Graham Reid | | 5 min read

The afternoon I arrive in Hobart to

visit the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), Germaine Greer is at the

Queensland launch of the Brisbane Writers Festival claiming half of

those in the state couldn't read a newspaper of follow the

instructions on a medicine bottle.

Twitterworld gets frenzied, writer Les Murray says he wouldn't “turn aside from a good urination to listen to Germaine Greer”, she makes the television news, and of course the festival organizers – director Jane O'Hara admitting inviting Greer because she would be provocative – are delighted.

Without Greer, most Australians wouldn't have known there was writers festival on. Tonight however . . .

As the careers of Madonna and Lady Gaga, and artists Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin attest, controversy is good for business. And Hobart's MONA – which has pricked art world mandarins and condescending curators protecting their corner, but delighted tabloid writers looking for shock value – is a gallery-cum-museum which obliges.

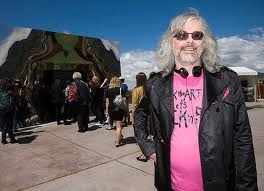

Conceived, built and owned by local boy David Walsh – pejoratively described as “gambling millionaire” because that's how he got stinking rich but “mathematical savant and philanthropist” might be more useful – MONA opened in January 2011 to publicity and controversy.

Among its hundreds of works and installations it's easy to single out push-button items: Ukrainian Oleg Kulik's large photo of a dog mounting a kneeling, naked man; Jenny Saville's enormous, beautifully decadent oil of a naked hermaphrodite with his vagina taking up much of the foreground; the torso remains of suicide bomber on the gallery floor with guts spilled out (rendered in chocolate by American Stephen Shanabrook) and Cloaca, a series of glass amphora connected by tubes and and cables, which replicates a digestive system.

In the shorthand of those wanting controversy, it's a poo-making machine

These are easily ticked off but of even greater outrage is the owner himself.

Walsh, 50, is an irritant to some in the rarified art world. A self-made man who doesn't care what they think and can afford not to. He buys and displays what he likes and, as a self-confessed secularist he likes sex, death and stuff that provokes. He's a master of the wind-up soundbite: he wants MONA to be “a subversive adult Disneyland” and considers formal curation “a form of mental masturbation”.

And much as some art plutocrats might want to make him a pariah, he isn't going anywhere. MONA – with a vineyard, superb restaurant, function rooms named Eros and Thanatos (sex and death), a brewery and hi-tech luxuriously eccentric on-site accommodation which earns around $A8 million and offsets the museum's running costs – is pulling in the crowds.

In a sniffy piece in Quadrant Online its editor Michael Connor, under the heading “MONA's Brutal Banality”, complained “the surroundings make the objects displayed into art” (true of any gallery perhaps) and said MONA offers “the art of the exhausted, of a decaying civilisation”

If so, many are curious to witness its demise. MONA has drawn more than 570,000 visitors since opening. MONA's critics say these people are not regular gallery-goers, but the same could be said for those at a Manet or Picasso touring exhibition.

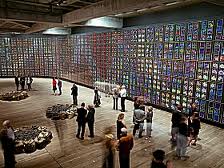

It's contents aside, MONA offers a very different gallery experience and is a breathtaking architectural achievement. The entrance across a tennis court subverts the notion of an imposing and often intimidating gallery and the 6000 sq metres of exhibition spaces are below ground on a peninsula in a working class suburb 15 minutes drive from central Hobart.

Melbourne architect Nonda Katsalidas had 60,000 tonnes of earth and limestone excavated so the vast subterranean galleries are hewn out of solid rock. Walls can tower scores of meters above or rooms can be compressed and claustrophobic.

Certainly there is typically tedious and pretentious video, the usual self-centred or trope-ridden mediocrities, and vacuous stuff which only survives courtesy of its push-button hereticism. Some of this is detritus and dull, but “Oh, look over there”.

There familiar names and works here

too: Picasso's Weeping Woman; a hand-coloured photo by Hans

Bellmer; a figure by Francis Upritchard (one of this country's

artists at the 2009 Venice Biennale); a mundane Damien Hirst's

dabstract; a loop of the controversial eye-slitting scene (of course)

from the Luis Bunel/Salvador Dali film Un Chien Andalou . . .

The cavernous space has allowed for Sidney Nolan's 46m Snake, a nine metre high, of 1620 separate painted images of Aboriginal faces. Here too are a fine Brett Whiteley, Julius Popp's hypnotic installation where words appear briefly in a waterfall of droplets, a silent space given over the Wilfredo Prieto's library of all-white books and, most impressive, a room – the size of three squash courts – of tapa cloths, many of them from the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery with whom MONA has a symbiotic relationship and shares works, and from which it has poached staff.

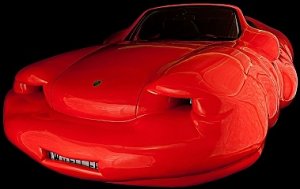

Art at MONA is deliberately decontextualised and recontextualised in a way – like Te Papa – that perhaps offends more orderly curatorial precepts: a bright red Porsche inflated like a balloon is beside an Egyptian sarcophagus.

Some associations make sense (Picasso the primitive near Aboriginal artifacts) and the large cabinet full of disparate objects – a porcelain bust from China, brain coral and an 18th century Japanese erotic scroll among them -- might act as metaphor for MONA where work is displayed for its own sake and distinctiveness.

MONA is like a massive underground cabinet of curiosities.

MONA's critics are obliged to perform intellectual gymnastics about it: the coterie which would argue art should provoke, create discussion and even invite us to consider that knotty question, “Is it art?” don't want to engage in that discourse with Walsh because, you suspect, he isn't one of their own and has done all this himself. “Is it Art – or Exhibitionism” ran the headline in Britain's Sunday Times Magazine when debating such extravagant privately-owned museums.

Some in the art world have complained about the lack of attribution or explanatory notes beside the objects and art, ironic that critics and the cognoscenti, those least in need of having their thinking directed, want crib-sheets.

In his hilariously heretical book The Painted Word, Tom Wolfe observed, “Modern Art has become completely literary: the paintings and other works exist only to illustrate the text”. True, as many curators essay inexplicable and often inane, unworthy works into life.

But MONA doesn't leave visitors adrift.

An innovation which other galleries might consider is “the O” provided free on entry. A touch-tablet the size of an iPhone, it holds details of the work, some “art wank”, amusing or provocative comments, the artist in conversation and such. If you register your e-mail address when you get home the art you have seen (and a link to that which you missed) is available to you through MONA's website.

Love it or find it offensive, MONA is pulling in crowds, has brought international and interstate tourism to Hobart and is downplaying a little the controversy which attended its opening (although you can still by the vagina-shaped soap in the excellent bookshop-cum-store).

It is on this year's Conde Nast Traveller “hot list” and is fascinating, problematic, laugh-aloud and thought-provoking.

It's also a unique and audacious conceit by Walsh (above) who at the opening exhibition – in a blokey, funny and blunt line might appeal to Les Murray – told a local paper, “The museum is my soapbox and I've got one hell of a microphone”.

post a comment