Graham Reid | | 11 min read

Since I first seriously reviewed an album about 40 years ago (the George Harrison triple set All Things Must Pass) I guess I have written in excess of maybe 6000 reviews of records/CDs/tapes etc -- and of course I have heard many, many more than that. Some people are well-read, I am well . . .

Hmmm, there must be a word for it.

In that time I have also reviewed hundreds of books, maybe a few hundred or so movies and DVDs, written about quite a number of restaurants and bars, and even done a few theatre and comedy reviews.

In short, I have become pretty aware of the role of the critic.

Which is why I read with interest an Observer article reproduced in the Weekend Herald [2007] about the Royal Shakespeare Company banning critics from a production.

The production in question was their King Lear with Sir Ian McKellen in theatre's most challenging role.

What the article said was this: here was a much anticipated production by a great company and with a real crowd-pulling star in the ranks -- and yet there had been no reviews. The director Trevor Nunn had "imposed a complete ban on critics attending the play until May 31, when it will have only three weeks left to run," according to the article.

The RSC's argument was that one of the leading ladies had dropped out of the production because of a hurt knee and her role was being taken by an understudy. This is every director's nightmare -- the actress was to have played Goneril and was injured on the eve of press night -- and so you can have every sympathy.

But banning critics?

The rationale was the RSC would now only be able to give "a limited account of the production". Some critics complained -- but they also complied. No reviews appeared in the major dailies.

It is here you start to wonder, just what the role of the critic is: are critics responsible to the theatre company, film industry, publisher or artist? Whose interests are they there to serve?

The film-maker Mike Radford who received a critical drubbing for White Mischief and fled to Italy (where “people had no axes to grind, they liked and appreciated my work”) wrote an odd piece in London’s Time Out in November 95.

He said he didn’t mind bad reviews (although nothing in his article suggested that) and he concluded that, “most [film] critics have no real understanding of their job. Let me define it. It is not to influence the general public who don’t give a stuff anyway about what they say, but to influence the film-makers who do care. They help to define a film-maker’s perception of himself and the industry in which he works, and that is great and formidable responsibility.”

I couldn’t disagree more.

As a critic I have always thought my first and perhaps only responsibility is to the reading public, not to the musicians who make an album, the author, a theatre company or the artist.

Artists often wail that they don't mind criticism but it should be "constructive criticism" -- whatever they mean by that. But a critic isn't there to tell an artist what to do, that way madness lies. I used to have to point out to many young musicians that if they wanted critical comment about their musical direction or whatever that this was something to be done by themselves, or in consultation with their manager, record company and so forth.

The reviewer who gets the album in the post can only deal with the artifact in hand. You critique what you hear or see, not what you would have liked to have heard or seen.

There is also the widespread impression that the critic is there as some kind of malevolent gatekeeper determined to keep an artist’s particular genius from reaching the wider world. Frankly I have never met a critic or reviewer yet who engages in that kind of personal conspiracy.

I remember Murray Cammick who was then editing the rock magazine Rip It Up telling me of phone calls he would receive from musicians who felt that because they hadn’t achieved critical acclaim some time back that they were somehow now marginalised by his magazine.

Murray pointed out that neither he nor his writers had the time or energy to hold grudges or engage in vendettas, they had a magazine to get out.

I have always adopted that approach also: if the last book/CD/exhibition or whatever didn’t make me excited it does not naturally follow that the next one won’t either. As a critic you genuinely go into these things hoping for the best. Who would drag themselves across town at night for the pittance that is paid to write a review if they were going into a performance with the expectation that it will be bad?

I am also of the belief that if the public is paying at the door to see a performance, for example, then that performance is up for critical comment. I have never had time for the notion that we cannot expect a theatre company, say, to get it right on the first night. Okay, we will be a little forgiving -- but if someone from the public has paid at the door why should they not expect the very best?

Otherwise opening night would be half-price, right?

Because I also believe that the critic’s responsibility is to the audience not the artist I don't have much time for obscure writing because I think it masks honest opinion.

At a panel discussion at Elam art school once, the Herald's art writer Terry McNamara and I spoke about the need to communicate clearly with the reader. Another writer said she felt she had no responsibility to communicate with readers. Weird.

I looked at her stuff and found it wilfully polysyllabic, drowned in coded language and absurd art-speak. It was arrogant and exclusive writing designed -- I thought -- to promote the writer's career and profile rather than being there to illuminate or critique. It was also easy to parody.

I love a quote in Tom Wolfe’s amusingly heretical poke at modern architecture From Bauhaus to Our House. An architecture critic speaks of “the articulation of the perimeter of the perceived structure and its dialogue with the surrounding landscape”.

This idea of a "dialogue", Wolfe says, caused a Harvard logician to ask, “What did the landscape say?”

Far too often critical writing -- especially in the plastic arts, you couldn’t get away with it in rock’n’roll -- is elitist, coded, full of jargon and wilful abstractionism which needs to be hauled up short in exactly that Harvard manner.

That said, I cringed when I read this bunch of masturbatory nonsense about the Sex Pistols’ God Save the Queen single by the US writer Greil Marcus: “ ’Tobias Crisp held that ’Sin is finished. If you be freemen of Christ, you may esteem all the curses of law as no more concerning you than the laws of England concern Spain,’ “ Christopher Hill chronicled in the 1975 Penguin edition of The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution. . . .”

There was more from Marcus along those lines -- about God Save the Queen? -- but as Casca says in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar: “I can as well be hanged as tell the manner of it. It was mere foolery; I did not mark it.”

So, the role of the critic?

Let us get rid of a few shibboleths here. "But it is just one person's opinion." I agree. But it is one person's informed opinion, and that is the difference. Critics, by virtue of having heard/seen/eaten/viewed/experienced/etc more have wider frames of reference and bring that to bear, mostly intuitively, in what they write.

For many reasons, not the least that this country is a small town, I believe that critics in New Zealand are, if anything, often inclined to err on the generous side.

Lord knows I have been to many theatre productions which I would have dumped on mercilessly because they seemed ill-conceived, poorly written or badly paced, or woefully acted -- only to read a critic praising the work. (Yes, sometimes faintly, but praising it nonetheless.)

So critics can be wrong?

Of course. I have been "wrong" many times -- and by that I mean I have perhaps been unduly praiseworthy or unduly harsh. But when people have complained that I was too harsh I generally mention this: not once in my very long career as a critic has any musician called me to say I was wrong because I had been too generous towards them.

As W. Somerset Maugham noted in his 1938 reminisence The Summing Up: "I have never met an author who admitted that people did not buy his book because it was dull." And later: "In the production of his work, the author has fulfilled himself. But that is not to say it has any value to anyone else. The reader of the book, the observer of the picture, is not concerned with the artist's feelings. The artist has sought release, but the layman seeks for a communication, and he alone can judge whether the communication he offers is a by-product. I am not speaking now of those who practice an art to teach: they are propagandists and with them art is a side issue."

And in contemporary times we often encounter art which is therapy for its creator.

But I have always found it interesting that musicians have never complained when I have over-inflated the value of their work.

What also interests me is that if I hail an album by an artist I am invariably right and they or their management and/or friends respect my good judgement. If however I fail to find the same genius at work on a subsequent album I am consigned to the rubbish heap as a hopeless critic -- by the same people who respected me previously.

How could I have suddenly changed and gone from insightful to useless?

Musicians would sometimes send me albums asking me to comment on them, but only review them if I liked them. Huh?

I believe there is an old saying from Broadway days, “If you aren’t praising them, they aren’t listening”.

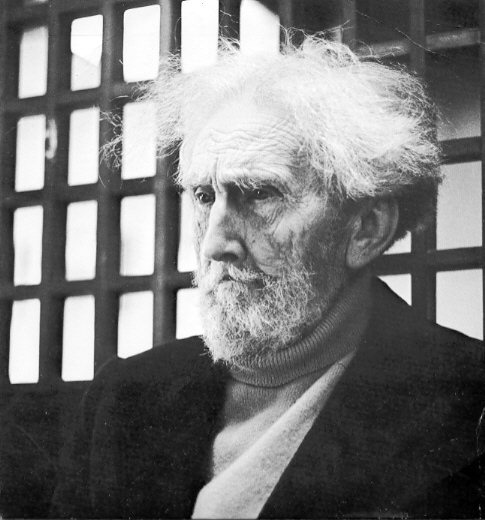

I have also always been of the opinion that artists place a disproportionate emphasis on the actual influence of critics: above my desk for many years I kept a quote by Ezra Pound from a letter he wrote to the American avant-garde pianist, composer and author George Antheil: "The yawps of the press are certainly of no importance. Nothing is to be expected of them, least of all any sort of comprehension of anything. Get your stuff printed and the three dozen people in the world capable of understanding it will eventually discover that it exists".

I believe that: work of value finds its audience. Sometimes not immediately however.

Somerset Maugham again: "If it is true that talent consists in a certain facility combined with a peculiar outlook on the world it is very understandable that originality should not at first be welcomed. In this perpetually changing world people are suspicious of novelty and it takes them some time before they can accustom themselves to it. A writer with an idiosyncrasy has to find little by little the people to whom it appeals."

I would disagree with him one one point here: I believe too often today people are seduced by novelty. The world of contemporary art and avant-garde rock music is littered with examples of superficiality -- often essayed into life by curators and cheerleading "critics" -- but which lack any resonance beyond the surface.

Some artists on the receiving end of criticism have occasionally said to me, “it’s all right for you, you aren’t the one being criticised”. To which I point out what I think is obvious: as a journalist writing for the biggest newspaper in the country across a wide range of topics my work was up for criticism every time it appeared.

Was I ever criticised? Was I ever!

But early on I adopted the very simple position: Never explain and never complain.

I stuck with that when my first book Postcards From Elsewhere came out: it would have been very easy for me to pen a tart letter to one reviewer who said that I had written about a particular country (which I have never visited), and another who said I had enjoyed a place when it was quite clear from what I wrote that I hadn’t.

But what would be the point: my work was out there and it would find its audience, so I let such trifles go.

These people weren’t being malicious (I don’t think), I just believed they had got it wrong -- and as a critic myself I have to allow them that right, stupid as it may have seemed to me.

Should I not send my next book to these critics? Blacklist them in fact?

Which bring us to the case of the RSC and the banning of critics: I have no idea how things work in Britain but I would have thought that if any theatre company in New Zealand tried to impose a critical silence because they thought their production needed a bit of an easy break, they would be told with absolute certainty what the critics thought about that.

It has been tried a few times but I reiterate my two-cents worth: the second some paying customer walks in the door to see a show it is fair game.

As one who always reads reviews, even when they are about arts which I have little interest in, I admire many New Zealand critics. They do a difficult and often thankless job in a small community where backbiting and personal attacks are endemic (Yes, I've had the drunken abuse in bars, it comes with the turf.)

Speaking to some journalism students recently I posed this question to give them an idea of the minefield through which a critic has to walk, let alone try to dance in words on a bare page.

Imagine you are lucky enough to get a job at the Herald and you get a call from a small theatre company putting on a show at Silo. They want some publicity and your editor says, "Yeah, go for it".

You go there and you meet the director and it turns out one of the cast is someone you knew from school. You do a nice interview during the course of which the director tells you how they took out a mortgage on their house to get the show on stage -- so they really need full houses for the season. They are appreciative of you taking the time to come and speak with them.

You leave on good terms, write your piece and they ring and thank you for it later.

The day before they open however your editor says, "Hey, we should review that show. You know all about, why don't you go along?"

And so you do.

And it is bloody awful.

What are you going to do?

Are you going to be true to yourself and your readers knowing that you might kneecap their season, and piss off people you actually liked?

If you waver over your answer to that question you might not have the mettle to be a critic.

It is thankless role and the best you can hope for is you hear some great music or see wonderful performances that others might not.

So it's not easy being a critic.

But someone has to do it -- unless of course the Royal Shakespeare Company says you shouldn't.

post a comment