Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Consider these snapshots from his remarkable career: at the age of 17 he was announced to the world by his teacher, classical guitarist Andres Segovia, as "a prince of the guitar [on whom] God has laid a finger"; a decade later he was touring with Julian Bream; in '69 he was playing at Ronnie Scott's jazz club in London; there were rock gigs with his group Sky in the early Eighties; he was performing Spanish music in New York to sellout concert halls in '94; and a year ago he was exchanging musical ideas with the legend of Cameroon music, Francis Bebey.

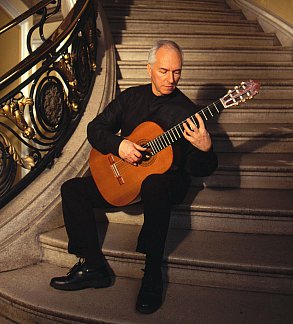

The public life of classical guitarist John Williams is too diverse to be easily encapsulated. Looking through the back pages of this 61-year-old's career there is a series of seemingly disparate musical images and a roll-call of famous names he has performed alongside: Itzhak Perlman, Andre Previn, Cleo Laine, Daniel Barenboim ...

Then there are things that don't fit within even the broadest parameters. His chart-topping theme to The Deerhunter (Cavatina) and music for the movie A Fish Called Wanda; recording with the Beatles' producer Sir George Martin; and appearances with the exiled Greek singer Maria Farandouri to protest at the military takeover in her homeland.

What is notable in this acclaimed career, which began with his first guitar at the age of 4, is how open Williams has been to music outside the classical idiom.

He has played with Spanish, Cuban, Paraguayan and Chilean groups, and most recently has touched down in Africa. Williams' latest album is The Magic Box, on which he performs with the late Francis Bebey on sanza (thumb piano).

Initially, his record company Sony

suggested he explore some African music ("It was a purely

commercial consideration for them," he says with admirable

candour) and a CD collection of stylistically diverse guitar music

from Madagascar, The Moon and the Banana Tree, pricked his interest.

Then, just as it appeared the idea wasn't working out, he encountered

singer-guitarist and ethno-musicologist Bebey, whom he had met

briefly 20 years ago in Paris. The magic started to happen.

Initially, his record company Sony

suggested he explore some African music ("It was a purely

commercial consideration for them," he says with admirable

candour) and a CD collection of stylistically diverse guitar music

from Madagascar, The Moon and the Banana Tree, pricked his interest.

Then, just as it appeared the idea wasn't working out, he encountered

singer-guitarist and ethno-musicologist Bebey, whom he had met

briefly 20 years ago in Paris. The magic started to happen.

"I'd heard bits of all kinds of African music over the years," says the chatty Melbourne-born guitarist from his home in London, "but I was never knowing what I was listening to.

"I loved African voices, and North African and Arabic singing, which is so different from the trained European voice. And I'd always liked instruments like the kora, thumb piano, balafone and so on. But it was only three or four years ago I started to become aware of the guitar element in African music."

Williams says that in sessions with Bebey (who died in May, shortly after finishing recording The Magic Box) he recognised that music from the continent is more sophisticated than his classical audience would believe.

"You see, it's not just rhythm, which is what you hear about so often, but the phrase lengths and harmonies that are wonderful, quite captivating in fact.

"Often people think of African music as, 'Oh yes, great rhythm and drumming, but what else is there?' Classical people just don't know what's there and so they pick on rhythm, the very thing that is underdeveloped or has lost its development in European music. They register what's missing in European music rather than what's unique about African music.

"African music is wonderful because it is polyrhythmic. We tend to think of rhythm in terms of dancers' feet on the ground. African rhythms have to do with arm, head and body movements and not just foot banging."

Williams also says classical musicians often believe that once they have mastered metre, and he includes himself in the generalisation, then that is all they need do.

"Classical people think once you play in time that's it, but the feel is something different and very tricky. Classical people can't feel how you sit back on a beat or play forward on a beat. Or for example in one piece we play there are groups of notes which fit into 12/8 time - but it is actually in 3/2/5/2 time which just adds up to the 12.

"Until I analysed it I didn't realise just how complex that rhythm really was.

"This music is very rich, and I don't think many people in the classical world appreciate that."

Williams, despite his extraordinary classical concert and recording career, has often irritated those who would want him simply to play works by long-dead composers. He still does that - he will perform in Athens with Cuban composer Leo Brouwer in March and do recitals and four orchestral concerts in Chicago with Barenboim - but his career is notable for his digression into jazz-rock with Sky back in the Eighties, which alienated his classical audience.

He admits Sky wasn't exactly embraced by the punk-friendly rock media of the time either. The only people who liked it were the hundreds of thousands who bought their albums and came to their concerts, he laughs.

"Obviously the older, traditional classical people didn't like it because they only like classical acoustic music.

"Fair enough. But there were a few of the young people into very down-to-earth street pop or rock who didn't like it because they saw it as a big record company doing something very commercial.

"And of course we were a cross-over collection of 30-year-old clever dicks and not 20-year-olds bashing away in the garage. But when we played rock venues like the Apollo in Manchester we had a fantastic reception from kids into heavy rock who had never heard anything like what we were doing, using harpsichords and so on.

"One day in Glasgow [Sky keyboard player] Francis Monkman played [18th-century Spanish composer Antonio] Soler's Fandango, the whole 13 minutes of it, and the place went wild. That gives you a thrill, and is worth more than 3000 people at the Royal Festival Hall clapping politely."

Of course that was two decades ago and since then much has changed in the music world.

Contemporary classical composer Philip Glass has worked with the African musician Foday Musa Suso, Paul McCartney has written an orchestral and choral work, audiences have become accustomed to world music through the agency of Womad concerts, orchestras commission work from jazz composers, and Elvis Costello has performed with the Brodsky Quartet.

It would appear the climate has changed to one of greater acceptance of musical diversity.

"Well, the general public has always been open to things. People who loved jazz 30 years ago still like jazz and everyone who liked blues and rock still does.

"And as to the so-called world music, the public hear it on television or on the soundtrack to a nature film or documentary, then they hear someone like [Senegalese singers] Baaba Maal or Youssou N'Dour, or they hear music of the Andes.

"The thing that's changing is die-hard classical people. They may be genuine music buffs but often haven't had the opportunity or been exposed to the wider world of music. But a lot more have now and they think, 'That's really rather good.'

"There are still those who think there's nothing as good as Mahler or Beethoven and they'll probably go to their graves like that. I think they're missing out."

And so, for the foreseeable future - at least two years and with a live album of their Afro-influenced music a possibility - Williams and his four-man group (which includes fellow guitarist John Etheridge, formerly of the Seventies progressive rock outfit Soft Machine, and jazz bassist Chris Laurence) will be bringing the sounds of thumb piano, trickling guitar melodies and mischievous polyrhythms to concert halls.

And Williams couldn't be more excited by the prospect. It will introduce a new sound to many people and, he hopes, open classical ears to other possibilities.

"The music scene has changed for the better and is continuing to change. And more and more those exclusively classical people will have to come to terms with it."

post a comment