Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Arvo Part: Tabula rasa (for two violins and prepared piano)

The story is such an improbable cliché

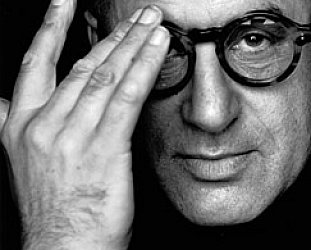

it can only be true: one night in the late 70s while driving between

Stuttgart and Zurich, the famous jazz producer Manfred Eicher heard

music on the radio so entrancing he had to pull over to listen more

closely.

Eicher – founder of the ECM label

which has a reputation for music of often profound austerity – was

so enthralled by what he was hearing he made efforts to track down

the composer, Estonian Arvo Part.

Eicher – who had been classically

trained – was so taken by Part's piece Tabula rasa that

within a few years he had launched the ECM New Series imprint of

contemporary classical music with an album of Part's works, Tabula

rasa being the title track.

In a story free of irony, there is one:

Part's Tabula rasa is less a demanding piece of contemporary

classical music than a work which owe a debt to various ancient

traditions.

On the occasion of Part's 75th

birthday in September 2010, ECM presented a special edition of the Tabula

rasa album which comes in 200-page hardback book with a brief

essay and the scores of Part's pieces on the album, including a

facsimile of his previously unpublished original scores for Tabula

rasa and Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten.

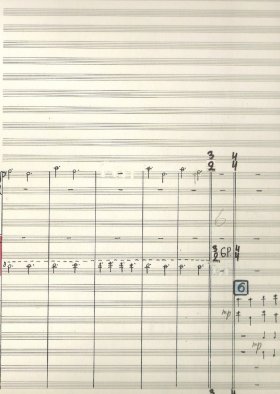

A glance at the original Tabula rasa

score for two violins, prepared piano and orchestra, confirms why

violinists Gidon Kremer and Tatjana Grindenko were confused when they

saw it in 1977.

“We were all a bit surprised by the

the empty pictures of the score,” Kremer told Gareth McConnell of

The New York Times. “It was all tonal and so transparent.

There were so few notes.”

It also explains why Part has been

lumped in with John Tavener and Henryk Gorecki as one of the “holy

minimalists”.

In spare dots on a page -- like graphic

art generated by a computer with a limited vocabulary, see left – the music

may have looked like very little . . . but it also sounded like little

which preceded it.

In spare dots on a page -- like graphic

art generated by a computer with a limited vocabulary, see left – the music

may have looked like very little . . . but it also sounded like little

which preceded it.

The austere beauty, almost weightless

quality of the 27 minute Tabula rasa -- with two versions of

Fratres (one for violin and piano, the other for a cello

ensemble) and the Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten – all

work on the album as an integrated experience, enhanced by Eicher's

clean but warm production.

In a much quoted piece from the on-line

magazine Salon in 99, the columnist Patrick Giles wrote of the

music's soothing qualities for those dying of Aids in 80s.

"Tabula rasa's relentlessly

severe, repetitive and deeply inspiring sound had a powerful impact

on my dying friends and their attendants. 'It sounds like the motion

of angels' wings,' a client whom I had a secret crush on once said.

“The music brought comfort to many of

us after we'd given up on the very possibility of it. People played

it at night, during meditation and, especially, when they were in the

hospital and feared they were dying. We had learned that even

patients in comas were still capable of hearing, and several people

with Aids requested Part on their death beds.”

And Part writes “the tonality of this

music has no mechanical purpose. It is there to transport us toward

something that has never been heard before.”

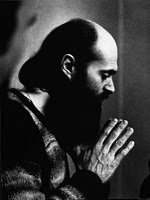

Part may look like a holy ascetic –

tall, stooped and heavily bearded like an Apostle in a Raphael

painting – but he is very much a man of the world and came to this

rare, spare music after decades under Soviet oppression.

As Alex Ross in The Rest is Noise;

Listening to the Twentieth Century noted, “References to him as

'monkish' miss the mark; behind his sad eyes and long beard is a

steely will. In 1979 he performed the un-Shostakovich-like gesture of

donning a long-haired wig and haranguing the Estonian Composers'

Union on the subject of official restriction. He defected to the West

the following year.”

Part composed 12-tone music as a young

man (“avant-garde bourgeois music” as the Soviet authorities

called it) but for 1968 his choral piece Credo he included the

provocative line “I believe in Jesus Christ” which angered the

atheistic authorities. It was a dramatically dissonant piece –

references to Bach juxtaposed with discordant 12-tone – and was the

last significant thing he would compose for many years.

However a chance encounter with

Gregorian chant and its emotional purity lead to immersion in that

music, and that of the early Renaissance. He found his way back to

writing and in 76 presented a piano piece Fur Alina in his

new, poetically spare style.

His music seemed driven by a holy

simplicity of expression more than the minimalist tag he has so often

been given, although in its sparseness “it's a cleansing of all the

noise that surrounds us,” as violinist Kremer has said.

And it has a restful, meditative

quality as those Aids patients in New York discovered decades ago.

But this is not music of death, rather

it is of life and reflection, and of transcendence.

As the title of Tabula rasa – from

the Latin, meaning “a clean slate” -- suggests, it is music of a

new beginning, life from silence and space. Just a few dots on a

score proving less is more. A rare kind of soul music where you can

hear the wings of angels.

And as Manfred Eicher discovered that

night, it makes you slow down and pull over. In every sense.

Tabula Rasa; Special Edition (ECM

New Series) is available in New Zealand through Ode Records.

post a comment