Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Jan Berry: The Universal Coward

On Christmas Day 1969, at age 18, I flew in to Saigon. It was 10 months after the Tet Offensive which saw Vietcong soldiers at the door of the American embassy in Saigon and the war was at a peak. I went to Vietnam because I was curious . . . and because could.

In fact, surprisingly, anyone could.

Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, was on PanAm’s regular route -- PA001 if I recall. But there was an obvious reason why most people wouldn’t want to go.

My vivid recollection was of the landscape beneath me as we flew in -- farmers’ paddocks pockmarked by hundreds of shell holes. There was supposed to be a Christmas truce but our pilot said the Vietcong had attacked the end of the runway -- there was certainly black smoke and soldiers running -- so even then I knew this would be an un-winnable war for the Americans: the countrywide jungle alone was dense and alien territory.

It would be 1995 before I got back to Saigon, now renamed Ho Chi Minh City, and -- 20 years after its fall, or liberation if you will, it had reverted to type, a city of opportunism and entrepreneurs as opposed to the more stately, crafty and controlling Hanoi in the north.

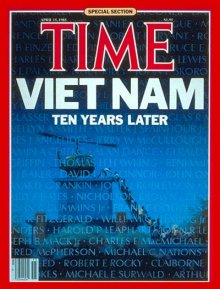

The American war in Vietnam was the defining international conflict for my generation.

It divided families and nations and even today remains etched in memories for the tragedies played out on the nightly news. Never again would cameras have such free access to battlefields. The horrors of war are too real for governments to show their citizens.

During the Vietnam period there were remarkable few films set in-country, only John Wayne’s inane and patriotic The Green Berets of ’68, a cowboys Vs Indians action-flick transplanted into South East Asia, comes to mind.

It’s curious however that today’s conflicts involving America -- you know where they are -- have spawned so many films and television series: the unheroic Over There and Generation Kill mini-series have been on New Zealand television, in cinemas there have been In the Valley of Elah, Green Zone, The Hurt Locker, Redacted, Home of the Brave . . .

Yet the current wars have not produced much in the way of songs -- outside of country music -- unlike the Vietnam war which was discussed on the airwaves in songs from all sides of the political and social spectrum.

From protest music by Phil Ochs, Bob Dylan, Tom Paxton, Marvin Gaye and Creedence Clearwater Revival to patriotic ballads by Staff Sgt Barry Sadler, Marty Robbins, Connie Francis and Craig Arthur (singing Son of a Green Beret, there were a lot of sequel and answer songs in the period), the jungle war was everywhere in song lyrics.

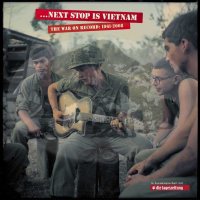

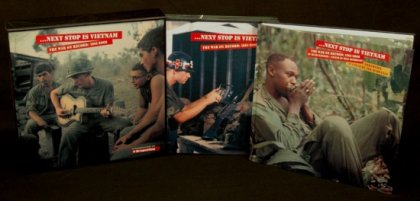

The extent to which the Vietnam was a topic of popular -- and sometimes very unpopular songs --- is brought home with an exhaustive, magnificently presented 13-CD collection Next Stop is Vietnam; The War on Record 1961-2008 which comes with a hardback book of the political background, extensive notes on each song and artist, and relevant photographs. There is also an extra disc of computer-compatible song lyrics.

Next Stop is Vietnam (its title from the Country Joe McDonald’s famous song Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag) comes from Germany’s Bear Family label and is a definitive statement on not just the (Western) music but the social and political backdrop from the bloody war to the generational hurts for returned soldiers.

Punctuated by radio spots from various presidents (Eisenhower, Johnson and Nixon), and the voices of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, vice president Spiro Agnew, anti-war activist Jane Fonda and moratorium speakers, this collection is an audio-doco of the war as it happened for people of all persuasions, whether they were soldiers in the field (there are many songs recorded in-country) or those on the anti-war barricades.

Or those who simply went into a local recording studio and put down their sentimental lyrics.

There are some truly dreadful "songs" such as Little Becky's Christmas Wish, often considered one of the worst "songs" of all time, in which five year old Becky Lamb speaks an open letter to Santa about her brother Tommy who was killed in Vietnam and wanting him home for Christmas. It is awful -- and there is just as bad sentimentality in other places in this inclusive coollection.

Almost every major artist -- the Kingston Trio through patriotic country artists like Merle Haggard and Ernest Tubb (the appalling It’s For God And Country and You Mom here) to Donovan, the Doors, the Plastic Ono Band (Give Peace a Chance) -- is included, although Neil Young’s Ohio is absent in the section about the killing of students at Kent State by the Ohio National Guard, and John Fogerty’s classic songs with Creedence (Run Through the Jungle and Fortunate Son) are here by Paul Revere and the Raiders.

But the rest are on parade. From blues artists (JB Lenoir, John Lee Hooker, Lightnin’ Hopkins) and dreadful kids’ songs wanting daddy home, to artists divided in song about the My Lai massacre and rather uncomfortable “letters” to soldiers (the scary Letter to a Buddie by Joe Medwick -- here -- which suggest his missus is having a great time in his absence with a friend who has moved in).

From

singers accusing dissenters of cowardice (Jan Berry, stay-home

patriot of surf-poppers Jan and Dean, with his despicable The

Universal Coward, an answer to Buffy Sainte-Marie's Universal Soldier)

to uncomfortable “letters” to/from soldiers, and blind patriotism which elevate heroism but would deny death is part of the soldier’s contract.

And there are those songs of the post-Vietnam period which look at the toll it had on returned American solders (Steve Earle's Copperhead Road), the emotional resonance of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Springsteen's Galveston Bay from his Ghost of Tom Joad album, Billy Ray Cyrus (Some Gave All) . . .

They are all here in songs which are moving, frightening, laughable and few where humour fails because the “artists” comfortably at home pretended it wasn’t so bad over there.

The hawkish alongside the mawkish.

And many, very many, songs which will have a catch in your throat.

Next Stop is Vietnam is a collection of emotions as much as songs and soundbites, and a history lecture come to life . . . with a much more interesting soundtrack.

Not a world you might want to fly into -- so be very glad you can get out.

I was.

Next Stop is Vietnam is available from Bear Family in Germany here, or New Zealand readers can contact Yellow Eye Records in Dunedin here.

Vietnam today of course has its own music, as it always did. For that have a listen here. For another story from after the war and about its victims, a Vietnamese one in this case, go here.

post a comment