uses the phrase "impression management" to describe such behaviour. Because we have increasingly gained control over our world we also try to manage death. For many people, she says, the way they deal with death conforms to the personal narrative of their lives.

Sinclair, a private man, wrote about simple pleasures and reminisced on life, but revealed little of his own history. D'Audney wrote a book which placed herself at the centre of the screen and reduced others to bit players.

Once, funerals were the place for accolades and tributes to the deceased. Today, some people try to predetermine how they will be remembered and hear the acclaim before their death.

In the case of celebrities, the cynical might suggest those who have lived in the spotlight are loathe to leave it and so choreograph their passing with self-aggrandisement. But it is clearly more than that.

We are curious about death, and how others deal with it. Their actions might offer clues as to how we can cope or mediate our way through its difficulties. And there's such a lot of death about we'd be less than human if we were indifferent to it. We may be engaged by life, but death lasts longer.

Pellegrino on D'Audney: "It is very important for her to have a Jewish funeral and she's taken some of her non-Jewish friends to synagogue. But even while preparing for her funeral she was still coming to terms with what was happening to her. It was almost part of the process of realising what was happening and accepting it. Doing the book was as well."

Earlier this month in the New Zealand Woman's Weekly actress Pam Ferris, who plays Ma Larkin in The Darling Buds of May, spoke about people making a "living will" in which they can stipulate that they not be kept alive beyond the point they would normally have slipped away. In other words, controlling events in the departure lounge.

But illness and the attrition of life functions may be a good thing. The 16th-century philosopher Michel de Montaigne noted when unwell he was less likely to cling to life and "I come to view death with much less frightened eyes. This makes me hope that the farther I get from life and the nearer to death, the more easily I shall accept the exchange."

McIntosh speaks of "the gift of cancer" which often allows its victims time to better prepare for their death. While people might fear cancer, when questioned they will say they'd prefer time to prepare rather than being bowled by a bus. For those left behind it is easier to reconcile one than the other.

Pellegrino on D'Audney again: "For her the important thing was she should be able to stay at home and [it be] a peaceful end. The worst thing she could imagine would be to die in a fiery car crash."

When death occurs is also significant in how we see it. Who had the "better" death: General Patton (despite being fatally injured in a traffic accident) dying at aged 60 after a successful military career; or poet Wilfred Owen dying aged 25 a week before the end of the First World War?

The conundrum is, if we have a clear notion of what is a good life then why can we not define a good death? For most it probably means no pain, time to put our affairs in order and acceptance. "And also a sense others have appreciated your life," says McIntosh.

Many of us want death with dignity and on our own terms, although those conditions may change. McIntosh observes young people will say they want to die in their sleep because it is peaceful, but older people say that's not a good death because you aren't conscious of it.

And do we go gentle into that good night? Or as Dylan Thomas suggested rage, rage against the dying of the light?

Either way won't do you much good. It'll get you regardless.

Perhaps what troubles us most is not the realisation of the generality of death -- only Peter Pan or those in serious denial would pretend otherwise -- but by the singularity of a death. When someone we know dies, or we are faced with death ourselves, then our perception changes.

We are surrounded by death, but they are atypical deaths: a murder in the suburbs where a robbery went wrong, some celebrities in a plane crash, dozens wiped out by molten lava ...

And we rationalise how and where deaths occur.

McIntosh: "When something like September 11 happens you realise the way we normalise certain forms of death. One of the first things I saw was a woman saying she couldn't believe it was happening in New York. Beirut, yes, but not New York."

That 2400 people died in a tidal wave in Papua New Guinea went largely unheralded compared with the grievance over September 11 illustrates also that some deaths -- Diana, Princess of Wales is the most obvious -- are considered more valuable than others.

Mundane death isn't newsworthy although death and dying have become the lifeblood of talk television and the publishing industry.

After Elisabeth Kubler-Ross' breakthrough book On Death and Dying in 1969, in which she identified a series of stages people commonly go through after being diagnosed with a terminal illness, there was a liberation in talking and writing about death. Death and bereavement became processes to work through and there are now thousands of books on how to cope with death -- yours or that of someone close to you.

But the slight book was also about the art of dying which explained its success. "I'm on the last great journey," Schwartz told Albom. "People want me to tell them what to pack."

And why not make preparations? We are often judged by our end and a bad death can negate a good life. As DeQuincey observed: "If a man dies by some sudden death when he happens to be intoxicated, such a death is falsely regarded with a particular horror; as though the intoxication were suddenly exalted into blasphemy ... if his intoxication were a solitary accident there can be no reason for allowing special emphasis to this act simply because through misfortune it became his final act."

As the 2002 suicides of 89-year-old Admiral Chester Nimitz jun and his 86-year-old wife Joan proved, many want to choose the place and time of their final act, and to afford themselves some dignity in their departure rather than wait for the degradations of time and age.

The euthanasia movement is allowing people control over what was once considered beyond our governance. Part of that can be attributed to the baby-boomer generation and its insistence of its "rights," says McIntosh. After the rights of freedom of speech, expression and lifestyle, why not death in the manner of your choosing?

We are gaining more insight and techniques to deal with this ultimate rite of passage and making it a not unpleasant experience where possible.

But in the end none of it changes anything. As Richard John Neuhaus wrote in the philosophical magazine First Things: "Death is to be warded off by exercise, by healthy habits, by medical advances. What cannot be halted can be delayed, and what cannot forever be delayed can be denied. But all our progress and all our protest notwithstanding, the mortality rate holds steady at 100 per cent."

And so our days go by, lived against the ticking of the clock and waiting for the news no one could say is unexpected. Death is the best trip of all, hippies used to say, that's why they leave it until last. It's also one of the few growth industries perfectly designed to keep pace with the world's expanding population. One per customer.

Eventually there may be acceptance, a soundtrack chosen, arrangements made, family called in to talk about their feelings, the plot picked out ...

Eventually there may be acceptance, a soundtrack chosen, arrangements made, family called in to talk about their feelings, the plot picked out ...

But we go to that great unknown alone, clinging to whatever belief sustains us.

Sinclair's columns were admired because they offered comfort in a secular society in which religious explanations don't have the hold they once did.

The ways he sought meaning in life were through simplicity, nature and a local landscape.

The philosopher George Santayana observed, "A good way of testing the calibre of a philosophy is to ask what it thinks of death."

Presumably if it tells you what you want to hear, it's a good philosophy. Which explains the popularity of Kahlil Gibran's benign poetic view: "What is it to die but to stand naked in the wind and to melt into the sun? And what is it to cease breathing but to free the breath from its restless tides, that it may rise and expand and seek God unencumbered?"

Whew, he almost makes you want to go.

But for a more mundane image: John Lennon, the Beatle who wasn't given the opportunity to prepare for his passing, said just days before his murder he wasn't afraid of death, it was like getting out of one car and into another.

If he was right, some of us plan to walk a red carpet between them.

Rita - Jun 20, 2009

Our culture denies the inevitability of death. Death is hidden, not spoken about as we all gaily try to be as happy as possible hoping to outsmart death. The one certain thing in our lives of constant change is that we are going to day. We need more awareness on a day to day basis about death. It doesn't have to morbid...in fact by familiarising ourselves with death surely we are making it easier to face our own and others when the time comes.All our lives we face little deaths: changes, seperations etc. Focusing on death in fact gives more meaning and vibrancy to our lives.

Savepost a comment