Graham Reid | | 5 min read

In his final few years, Picasso painted over 400 canvases. Few people however would argue all these works were the equal of his early provocative masterpieces in the three decades after 1907.

Many were crass, scribbled daubs filled with self-referential jokes, and his etchings of time -- while remarkably assured in execution -- were filled with earthy sensuality bordering on the rude.

The last room in the vast chronological exhibition Picasso: Masterpieces from the Musee National Picasso, Paris, currently in Sydney, confirms at least some of that.

But even in his dotage, Picasso could surprise. The final work visitors see of the 150 pieces on display at the Art Gallery of New South Wales is The Young Painter, slashed out in what must have taken mere minutes on April 12, 1972, a year before his death at 91. It is a large work of a wide-eyed artist with a brush, the oily lines almost childlike in their spontaneous urgency. It's not a great piece, but reminds of what Picasso once said: “When I was child I could draw like Raphael, but it took me a lifetime to learn to draw like a child.”

Mission accomplished then, because the work takes you right back to the first room of the gallery where, as he said, he was gifted at drawing. The evidence is an academic study of a plaster torso done when he was about 12.

It is a small work, quickly overlooked by the passing parade of visitors, but the confidence of the shading and assertive outline are testament to his preternatural gift. But the subject and execution also reminds that Picasso – the son of a painter and art teacher – had been schooled in academic principles. And it was that which gave him his grounding, and something to recoil from and return to, as is evident in subsequent rooms in the exhibition.

Nearby is another juvenile work, a study of hands and a standing figure done a few years later, and already in the firmness of outline and a deep chiaroscuro which becomes an abstract block of form, you may see a direction he would explore, and which would change the course of 20th century art, and beyond.

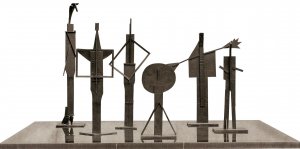

Of the 10 rooms of generously spaced

works – which include rough-hewn sculpture, tiny but precise

etchings, witty groundbreaking collages and some extraordinary

bronzes from the 50s of standing figures which refer equally to

abstraction and primitivism – it is the first, taking the artist

from Spain to Paris in 1905, which is given short shrift by many

visitors.

Of the 10 rooms of generously spaced

works – which include rough-hewn sculpture, tiny but precise

etchings, witty groundbreaking collages and some extraordinary

bronzes from the 50s of standing figures which refer equally to

abstraction and primitivism – it is the first, taking the artist

from Spain to Paris in 1905, which is given short shrift by many

visitors.

Some, in search of the blockbuster Picasso of Cubism fame, stride past exceptional works such as The Death of Casagemas, a 1901 portrait of the corpse of his friend who committed suicide where the vigorous impasto of paint shoveled on in the attendant candle flame acts as counterpoint to the gently sympathetic and smooth brushstrokes on the face.

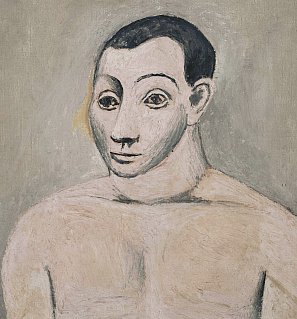

The famous Cubist works are out there, but here in the early years the ground is laid for the artist's journey through line, form and colour. The assiduous analysis, the searching eye and assured hand start to emerge in the second room in the bullish Self Portrait (1906) in which the solidity of form is pared down to elements. Of similarly reductive style nearby is one his chopped sculptural pieces in imitation of those “primitives” of Africa and Oceania which he explored in the Louvre, And alongside, from the same year 1907, is a study for his famous Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.

You can see the heroic abstraction beginning which will lead to revolutionary Cubism – but here too is a striking sense of colour in the discreet Landscape with Two Figures (1908) where planes of green suggest an autumnal reverie.

What this wide-swathe exhibition – possible because the Musee Picasso in Paris has shut its doors for renovations – offers is the grand sweep of genius. While not everything here taken in insolation would support that often loosely applied adjective – there are lumpy pieces alongside the breathtaking – what the chronology allows is an exploration of the artist's syntax of drawing and line translated into muscular applications of paint, and of an intellect in a constant state of working and reworking ideas in multiple disciplines. The survey presents the artist as macho bullfighter, not tortured soul (Van Gogh), prescient inventor (DaVinci), gifted charlatan (Dali) or pallid rock star (Warhol).

Picasso engages with life and form as a struggle, things to be deconstructed and analysed as in Man With a Guitar (1911) with its acute architectural analysis, or collages like the Violin sculpture four years later where the instrument is filleted and laid open like a frog on a dissecting board.

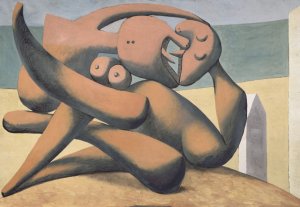

And in the third room (Cubism and

collage works) and the fifth (the large and striking surreal figures

of the decade from 1925 where the the body forms inflated and twisted

like balloon art figures) the pace of visitors slows and stops.

And in the third room (Cubism and

collage works) and the fifth (the large and striking surreal figures

of the decade from 1925 where the the body forms inflated and twisted

like balloon art figures) the pace of visitors slows and stops.

Here is where the familiar Picasso resides. Between 1910 and 1930 the tectonic plates which underpin Picasso – all that feverish drawing, analysis, line and colour – have shifted dramatically. Laid bare is the advance and retreat (his return to classical ideas and form after the horrors of the First World War), the thought translated into action, the rugged muscularity into rounded form . . .

Picasso certainly drew on others – the undeniable Goya connection in his Massacre in Korea of 1951 – but he constantly pushed and probed. He stripped back to essences and rebuilt, as in his deconstruction of Le dejeuner sur l'herbe of 1961, a century after Manet's original but now recast as contorted figures in a rather more unnerving setting.

Many works after 1952 seem more reflective and find the artist at rest, as in the colourful if sometimes mysteriously empty work from his studio in Cannes where the influence of Matisse is evident. Then there is that awkward and critically divisive final room where there are undeniable flickers of genius and technical skill, but in the service of what exactly? Some seem like the artist as randy but impotent old goat rather than the sexually voracious minotaur he preferred.

In most of the finest works however –

and there are more than enough of those – we see Picasso exploring

the human machine and the mechanics and architecture of its

construction, analysing the body's exterior and interior, or taking

apart objects like musical instruments and bottles, and bluntly

putting the calamities of humanity before us (there is nothing of

Guernica however to the disappointment of some). The survey admits to

the human failings of the artist by placing the gratuitous and

knocked-off alongside the more considered.

In most of the finest works however –

and there are more than enough of those – we see Picasso exploring

the human machine and the mechanics and architecture of its

construction, analysing the body's exterior and interior, or taking

apart objects like musical instruments and bottles, and bluntly

putting the calamities of humanity before us (there is nothing of

Guernica however to the disappointment of some). The survey admits to

the human failings of the artist by placing the gratuitous and

knocked-off alongside the more considered.

Interestingly, these works from across seven decades come from Picasso's own collection. From that schoolboy drawing and the blimp-like surreal characters on the beach to striking larger-than-life abstract bronzes of bathers and into that final room where the artist resorts to parody and humour (Behind the scenes in the picture, odalisque and painter from 1970 is a genuinely funny etching) and the childlike Young Painter, these were all works which meant enough to him that he wanted to keep them.

Of that problematic last room – a decade largely ignored in any discussion of Picasso's protean genius – the critic Robert Hughes once noted “late Picasso has great visceral power if not, necessarily, the magical efficacy he sought . . . and although these late paintings are not the best of Picasso . . . they are to be valued as fragments of the kind of talent that comes, at most, once in a century”.

There is an essay on Picasso's last self-portrait here.

Graham Reid travelled to Sydney courtesy of Tourism Australia, Destination New South Wales and Qantas

post a comment