Graham Reid | | 6 min read

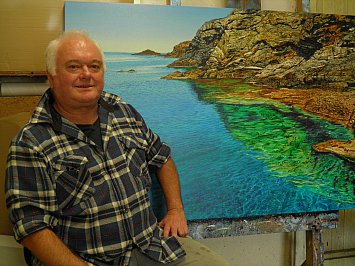

Odds are Mark Cross was among the oldest in the audience at the recent concert by American nail-hard metal rockers Tool. And probably the only artist.

More than a decade ago he heard Tool's Enema and was taken by the lyrics “I'm praying for waves . . . flush it all away . . . learn to swim” which related to conversations he was having with the American writer Brad Matsen about cycles of species extinction.

Taken together they lead to Cross' large painting Global Enema (Noah's Extinction Event) in which a Poseidon-like figure – Matsen – seems to be rising from clear blue water.

Rendered with Cross' distinctive eye for realistic detail, the work has a powerful political subtext, as with his earlier Oppenheimer with its reference to nuclear weapons and Leaf Gatherers in the Season of Entropy about fossil fuels.

Elsewhere in Cross' back catalogue of almost 30 years are images of the striking rock formations of Niue where he has long had a home and studio, stark landscapes which may -- or may not be -- the Kaipara near his home in Riverhead, and mysterious works which straddle the borders of realism and surrealism.

A decade ago the Herald art writer T.J. McNamara wrote Cross was “New Zealand art's most gifted outsider”, a description -- even now -- which he accepts.

“I do actually, because I'm not on the inside,” he laughs as we sit in his Riverhead studio before a new work destined for Pierre Peeters Gallery in Parnell. The gallery is his sole representative in this country and he joking refers to it as a “transit point” before his paintings go off European art fairs, galleries in Zurich and Mykonos on Greece, or into the hands of private collectors.

“I've never been taken up by [the art establishment], mainly because I'm self-educated and haven't come up through the networks and university. So I missed the boat there. There's a price you pay for that, but also because I haven't been I'm far more free and paint whatever I want.”

Cross says he recognised long ago that New Zealand art history was mostly lineal, one artist building on a predecessor, but the increasing acknowledgment of Maori and Pacific artists made people realise there were other traditions running parallel.

“I'm like that.

“I'm like that.

"I'm an outsider because I work parallel to the mainstream, although I have drawn from some of the old masters, traditional European art and some contemporary stuff.

"But everyone who's ever written about my work has always been way off track.

“I think New Zealand art is predisposed to a desire to create an identity whereas they've tried to read my art in the same way. It can be done if it's a New Zealand landscape, but my ideas are universal and any identity aspect is incidental.”

He notes a figure in one of his works was described as Polynesian, “but the model was Finnish. Because I live on Niue they think all my figures are Niuean. Those that realise I'm not coming from some kind of introspective cultural identity angsty thing just ignore me because my intention is more universal than that. That's the sense I get”.

“Identity should be a means to an end and not an end in itself. The identity should come thorough in the art and not by stating the obvious.”

A trained toolmaker who worked in an engineering shop but always painted for his own pleasure – “ adolescent surrealism but they have a realistic rendering of sorts” – Cross taught himself by looking at art in galleries and by doing it.

When he married Ahi from the village of Liku on Niue, he went to the island in 78 at age 23 – “it was more basic then, but there would have been 3000 people which is more than twice as much as today” – and, over the four years he was there and teaching himself art history from whatever resources he could find, like so many was struck by the powerful density of the forest, the clarity of the unpolluted ocean and the light.

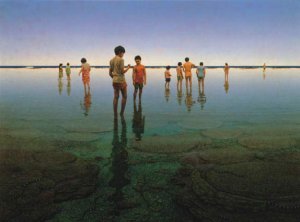

Whereas his juvenilia had been pulled from his imagination now he had concrete images to work from which stood on that boundary of surrealism and heightened realism. Although he continues to paint landscapes (often from photograph he manipulates or introduces other elements into so they are not literal), paintings with figures have often consumed him.

“With landscapes you need half a

dozen as a series to show people what you are trying to get across

but paintings with figures can be one-offs. I think one of my better

figure paintings is like an exhibition in itself. I can only manage

to do one a year because they take so long.”

“With landscapes you need half a

dozen as a series to show people what you are trying to get across

but paintings with figures can be one-offs. I think one of my better

figure paintings is like an exhibition in itself. I can only manage

to do one a year because they take so long.”

Dividing his time between his homes in Riverhead and Niue – usually eight months on the island although he can be more productive in Auckland – may sound glamorous but he admits each place can be claustrophobic in its own way.

“In Niue we're in the bush and here we've not got much of a view, and I like the arid places as opposed to the rainforest. This is a respite from that and when I'm here I go to the Kaipara because you can see a long way. Except for looking out at the ocean in Niue you can't see distance.”

A keen cyclist – “I get bored with cycling around Niue though, and here I'm scared of traffic” – he joined a group five years ago for some pedaling in western China and then on the 13-day route from Lhasa in Tibet to Kathmandu.

“I was in a constant state of altitude sickness,” he laughs, “but I'm thinking about my work. It gets mundane but in terms of plodding on it's a good discipline. It's the same with my work, it's a bit of a grind at times.”

Some of the landscapes he photographed

on the journey may be making their way into paintings, just as lava

fields in Hawaii and the Kaipara Flats have . . . but which are used

in a way which again belies their geographical specificity.

Some of the landscapes he photographed

on the journey may be making their way into paintings, just as lava

fields in Hawaii and the Kaipara Flats have . . . but which are used

in a way which again belies their geographical specificity.

He says hours at the easel isn't good for the health which is why he does “other stuff” like establishing a sculpture park at Hikulagi just south Liku on his wife's land.

In the Fifties and Sixties an area of land was cleared by New Zealand agricultural experts to grow kumara but the project failed and after using it for a lime plantation he too let it go.

But in 95 he, the sculptor Mikoyan Vekula (now living in Wellington), the late Charles Jessop and others formed a collective to use the land as a canvas.

Vekula has a circular totemic work installed, Cross a large and growing installation, and this year to coincide with the island's biannual arts festival, they ran a sculpture competition for children (“get the kids involved and the community's involved”) and all-comers.

The youngest winner was 17, the all-comers winner was 70.

Recently he has also begun making his own lo-tech films which have specifically concentrated on Niue.

One is a time lapse film of the creation of Leaf Gatherers in the Age of Entropy in his Liku studio, and Language of Moths shows his attempt to write at night while being battered by hundreds of moths attracted by the lightbulb and with music by the group Set Fire to Flames helmed by guitarist David Bryant of the Canadian post-rock band God Speed! You Black Emperor.

"I bought that piece of music years ago

and tracked him down and said I couldn't pay but I'll look after you

if you come here – or Niue! – and sure enough God Speed! Came

here.

"I bought that piece of music years ago

and tracked him down and said I couldn't pay but I'll look after you

if you come here – or Niue! – and sure enough God Speed! Came

here.

"So he took us up on it and had heard of Allan Gibbs' sculpture farm, so we got permission and I took him and violinist Sophie F. Trudeau [of God Speed and A Silver Mount Zion] there.”

Two others films have music by Auckland composer Darryn Harkness whom he met on Niue: “Up there you grab any artist who passes through.”

The films may be entered in competitions, but Cross – painter, sculptor, experimental film-maker – says he's not attached to that idea, or whether he will ever be anything other than that gifted outsider.

“I worried about it for years, but the older you get the more you reevaluate why you are doing it.

"For the next 10 or 20 years it will be about taking my art where I want to travel.

"Hopefully it will pay for the trip,” he laughs.

“Musicians do the same thing in a way.”

Mark Cross' website is here . . . and be prepared to be surprised and seduced by the breadth and depth of his ideas and art. Many of the works mentioned here are pictured.

The link to his work at Pierre Peeters Gallery website is here. There is an excellent and intelligent interview with Mark Cross here.

post a comment