Graham Reid | | 6 min read

The walls of the modest unit in suburban Auckland where Huang Juo-Hua and his four-year old daughter live are almost bare. In the lounge there is only a meagre calendar, and a large photograph of Huang’s wife Luo Zhi Xiang, its frame decorated with flowers.

There is a whisper of a smile on her lips, yet the eyes of the pale, attractive young woman possess an unusual sadness.

There is another photograph in the house. Huang has that in a drawer. It is of the same woman in a coffin.

She looks like a piece of battered porcelain: her hair is gone, the eyes sunken and the cheeks hollow, the face is frozen and looks mummified.

It is hard to reconcile the two images.

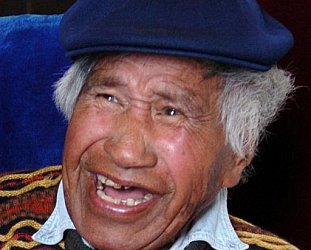

Huang -- in jeans and a polo shirt with an All Blacks logo -- wants to tell the painful story of his wife’s death. Her crime -- and his, which has caused him to flee China -- was to be a member of Falun Gong, the quasi-spiritual group that the Chinese government has been ruthlessly repressing for the past seven years.

Huang knows that by using his real name he may be courting unwanted attention from Chinese authorities, even this far from his homeland. But through a translator he says he now has little left to lose by speaking out. His wife is dead and his parents in China -- also practicing Falun Gong members -- are harassed regularly anyway.

Tragically, his is not an unfamiliar story.

Sometimes referred to Falun Dafa, Falun Gong is a way of living which blends aspects of Buddhism, Taoism, meditation techniques and traditional physical exercises with the teachings of the movement’s leader Li Hongzhi.

Li introduced his teachings in 1992 and insisted they be offered free to those who wished to learn. Because of its traditional aspects Falun Gong had wide appeal for many Chinese. Estimates on membership within China today range from many tens of millions to an unlikely 100 million. A figure of 70 million is commonly agreed upon.

Whatever the true number -- the current political climate makes it impossible to ascertain -- the movement grew rapidly with practitioners testifying to its positive effects for their health and general well-being.

Despite having some spiritual content, Falun Gong does not consider itself a religion and has no places of worship or a clergy. In a country where only five belief systems are lawful -- Buddhism, Taoism, Islam Catholicism and Protestantism -- Falun Gong was always going to be problematic for the government.

Ironically, given the persecution of members today, Falun Gong was originally encouraged by the government which viewed it as a wholesome and moral movement, and approved of its tenets: tolerance, compassion and truthfulness.

Founder Li lectured widely -- he is on record as condemning homosexual behaviour and permissiveness -- but in 1999 the ground shifted suddenly.

In early April of that year a strategically placed and provocative newspaper article criticised the movement, Falun Gong members rallied to protest, many were arrested and beaten, and on April 25 around 10,000 practitioners gathered outside the government’s headquarters in Beijing.

The size of the movement -- around 100,000 members in Beijing -- alarmed authorities which viewed it as a further visible manifestation of the Chinese Communist Party losing its grip on the people as it tinkers with democratisation and capitalism.

On June 10 the CCP established an extra-constitutional body -- the now notorious 610 office which has branches in all cities, villages, government agencies and schools -- to facilitate a crackdown.

In July the CCP -- concerned significant numbers of government officials, military and police personnel were Falun Gong practitioners -- declared the practice of Falun Gong illegal and police began arresting and detaining practitioners.

A Washington Post report noted that, “sources said that the standing committee of the Politburo did not unanimously endorse the crackdown and that President Jiang Zemin alone decided that Falun Gong must be eliminated”.

Since then the government has been hiking up the rhetoric: Falun Gong was first labelled unlawful, then characterised as an evil cult, and more recently as counter-revolutionary.

Lawyers in China have been ordered not to represent Falun Gong members.

Currently Beijing human rights lawyer Gao Zhisheng -- recognised by China’s ministry of justice in 2001 as one of the country’s “ten best lawyers” -- has been under pressure since winning a 2004 case for a Falun Dong practitioner who was illegally persecuted. In January he barely survived what has been described as a staged traffic accident set up by plainclothes policemen.

Repression of Falun Gong in China has been widespread and well documented, often with graphic photographs of tortured victims.

It is against this backdrop that Huang tells his story with deliberation and directness, and an unwavering gaze.

He met his future wife in Guangzhou, southern China in April 99. Both practiced Falun Gong.

In October, when the government defined “heretical cults” and declared Falun Gong to be one, he and Luo went to Tiananmen Square in Beijing to join protests and were arrested. He was taken to a prison his home province, made to do heavy labour, and deprived of food.

Luo was imprisoned for 15 days in Guangzhou and force-fed salt water when she went on a hunger strike.

After 20 days Huang was released and re-joined Luo in Guangzhou. They married in April 2000.

In November 2002 police came to their house and found Falun Gong books. They were arrested and detained in separate police stations. He went on a hunger strike and was force-fed with tubes up his nostrils which, on a first attempt, pierced internal organs.

When police learned his wife was three months pregnant she was removed from custody, initially taken to anti-Falun Gong brainwashing classes in the Huang Pu district, then to a hospital where she was guarded by officers from the 610 unit.

His wife’s sister learned where she was being held and visited.

On December 1 the sister saw a policeman run into the room where Luo was detained. The sister assumed Luo had escaped but on the street, three-storeys below, was the body of Luo.

As Huang tells it, his wife’s body had no broken bones -- which gives the lie to the 610 assertion that she jumped, as does her insistence the day before that she wanted to live for her baby‘s sake.

She had a severe head injury as if from a blow, and a second appeared after she was transferred to another hospital.

She died on December 4 aged 29 -- and Huang, still in custody, wasn’t informed until four months later. He saw her body briefly and could only identify his wife by a distinctive front tooth.

Released from detention in December 2003 where he had been forced to renounce Falun Gong and watch re-education films, he returned to Guangzhou. The following year he obtained a passport in his home province and fled to Bangkok in August 2004. Later that year a friend brought his daughter to him.

He applied for UN refugee status, was granted it and arrived in New Zealand -- a country he knows little about -- with his daughter in January.

His daughter is suffering very much, he says. She cries for her mother. It is she who puts the flowers around the sad looking young woman in the photograph.

Falun Gong has become more than an irritant to the Chinese government as it engages in sophisticated anti-government activities.

During early 2002 several successful hijackings of public television broadcasting time were carried out by Falun Gong members in China who tapped into cable television networks in several north eastern cities. Such overt anti-government actions are rare, and courageous, in China.

As longtime Sinologist professor Barend ter Haar of Leiden University in the Netherlands notes, “The continued perseverance of Falun Gong adherents/practitioners even inside the People's Republic of China in publicly expressing their resistance to the prohibition and persecution of their movement is remarkable, and easily misunderstood as fanaticism”.

A report by the US State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor published last month is damning in its investigation of human rights abuses by the Chinese government: physical abuse resulting in deaths in custody; torture and coerced confessions from prisoners; harassment, detention and imprisonment of those perceived as a threat to the Party or government authority; forced labour . . .

Estimates of Falun Gong adherents who have died in custody due to torture, abuse or neglect ranged from several hundred to a few thousand.

Most of the information about repression and torture of Falun Gong comes -- by necessity -- from Falun Gong itself or anti-government sympathisers. The Epoch Times for example, founded in China in 2000 and with editions worldwide, focuses on human rights abuses in China and gives significant coverage to Falun Gong. Its reports of human rights abuse are increasingly being verified by independent researchers.

In March 2006 Falun Gong documented the existence of a secret detention camp in Shenyang City -- where organs may be being harvested from live inmates -- which is part of the Liaoning Provincial Thrombosis Hospital and where 6000 adherents have been admitted, and none released. The authors of the report referred to it as a “concentration camp” and made the analogy with Auschwitz.

It is an increasingly common comparison being made by Falun Gong and human rights monitors.

The preface to the Falun Gong volume on investigations into the persecution of members in China opens with a quote by Nobel Peace Prize winner and humanitarian Elie Wiesel: “Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant. Whenever men or women are persecuted because of their race, religion or political view, that place must -- at that moment -- become the centre of the universe”.

Harassment of Falun Gong members outside of China is widely reported. Members here say they have been followed and photographed by people they believe to be CCP spies.

Many Chinese practitioners living abroad fear identification will attract the attention of the CCP’s international network of spies and lead to reprisals for family at home, or arrest on their return.

Yet in a small unit in Auckland, as his daughter arranges fruit in front of the photograph of his late wife, Huang Juo-Hua speaks through the translator.

“He doesn’t worry about himself now,“ she says, “and wants to use his real name to tell the truth about Falun Gong persecution in China.

“He wants people to know and believe him.”

Author's note: writing about Falun Gong does not mean I endorse the movement.

This article first appeared in the New Zealand Listener in April 2006

post a comment