Graham Reid | | 7 min read

Michael Nyman: The Promise (from The Piano)

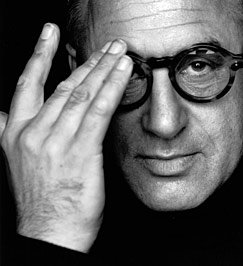

For director Jane Campion to have as

noted a composer as Michael Nyman to score the soundtrack for her

film The Piano was as simple as a phone call. From his home in

Toulouse, Nyman --

whose extensive career is best known

for his soundtracks to Peter Greenaway films – acknowledges that he

knew Campion’s previous films Sweetie and An Angel At My Table and

"one does sit around thinking of a number of people one would

like to work with. Jane was definitely one."

Then the phone call came. And after the

increasing frustrations working with Greenaway (which ended

acrimoniously after Nyman accused the film-maker of “unintelligent"

use of his music in Prospero’s Books, Campion proved “a dream to

work with.”

“Apart from her brilliance and

competence she’s a fine human being and we have an excellent

relationship on a social level. Even if we never work together again

she will be a good mate."

And Nyman, whose discography and

credits include numerous films and documentary scores, is unstinting

in his praise for Campion’s The Piano, calling it the only film of

which he has no criticisms.

"I’ve seen it five or six times

already and am constantly discovering things. Whether Jane intended

it to be that dense and rich I don‘t know, but I like to think it

was intuitive.

“When Greenaway talks about his films

he goes into great length on the meanings and nuances and resonances.

Jane’s subterfuges are more in the work itself and the pleasure

comes in finding them.”

For an audience a chief pleasure is

Nyman’s haunting music played by American actress Holly Hunter, for

whom the composer specifically wrote.

For an audience a chief pleasure is

Nyman’s haunting music played by American actress Holly Hunter, for

whom the composer specifically wrote.

The music in The Piano is a kind of

double-take for Nyman; first to cast his distinctive stylistic

signatures aside and write not as a late 20th century composer but as

an 19th century woman, and then not as one who plays the repertoire

of the day but her own music.

"I can talk about the process much

more impressively now that it is done,” he laughs, “but it was

rather difficult to achieve in terms of the character of the music."

First he had to write pieces for Hunter

“who turned out to be a very, very efficient player and quite at

home on the slow romantic pieces,” then reassess the pieces in

terms of their domesticity relating to the character Ada which Hunter

plays.

Because Hunter was so proficient he

rewrote some pieces (“she sailed through the first things so I made

them more difficult”) and deliberately drew upon Scottish folk

tunes to account for the background of Ada.

“And the most enjoyable part is that

I’ve had two cracks at it,” says Nyman whose career began in the

early Sixties but fell silent for 12 years until his two Decay Music

pieces in 1976.

“I wrote for Holly’s playing in the

film then played myself on the recording of the album with members of

the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra."

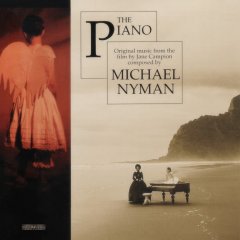

That soundtrack album has met with

astonishing success and has the hallmarks – and increasingly, the

sales figures -- to make it transcend the narrow constraints of

soundtrack music into the popular arena.

That gratifies Nyman -- not the least

for the message it delivers to Greenaway -- because his career has

been one of hurdling the artificial barriers that some would impose

on music of various kinds.

After graduating from the Royal Academy

of Music and Kings College in London in the early Sixties, Nyman’s

background in music is as diverse as English baroque styles and folk

tunes of Romania effectively sidelined him from contributing to the

contemporary classical world of the period. So be wrote about music

for various magazines and newspapers. His book Experimental Music, Cage

and Beyond of 1974 has become a seminal text on contemporary music.

He coined the word "minimalism"

(and consequently was often mistakenly identified as a practitioner

of the austere, repetitive style) and now looks back on that period

as “a bit Golden Age-y.”

It was a time when classical composers

such as John Tavener, now enjoying popular success with his The

Protecting Veil, was recording for the Beatles’ Apple label and

Nyman himself could write columns for The Spectator on artists as

diverse as the American avant-garde satirical group the Fugs or the

English classical composer Peter Maxwell Davies.

“If you think of musical culture as a

mansion it was possible in the Sixties to move from one room to

another and have a totally different musical experience in each one

. . . and then be able to relate them to someone in the next room.

“If you think of musical culture as a

mansion it was possible in the Sixties to move from one room to

another and have a totally different musical experience in each one

. . . and then be able to relate them to someone in the next room.

“These days Billboard [the weekly

bible of the music industry] has a section called Crossover, so

everything has been institutionalised. Composers like Stockhausen and

Boulez who were pretty cool in the Sixties and were talked about by

-- and maybe even talking to -- the Beatles have all reverted to type

and have been put into the avant-garde composer category again and

had the door to their room closed on them.”

Nyman expresses great gratification to

learn that his album of The Piano was recently reviewed in the pop

and rock column of the Sydney Morning Herald -- right next to the classical reviews. Ironic too, he points out, given The Piano is the

most classical thing he has written.

“It's 19th century piano

music with fewer Nymanesque liberties to convince the audience they

are listening to Ada playing from within herself.”

Yet such a self-imposed brief is well

within Nyman’s considerable capabilities which those who only know

of his Greenway soundtracks -- The Draughtsman's Contract; The Cook,

The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover and Prospero's Books among them –

may find surprising in its diversity.

As far back as the early Seventies he

was one of a generation of bright young things who appeared on the

appropriately named Obscure record label ran by former rock

keyboardist with Roxy Music, Brian Eno.

Today Nyman, as with many of his peers,

is in demand for commissioned works.

In the first quarter of last year he

undertook half a dozen pieces, some of which have found their way on

to his recent Time Will Pronounce album on the Argo label.

But as with his contemporaries, Nyman

is adept at handling the business end of music and talks freely about

searching for a new record label and of deliberately stretching

commissioned works in various directions to extend his own musical

vocabulary.

He has written opera (The Man Who

Mistook His Wife For a Hat), string quartets (his Second String

Quartet was originally written for a South Indian dancer but is now a

concert piece) and writes equally well for solo harpsichord (The

Convertibility of Lute Strings), brass instruments (For John Cage by

the London Brass) and saxophone (Where The Bee Dances). He even has

his own group, the Michael Nyman Band. His next commission is a

40-minute solo violin piece commissioned for a Japanese fashion

designer but which he expects will be released on album and therefore

enter the solo violin repertoire when the music is published.

And The Piano is by no means finished

yet either.

“I have rewritten it again as a

concerto which will be released by Argo and will have its premiere

this month in Lille. And now I am turning that concerto into a double

concerto which the Labeque sisters will be recording for the Sony

Classical division.”

Nyman is a self-confessed market

pragmatist who admits his own band “charges around the world

because people know our records are selling. We sell better than

anyone these days - except Gorecki -- so promoters and people who

commission can guarantee an audience. So we are all using each other.

“But it is terribly important that

music has an audience and that’s why I'm delighted by the success

of The Piano [album].

“I still think Time Will Pronounce is

the best thing I’ve done in five years and it is frustrating that

it doesn’t get the profile that, say, a film soundtrack does.

“But film is a wonderful and

artificial medium and with Greenaway I always thought of the film

part as simply an illustration of a concert.”

post a comment