Graham Reid | | 6 min read

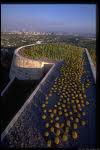

High in the hills overlooking Los Angeles, The Getty Centre offers

a commanding view.

“Yeah, on a clear day you can see smog forever,” says a droll

Angelino as he stares into the blue-grey gauze which lies lightly

over his city on this typically perfect, dry day.

That said the Getty, as it is commonly known and which opened 18

months ago, is beautifully appointed on a 46ha site above the San

Diego Freeway in Brentwood. It looks from the Pacific Ocean and

across the greater Los Angeles area in one direction, and to the

Santa Monica Mountains in another.

Little wonder Angelinos sometimes come here to simply wander

through the gardens -- designed by Robert Irwin -- and have lunch in

the sun with the busy world far beneath their sight-lines. Up here

it’s sky above and world below -- and art all around.

Built for about $NZ1.75 billion, the Getty art museum has seen

more that two million visitors since its opening in December 1997.

And oddly in this city of the automobile, the carpark allows for only

700 vehicles so it pays to book ahead. The many visitors who arrive

by bus or taxi -- or on skateboards or in-line skates, because this

is Los Angeles after all -- don’t need reservations.

The Getty certainly rewards any effort made to get to it.

Designed by Richard Meier, the centre effects the marriage of

handsome design and functionalism. Meier’s vision and the Southern

Californian climate has allowed for that rarity in art museums, an

effortless union of interior and exterior space.

Paintings on the top floors are exhibited under natural light.

The Getty is considered one of the great museums and locations --

but Meier’s bull-headed vision to realise his dream, and the

museum’s future direction, have been the stuff of protracted

controversy.

Of current concern is the Getty’s acquisitions policy most

recently under fire from Los Angeles Times’ art critic Christopher

Knight, who berated the museum for letting Georges Seurat’s 1884

Landscape, Island of Grande Jatte slip through its fingers.

Knight rightly noted that Seurat is internationally regarded as

one of the finest by the French pointillist Impressionist. This

painting was the perfect and necessary counterpoint to the Getty’s

Entry of Christ into Brussels in 1889 by James Ensor, a powerful

Expressionist work the museum snapped up a little over l0 years ago.

The Seurat, however, is now in Steve Wynn’s collection in his

Las Vegas casino, Bellagio. He picked it up for a tidy $NZ70 million.

The Getty says it considered bidding for it, but determined it

wasn’t a good enough example of the artist’s work -- a

breathtaking assertion. Knight suggests the museum’s running costs

(“a voracious money pit") meant it simply didn’t have the

readies for such a major purchase.

In a front-page Times article Knight noted that while the museum

was bolstered by a trust with an annual endowment of $NZ10 billion,

there were enormous outgoings.

The Getty has six principal buildings which collectively house the

J. Paul Getty Museum, offices, an auditorium, conservation institute,

the Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the

Humanities, an education institute for the arts, the Getty

Information Institute, the Getty Grant Programme, and a restaurant

and cafe.

lt is impressively large, as befits what has been described as the

most expensive and extravagant museum in the United States.

With facades of rough travertine stone chosen to evoke

traditionalism and endurance (though a substitute for the architect's

original concept of white enameled aluminium after complaints from

the neighbours), the place has a cool, assured ambience and sits

comfortably within the topography of the sometimes arid Californian

hills.

The Getty is expansive enough to accommodate large exhibitions.

Running at present are extensive exhibitions by the photographer

Brassai, the intelligent and informative pairing of the Italian

renaissance painters Ercole de Roberti and Dosso Dossi (complete with

x-ray analysis of one of Dossi’s larger works), an impressive

display of medieval illustrated manuscripts with educative displays

on book illustration and construction, sculpture exhibits, and more.

Already this year there have been acclaimed exhibitions of Dance and

Photography, the seldom seen photography of Edgar Degas, some small

Van Goghs, and changing displays from the museum's extensive archives

and collections. And most of these exhibits come with explanatory

notes and tie-in education programmes.

But the Getty did not arrive at this point without its

shortcomings or critics.

Meier, a visionary Modernist architect, drove his particular

vision of the museum for 14 years and clashed repeatedly with almost

everyone eise involved, notably Irwin and museum director John Walsh.

A behind-the-scenes documentary about this titanic struggle of

ideas, ideologies and egos, Concert of Wills: Making the Getty

Centre, captures the drama.

But despite Meier’s genius being largely realised -- and the

finished complex greeted with critical and public acclaim --

attention has turned to what is in the galleries. And, as Knight

pointed out, what is not.

Some say the feast of art can quickly turn into a smorgasbord, and

the slightly chaotic permanent exhibition largely reflects the

idiosyncratic taste of its benefactor, the late oil tycoon J. Paul

Getty.

The gardens -- a source of a lengthy dispute between Meier and

Irwin -- may be impressive in Los Angeles, a city not known for its

proud domestic gardens, but to outsiders it can look little more than

a well-designed, constrained collection. Plants which line the

zig-zag path that crosses over a trickling stream and leads to a

concentric display are regularly changed. But when lined up against

the great museum gardens of the world, it can look meagre.

And despite its size, the Getty is already cramped and the trust

has had to lease additional, expensive space in nearby Santa Monica.

It is also having to look at adding more parking spaces, there are

continuing renovations to Getty’s original villa in Malibu which is

scheduled to open in 2001, the numerous research and conservation

programmes are draining money and it demands a large staff.

The year before the Getty Centre opened the museum’s

acquisitions budget was slashed from $NZ92 million to $NZ50 million

and the figure is even lower today.

As a result, since its opening the museum's acquisitions have been

unimpressive. Knight listed only two major paintings, four

sculptures, three plaques, a Byzantine manuscript, 123 photographs

and other smaller works.

Certainly there have been generous gifts and endowments, but the

Getty itself appears to letting acquisition opportunities go by while

it struggles with its day-to-day running costs and problems.

So impressive though the Getty Centre may be -- and it is

certainly that -- there is also disquiet as to its future direction.

Whether what's inside continues to match its impressive exterior is

the question.

post a comment