Graham Reid | | 5 min read

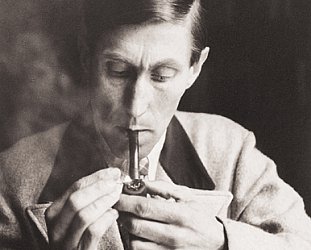

As a career change, it couldn't have been more dramatic or life endangering. In a few fast years Alfredo Bini went from being a factory manager in Italy to a freelance photojournalist being shot at by Gaddafi's troops in the Libyan uprising.

Bini was among the few journalists in Misratah and his photographs were the first the outside world would see of the nascent revolution which would eventually topple Gaddafi's regime. His award-winning images were the result of a journey made at his own expense when accompanying two journalist friends from Rome.

“We were a month in Benghazi then went to Misratah. There was no other journalists there other than someone from Al Jazeera,” he says from his home in the Tuscan town of Pistola as he packs his bags again.

“We took a car to Cairo, a plane to

Rome then went to Malta and got a fishing boat to Misratah. We stayed

for 36 hours but it was very dangerous. We were shot at two times,

the last time a mortar from the Gaddafi forces hit close to us. If it

had exploded I wouldn't be here to talk to you.”

“We took a car to Cairo, a plane to

Rome then went to Malta and got a fishing boat to Misratah. We stayed

for 36 hours but it was very dangerous. We were shot at two times,

the last time a mortar from the Gaddafi forces hit close to us. If it

had exploded I wouldn't be here to talk to you.”

Bini says before he made the abrupt career change, his photography had been of the kind most of us take when we travel or, as he charmingly puts it, “when I move my body”.

But almost a decade ago he began

attending regular workshops held by National Geographic in Tuscany

which brought in inspirational photographers like Bob Sacha and David

Doubilet.

But almost a decade ago he began

attending regular workshops held by National Geographic in Tuscany

which brought in inspirational photographers like Bob Sacha and David

Doubilet.

“I learned a lot in the workshops and every night we met with guys from other classes and spoke about reportage, glamour or fashion photography, or portrait work. So it was creative but also a learning thing for me.

“Before I had just done some tourism things, but this was like a call and I thought, 'This is my life and I want to try to be a professional at this'.”

Other seminars in Perpignan convinced him he would “look for stories that must be shown to people, and that's why I shifted from personal or landscapes to more political things.”

In 2006, Bini -- who still lives in his hometown of Pistola halfway between Milan and Rome -- quit his managerial position and threw himself into the world of geopolitics, corporate greed and gunmen. His most recent work has been on agricultural land grabs in Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates and now he is looking at covering mining land grabbing in South America.

But finding editors interested in the topic has been a problem. The crumbling economies in Europe mean money is tight and the issue has no immediate news hook. He also notes that even when issues are timely and he has images, some editors hold back and don't run the photos until a week or more after the event. If, as in the case of the Libyan uprising, they are capturing history and its victims then their immediacy is important.

It is not all guns and uprisings however.

He speaks lovingly of the island of Stromboli (right) where "I leave a part of my heart" and to where he frequently retreats, and he isn't above doing "commercial work" to pay the bills and support the other, more demanding life he has chosen.

He speaks lovingly of the island of Stromboli (right) where "I leave a part of my heart" and to where he frequently retreats, and he isn't above doing "commercial work" to pay the bills and support the other, more demanding life he has chosen.

In 2009 he embarked on an award-winning photographic exploration entitled Transmigration which was published by the BBC, New York Times, Herald Tribune and in European newspapers and magazines. It broadly addresses the African diaspora and specifically follows migrants through the Tenere desert in Niger.

“It's a story of migrants coming from West Africa and trying to reach Libya. After a year or two, if they were lucky, they might be able to reach Europe. To do this they use four routes and one is across west Niger. They moved to Agadez [to the south of the Tenere] and there they stayed a month waiting for the convoy. Then they move across the Tenere, which takes a week, and reach the Libyan border.”

Bini spent three weeks on the road with the migrants but says it was “a pinball political situation” as the Tuareg people were in rebellion and “the president of Niger didn't want journalists around”. “The rebellion was linked to uranium mining and that was a big issue. So I spent about 20 days hoping to get permission to move with the migrants. I didn't care about the rebellion. I would loved to have done something, but it was very difficult and that was another story.”

He was arrested twice and told to erase the memory from his camera: “But I didn't,” he laughs.

In many Transmigration photos the people look surprisingly happy and full of hope, despite the arduous and hazardous journey

“Yes, because for them it is the chance of their life. They are happy when they travel, they don't care about the sun, the lack of water and bad food. They are just happy because they are changing their life.”

Bini notes very few actually make it to Europe, most just wanted to reach Libya. At the time of his project there were 1.5 million African workers in the country.

“In West Africa they earn $30 to $35 dollars a month, but in Libya the salary is $300 to $400 a month. That is why during the Libyan uprising the migrants were on the side of Gaddafi, apart from the mercenaries.

“But in Benghazi or Misratah or wherever these people arrived, they were on Gaddafi's side because [Libya] was good for them . . . although there was corruption with the police and military, and some of them were incarcerated or put back to their country.

“But for the people themselves, the

reasons [to move] are no different than in the 18th and

19th centuries. In Africa everybody moves everywhere to

work, not just from Africa to Europe but from Burkina Faso they move

to Ghana to work on plantations. In Ethiopia girls move to UAE to

work as housekeepers, so for them it is normal. It is their daily

life.”

“But for the people themselves, the

reasons [to move] are no different than in the 18th and

19th centuries. In Africa everybody moves everywhere to

work, not just from Africa to Europe but from Burkina Faso they move

to Ghana to work on plantations. In Ethiopia girls move to UAE to

work as housekeepers, so for them it is normal. It is their daily

life.”

He laughs about how Europeans perceive these migrations

when they see “like, 150 people on a truck”.

“They don't do this because they are desperate, they move because it normal, just as it is to move from one town to another to reach a market. In Europe people see these pictures of guys on the truck and they say, 'Oh my god, it's bad'.

“But we had 13 people in one five-seater car, and on my trip back we were on a small lorry and there were 25 people. Just normal.”

For more on the work of Alfredo Bini visit his website here.

post a comment