Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Should Venice sink beneath the sea, it is possible the city could be reconstructed exactly by referring to the millions of photographs tourists have taken of every palazzo, piazza, corner and calle.

On any given day -- in bitter winter or the smelly humidity of summer -- Venice is crammed with visitors snapping and filming.

Venice’s decaying elegance, arguably an art statement itself, offers so much visual information that photographs become essential prompts to memory.

This is especially true during the Biennale which, in its breath and scope, is an art-fest like no other -- and most of the artists, pavilions and exhibitions thankfully permit photography.

Much of the Biennale, which runs until late November, takes place in the Giardini or nearby Arsenale -- the former a cool garden area of established national pavilions, the latter converted warehouse space on a former military site -- but exhibitions are all around the city and nearby islands.

Venice also boasts dozens of established galleries (many selling kitsch paintings of the Grand Canal with gondolas but some offering cutting edge contemporary work) as well as the Accademia (from Bellini and Canaletto to Tiepolo and Veronese) and the Peggy Guggenheim Museum with its seminal collection of early 20th century artists (Picasso, Ernst, Dali, Magritte, Braque etc.)

With dozens of special exhibitions coinciding with the Biennale (the Guggenheim has late-period assemblages by Robert Rauschenberg), Venice at this time can be an art marathon. The smart art tourist avoids the Biennale’s opening weeks and lets the celebrities get well clear, and by six weeks in -- when I was there -- a more sedate appreciation can be adopted.

The Spanish have pole position in the Giardini -- theirs is the first pavilion you encounter inside the main entrance -- and this year the massive mixed media paintings by Miquel Barcelo conjure up aerial sea and landscapes which refer to cartography as much as Impressionism.

Exceptional work, and just some among dozens in the Giardini.

For me however the most impressive work is at the Arsenale where young Italians present powerful statements: Aron Demetz’s roughly hewn cedar sculptures of standing figures eerily dripping with clogging resin; Giacomo Costa’s light boxes entitled Private Garden where the creeping encroachment of Nature has overtaken the ruins of a crumbling, anonymous city; Matteo Basile’s disconcerting Cibachrome photos of figures in strange landscapes . . .

This is genuinely provocative, interesting and commanding work. And there is much more.

Yet this Biennale -- my third -- also offers a considerable amount of indifferent work, small ideas essayed into relevance by their curators who imprint meaning on the mundane, and threadbare ideas re-presented with that coded and clichéd language which speaks of mapping territories, questioning relationships and so on.

In this broad context, and on their own merits with adopting the default position of the cheerleading patriot, the exhibitions by the New Zealand artists Judy Millar and Francis Upritchard are to be counted among the best of the Biennale.

Although not in the high-profile Giardini or Arsenale, Millar and Upritchard enjoy even better venues than did et.al whose undeniably powerful 2005 installation The Fundamental Practice was a short walk from the Giardini.

Both Millar’s Giraffe-Bottle-Gun and Upritchard’s Save Yourself are along the most popular route between the railway station and Saint Mark’s Square via the Rialto Bridge. Better spaces could hardly be imagined and Millar in particular -- her work in a highly visible church -- takes full advantage of it: above the entrance hangs a large banner.

Upritchard’s space, a palazzo on the Grand Canal, seemed rather less well utilised. Both Iceland and Singapore nearby had attention-grabbing sandwich boards outside (I was told Upritchard would be getting one, but this was six weeks in after all) and because her exhibition space is in a building with private offices you have to ring a bell to be buzzed in through the front gate.

The signage was poor and the banner on the Grand Canal had been removed (something to do with its size) -- although I was assured it was being replaced.

But in a context where artists unashamedly promote, these seemed like opportunities lost.

Information about New Zealand art (an interesting and explanatory DVD of both exhibitions, a few display books) is also tucked in a back room at the Millar.

And the works are worth drawing attention to.

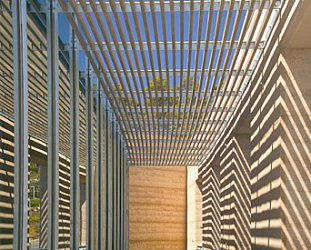

Millar’s installation of large, printed abstract canvasses (left) are of powerful immensity which respond to the given environment. The seemingly whirling cylinder at its centre -- all suggested speed in this otherwise quiet space -- mirrors the circularity of the church’s dome, its surfaces referring to marbling as much as motion.

The large standing panels (ironically designed for another space but perfectly in context here) suggest construction/deconstruction and invite you to piece them together, to consider their spatial weight, and to locate their colours in the church’s paintings.

An exceptional work by any measure.

As is Upritchard’s: small, delicate and disturbingly quiet figures in dance poses or meditating, mysteriously grouped characters rendered in fine detail which raise questions but offer few answers.

This is work which makes you stop, consider and return to. You couldn’t say that about a lot of the other artists’ work.

The breadth of a Biennale is almost impossible to assimilate or distil, but this time there is much which can be passed over lightly. Some works are “experimental” and only prove not all experiments are successful.

Many have familiar ideas reiterated to lesser effect; artists tools are offered up as “iconic” (they aren’t) and photographs of mundane objects are “all associated with a personal search for belonging”.

Unexpectedly, the United Arab Emirates weighs in with a witty and subtle concept which skewers the pretensions of such art practice and curatorial hyperbole, although it’s parody is so refined many take it at face value and walk past it. It is apposite in a Biennale where many artists seem to take themselves far too seriously and their work not seriously enough.

“Sometimes I thought the joke was on me,” said Dale, a professor of drawing from Kentucky whom I met one afternoon.

We were on the Rialto Bridge and just metres away a pretty young girl in a Carnival mask was having her picture taken by an elderly photographer.

Behind him people were taking photographs of her, and of her and him. Or of each other, the bridge or the gondolas below.

You sensed that, the Biennale aside, this was Venice going about its business: being a beautiful backdrop. And being photographed.

post a comment