Graham Reid | | 8 min read

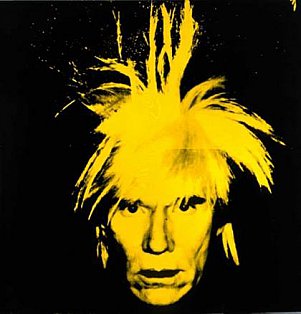

“People are always calling me a

mirror and if a mirror looks into a mirror, what is there to see?” -- Andy Warhol.

There's a scene in an Austin

Powers movie in which the superspy and international man of mystery

is in his London bachelor pad. Amid the iconography of the Swinging

Sixties is a large multiple portrait of Powers rendered in flat,

garish colours. In its signature style it could only be by one

artist.

Even now -- twentysomething years after his death and

more than 45 since establishing his distinctive portraiture style

with screen prints of Marilyn Monroe - the work of Andy Warhol is so

immediately recognisable it can be parodied and paid homage to,

recreated in the artist’s absence - and allow us a smug snicker of

recognition.

If Warhol had known Powers back in '69

he undoubtedly would have done his portrait - and it makes no

difference that Powers is fictional. In some senses Warhol doesn’t

seem to have existed either. He just was.

But what was he? Genius or charlatan,

artist or advertising man?

Andy Warhol - the youngest of three

sons born to a Czechoslovakian immigrant family in unglamorous

Pittsburg in 1928 - was the Chauncey Gardner of the art world, the

empty mirror, the blank slate.

His most recognisable expression might

have been a yawn, if he hadn’t been so wearily detached as to be

bothered opening his mouth.

Gore Vidal said he was a genius with

the IQ of a moron. But, the argument goes -- and it could only be

developed by some one who hadn’t read a Naomi Campbell or Jackie

Collins novels – no one that rich can be that stupid.

Debate over whether Warhol more

properly belongs to the history of art or the history of marketing were rehearsed again with the touring exhibition The

Warhol Look: Glamour Style Fashion in the late Nineties.

Significantly the extensive exhibition, curated by the Warhol Museum, came with a slew of tie-in

merchandising and was mounted in Very Serious Art Galleries.

Warhol, whether you like him or not,

has been enshrined and canonised by the establishment. He’s in the

history books and proper galleries, has his own museum in Pittsburg

and people looking after his licensed product in Germany.

Art or commerce? It hardly mattered

then, it certainly doesn’t now.

But this exhibition was about fashion

rather than art, so there’s not the comfort of the familiar Famous

Soup Can here. Rather, it was a deep immersion into the shallows of

Andy-world.

Yet if Warhol himself will always

remain an increasingly elusive and neutral figure, taken together

this show offers a self-portrait refracted through diverse works

across several fields.

Helpfully – given Warhol’s later

free-range forays into film, music, performance art and publishing --

The Warhol Look is inclusive and loosely chronological.

From the Forties, when Warhol was a

fragile art student (he’d had three nervous breakdowns before his

teens), we see something of his obsessive collecting of movie star

and glamour photos from magazines.

The title of this section, At Home with

the Stars, is a clever crock: the stars weren’t at home, but insecure

and unattractive Andrew Warhola was, melding his anxious dream life

into theirs -- and collecting what would become his raw material.

“Today everything is badly made,"

his mother said in 1973, “and those beautiful things he loves, like

the old movies, were better made.”

The Fashion Tips with Andy section

collects some of his commercial illustrations and window designs from

the Fifties. There are recreations of shop window displays for swanky

New York stores such as Tiffanys and Bonwit Teller – and here is a

hint of an alter-Andy: there’s a youthful playfulness to his

commercial illustrations redolent of Jean Cocteau, Ben Shahn and

Erte.

For those who would dismiss him on the

basis of his later work, here is proof too that he could draw –

although some (Joan Crawford, 1962) look like the kinds of clumsy

portraits preteen fans used to send to the Beatles around 1964.

His fascination with shoes as fetish

objects is well represented in illustrations and painted lasts. Here

too are effigies of Warhol, the perfect substitute for a man notable

for his emotional absence.

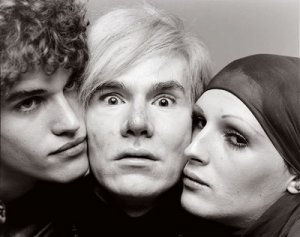

The Sixties are represented by Autopsy

at the Factory, Warhol’s famous silver-lined downtown warehouse

space which became a mecca for freaks -- and then the fashionable.

“A lot of people thought it was me

everyone at the Factory was hanging round,” he said, “but that’s

absolutely backward. It was me who was hanging around with everyone

else. People weren’t particularly interested in seeing me, they

were interested in seeing each other They came to see who came.”

And through those doors came Bob Dylan,

poet Allen Ginsberg, homeless drifters and other detritus of the

Great Society. And the Velvet Underground (no footage in this

exhibition; presumably Lou Reed’s lawyers were as protective of

their client as Warhol's), Valerie Solanis who would shoot Warhol in

1968, “superstars” off the streets, drag artists and wannabe film

stars who became the subjects of his passive, often non-narrative

films which even the catalogue concedes are more fun to talk about

than sit through.

“I like the boring things,” he said

at the time, as if that would excuse any old drivel. For his acolytes

it did.

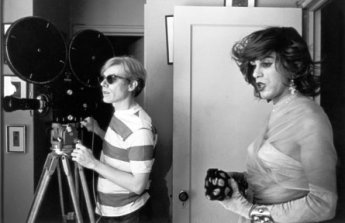

The exhibition includes his films Poor

Little Rich Girl, Chelsea Girls and Bike Boy, and screen tests for

the beautiful but doomed Edie Sedgwick, poet John Giorno, and a dozen

other Factory regulars whose talents (aside from Dennis Hopper) would

never translate much beyond 231 East 47nd Street.

Thereafter chronology and

categorisation is disassembled through Drag and Fashion and

Uptown/Downtown because after the Sixties -- being shot seems as

pivotal to Warhol’s career as Dylan’s motorcycle accident or

Lennon meeting Ono -- Warhol traversed the art and commercial worlds

as a dung beetle does a desert.

His autographic style became codified

and frozen, more cool and deadpan, and the elimination of

decision-making about rendering of surfaces eliminated both his

personality and that of his subjects from his Polaroid portraits.

Interview magazine -- of which the

exhibition has a number of displays of covers, photospreads and

fashion shoots -- became his in-house vehicle to flatter and pamper

the Uptown set.

His works in the Seventies and

Eighties, as he moved away from freaks to the fashionable, proved

only the power of a cheque-book and, like a moth attracted to the

brightest of lights, his tiny wings beat against the famous and the

feckless.

He might not have been a genius but he

had a gift, and in that captured the Zeitgeist of consumerism in the

Eighties. He did ads for rum, appeared on The Love Boat and fashion

catwalks, and died eight months before the stockmarket crash which

sent the crowd from Studio 54 -- his substitute Factory – into

rehab or real jobs.

Black Tuesday might have been the end

of what critic Robert Hughes called Warhol’s “supply-side

aesthetics” but, as with his beloved Marilyn, death can be a good

career move.

The Pope of Pop was gone; long live the

mandarins of marketing.

So, how to define the Warhol style?

His work across an indiscriminate

spectrum is enticingly insipid, transparent, endlessly repeatable,

neutral and neuter. It is the atrophying of expression and gestures

of effort, a Rorschach abstract in which we locate our own meaning.

In the Eighties Warhol may have

reinvented the genre of portraiture, but in it he became as

fraudulent as Dali, a court painter to the profligate rich for whom

his signature was like a passport into the Kingdom of the Chic.

His vacuous portraits -- blanded out

into outlines and flat colour -- hardly bear sharing a genre with

Goya’s portrait of Queen Maria Luisa, or Sir Joshua Reynolds.

The coalminer’s son from Pittsburg

was now delivering to women who lunch, their Uptown husbands a

vindication of their lives, an elevation to the level of Marilyn and

Liz, Elvis and Joan Crawford by Andy-association. Under the eye of

the Warhol Polaroid anyone could become a secular saint.

All you needed bo do was pay for the

privilege.

As with his films and interviews in his

magazine, his later work carries no special weight or virtue beyond

his name being attached to it, like a Calvin Klein tag on a shirt

collar Warhol liked that about it.

“If you want to know all about Andy

Warhol,” he said, “just look at the surface of my paintings and

films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.”

That very affectlessness of his art

lies at the heart of Warhol’s career and still attracts hostility

But Warhol was about reversals: he inverted the order which said

celebrity followed work well done, and where art was about the

one-off unique object he made multiples.

He found his superstars on the streets

and the artist was as important as his subjects.

The Warhol Look is a blockbuster by an

icon whose name is as synonymous with merchandising as art - and its

subject, being at that profitable interface, lends itself to

heavyweight promotion.

And all because of an opaque little man

who became his own greatest creation.

The enduring, perfect Warhol statement

is in the exhibition: one of his wigs, framed. No face beneath it.

The invisible man, only able to be seen through his work.

And even then . . .

post a comment