Graham Reid | | 19 min read

2020 is the 100th anniversary of Ravi Shankar's birth and although tributes had been planned, most have been put on hold. We repost this [ and this personal essay] as our tribute

.

The apology couldn’t be more profuse. Three times Sukanya Shankar giggles self-consciously and says, “It's my fault,” each time following it with a litany of “sorry, sorry”.

She had forgotten to tell her husband of this appointment, she says, and now he is teaching in the music room of their secluded home in the hills of Encinitas in balmy southern California.

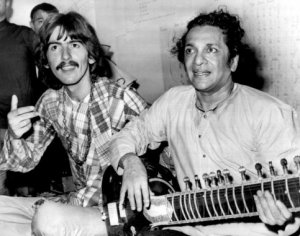

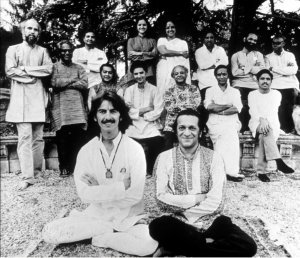

And when Ravi Shankar -- composer, sitar master and, according to his longtime friend George Harrison, “the godfather of world music” -- is finally available he is equally and embarrassingly apologetic.

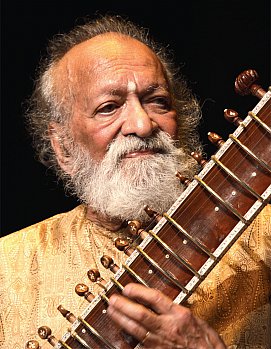

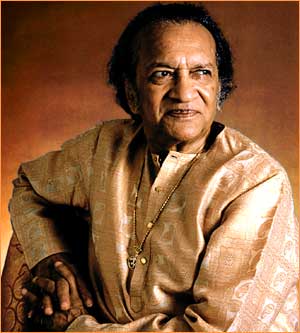

Polite, alert, mischievously and modestly tweaking his reputation as one the greatest classical musicians of this century (and some would say lndia's finest ever), Shankar is active and, despite recent illness, continues to play.

Despite his popularity in the West -- elevated by his collaborations with Sir Yehudi Menuhin, various jazz musicians and notably in the late Sixties his high-profile friendship with Beatle George Harrison - Shankar is an avowed traditionalist and takes his teaching role seriously.

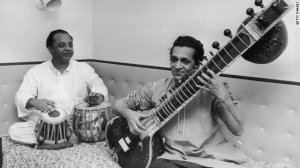

Shankar's own regime as a student under Ustad Allauddin Khan in the Thirties involved study and practice 14 hours a day, celibacy, meditation and fingers which would bleed after hours of playing the steel strings of the extraordinarily complicated sitar.

But that prepared him to take the instrument and his compositional skills to previously unheard of popularity and artistic heights. Yet the honours bestowed upon him (a dozen honorary degrees among them), concerts everywhere from Woodstock in the Sixties to the Kremlin in the Nineties, and the public and professional acclaim for over five decades seem to have barely affected this diminutive (159 centimetre), self-effacing genius of classical music.

Heart problems have plagued him and the natural attrition after a life of travelling and performing has taken its toll. And there is a visible symmetry to his life being established.

Two years ago, with Harrison as executive producer, he released the handsome In Celebration, a four CD retrospective collection of his work, then last year recorded Chants of India, his acknowledgement of the traditional vocal music of his homeland.

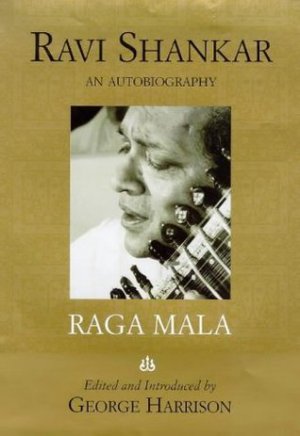

And this year his autobiography Raga Mala has appeared under the Genesis imprint in a limited edition of 2000 copies, each of which comes on acid free paper, signed and individually numbered, hand bound in Indian silk, in a large custom crafted box and with a four track CD and a box of Shankar's favourite incense.

It is a magnificent set but the more

remarkable for the story it tells.

It is a magnificent set but the more

remarkable for the story it tells.

The youngest of five sons born into an upper caste Brahman family in Varanasi, he grew up in parsimonious circumstances as his father -- a scholar and later lawyer practicing in London -- left his mother before his birth.

It was his older brother Uday who broke with tradition and studied painting at the Royal College of Art in London. On his return to India in 1929, and encouraged by Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova, he put together a troupe of dancers and musicians which included the nine year old Ravi. The following year they began performing in Europe and the States.

In the subsequent years the musically and, by his own admission in Raga Mala, sexually precocious, Ravi met Pablo Casals, Stravinsky, Segovia, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Count Basie. Turning the pages on his early life it is like reading some curiously Indo-version of the Jackson Five.

In his pre-teens he drew favourable notices for his dancing but at age 14 on a visit to India he met Ustad Allauddin Khan who, the following year, was to become his sitar teacher.

After the luxurious life of hotels in Paris, London, New York and Hollywood, the teenage Shankar started seven years in India under the stern tutelage of Khan, married his teacher’s daughter Annapura (an unhappy marriage during which he admits to various infidelities) and in the late Forties began composing film scores and working on All India Radio.

From there his story is better known: the soundtrack for Satyajit Ray's Pather Panchali brought him to international attention, he toured Europe and the States extensively, then in the mid Sixties met Harrison and unhappily found himself performing before stoned hippies, and reviled back home for allegedly having sold his heritage for an audience which knew so little about Indian classical music it applauded him when he tuned up (at the Concert for Bangladesh in 1971).

He retreated from the raga-rock crowd in order to reconnect with his home audience, continued to bridge the cultural divide between West and East through concerts with Sir Yehudi Menuhin, was nominated for an academy award for his music for Attenborough's Gandhi in 1983, survived a quadruple bypass in l986, worked with minimalist composer Philip Glass . . .

A remarkable life recounted in detail and -- with regard to his obvious numerous infidelities and love affairs -- discretion in Raga Mala.

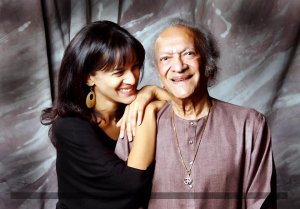

You were teaching then, your daughter

Anoushka, for how long every day would you do that?

You were teaching then, your daughter

Anoushka, for how long every day would you do that?

We had an evening sitting, usually for two hours, two and a half hours. Sometimes it's the morning, sometimes afternoon.

But every day?

As often as possible.

I won't ask if she's a good student, but are you a good teacher, a patient teacher?

(Laughs) Yes, if the student is not . . . dumb or slow. You know what I mean? I can be very bad and angry and a terror to my students if they are not quick in picking up.

Do you have many?

I have many. One of my oldest students died recently, I think he was 80 or something like that.

I know that the teaching tradition where the teacher is more than just a teacher but a mentor, as you had with Ustad Allauddin Khan, seems to have broken down a bit in India.

It is bound to because the world has changed. Before it was a completely different ambience. All the great masters were attached to princely courts and smaller places away from big cities and they were not at all worried about money or anything . . . so they took their students according to their liking, if they were really very talented, were of their own family, relatives or outsiders, they could pick and choose and it was on their own terms.

There was enough time, not this hurry and rush, it was a completely different ambience. Today with those princely states gone, no sponsorship, the musicians are all in large cities and they are all busy either giving tuition or performing or whatever, and the students have to live on their own and there are no more . . .

Before they didn't have to worry, they would just stay with their guru and they had all possibilities without thinking of earning money or the economic conditions or whatever, and their parents gave them away sort of thing. They didn't think of having to earn money for their family or their parents.

Today because of all these problems it is quite a different thing. Basically that feeling for guru and the love for students, of course, has remained to quite a large extent.

I imagine too it is quite different now for teachers also. In times gone past in those principalities or whatever would have been supportive. Do you feel because of your unique position it is a responsibility of yours to be a teacher as much as a performer?

For any performing artist -- if he’s wanted or in demand, there's nothing like the addiction -- whether in West or East it is the same story. As long as he is in demand and giving a performance which is pleasing to the audience, he gets programmes and I think he likes that as the best thing, which is natural.

The second thing or choice is a duty, when an artist is not able to perform like they could, or is not so much in demand they have much more time and they naturally divert their energy to teaching much more.

I know you are a man who always seems

to have projects you are working on and I also know you are touring

reasonably regularly, recently playing with Ravi Coltrane at a

concert. How much touring are you doing at the moment?

I know you are a man who always seems

to have projects you are working on and I also know you are touring

reasonably regularly, recently playing with Ravi Coltrane at a

concert. How much touring are you doing at the moment?

Not as much as I was doing before because travelling has become such a hassle now, not like what it used to be. So I pick and choose my programme. By God’s grace I get a lot of invitations but I don't pick as much as I did before. But still I would say the ratio would be two or three programmes a month, sometimes less and sometimes more.

And how is your health today?

By God’s grace I am alright, considering what I have gone through. At my age now, I'm 78, I am thankful to God for that.

I'd like to talk to you specifically about the autobiography you have written. You wrote this and at your age, with all due respect, it might have been more comfortable if you had had somebody write it. Why did you feel the need to do it yourself?

I had written two books earlier which were not purely autobiographical, one is quite well known, My Music My Life, but that has more to do with music and the music in my life and I talked more about the tradition. The second I wrote in Bengali, my mother tongue, and that was also partly my life story but it was again more talking about a lot of musicians I have met in my life, particularly Indian musicians and people from my childhood . . . and it was my feeling for them and a tribute to what I felt.

This one came at a time when I was requested by this publishing company Genesis who conveyed it to George Harrison. They have done different things on many people including the Beatles and George's life so it came via George and his request I should do this.

And that's how it happened. (Laughs)

I recorded and taped, wrote in free-hand myself because I cannot type, and also dictated a lot to Oliver Kraske.

It is a remarkable story but what also surprised me is how candid you are, yet discreet about personal matters.

A very difficult job. I have written how difficult it has been, because when you are asked to write about personal things and how much it can hurt others yet at the same time keeping all that in mind, it was quite a difficult job. But you know it says in the introduction in Hindi, 'samjhdaron ke liye ishara hi kafi hai', which means “a hint is enough for intelligent people to understand.” I've tried to maintain that.

Your personal life seemed to be remarkably complicated at times!

(Laughs) I don't care about my being maligned or saying anything bad about myself, but I have always tried not to do that for others. I was not interested. This could have been a sensational book if I had wanted to write al the all the, you know . . . (Laughs)

Today the trend is, to sell the book is . . . That is not something I appreciate really.

But it seems almost from birth you were in quite a unique position between East and West, members of your family. Did you at any time feel chosen because you were comfortable in both worlds?

It‘s strange you say this because this my incentive, being able to do all the things I wanted to do, and most of the things I have not been able to do yet! Whatever I have been able to do is this thing you have said, I took the responsibility on myself because I knew that maybe I could do it, more than anyone at that time. Of course later always you find people learning and getting ideas and they can do it.

Today things are different and there are a lot of Indian musicians who are very well educated, even more well educated than myself, who are diplomats and know languages.

But at that time when I was coming up and became fairly well known in India, I didn't find anyone who had that much idea who could communicate.

So I took that thing. Whether you use the word chosen or whatever, I felt I could do it and that's something that has been in most things I have done.

When everything was going very well,

while there might have been some misconceptions about it in Europe or

the United States . . .

When everything was going very well,

while there might have been some misconceptions about it in Europe or

the United States . . .

I can‘t help that, you know. Whenever you think something is seen in a new light or try to show something for the first time expressing things, it's bound to be criticised by people who are old timers or think like traditionalists.

But coming back to the point you said just now, I am a very strong traditionalist myself and I have been through this training of the tradition every way: religion, music, our culture, our heritage, but because of my childhood it was blessing to have my eyes opened before even I became fully grown up.

That gave me both sides, which is not very common I think. Because most of the musicians even today they have come out after they have grown and been educated in India, and see everything in a different manner than I did.

I was so lucky coming out at the age of 10 and growing up mostly outside and going to India again and again in that period.

I imagine it must have hurt you quite a lot that so much criticism came, say in the late Sixties, from people in India who didn’t understand what you were doing? That must have hurt more than hippies smoking drugs at concerts.

Absolutely so. You really are very sensitive because that is one point which I have always made all my life. Along with all the respect and admiration, I have always seen -- mostly from India of course --people who are envious and jealous and that came from the musicians and, what is the word, sycophants and their admirers. And they built up a such a strong propaganda and were saying things which were not true actually.

They took certain points like saying I don't play any more the pure Indian tradition because I just give a performance for only two hours, and I played ragas very short. That was a big point to them, but these are all such childish things because all our great musicians made even three and a half minutes records or performed on radio for 15 minutes.

So it’s not by the time you can evaluate this tradition. And we have different styles of presentation starting with the very strictly traditional style which I was lucky in having been initiated in, and was so spiritual and very traditional.

But along with that there are different forms which are very much contemporary and have improvisation but are adding new things, which has always been done. And because things are speeding up so much now, all of that has gone.

What you have said really -- the worst thing was in the late Sixties and early Seventies, but today there is no problem.

Also I did many things before the time. It sounds . . . I'm not bragging about it, but doing music for film for example or doing stage work or whatever I did, it was not appreciated then, but now they are. So I feel quite grateful about that.

I thought it was interesting your response to that criticism from India at the time: you could have entirely ignored it, you could have carried on doing what you were doing or gone away and made a million dollars being a guru to the stars -- but you actually felt the need to prove again to your home audience that you were serious and arduous concerts. You always felt the need to have acceptance from India?

Yes, I went through a period of being very hurt and wanted to prove myself to them and that I was not a goner completely. (Laughs) So those years I really gave to them what they wanted! Really killing myself playing for seven or eight hours programme, the whole night, something like that.

You also seemed a bit hurt that the music you wrote Sare Jahan Se Accha, you hadn’t received acknowledgement for having written that.

That was the most stupid thing I have ever done, not only that but also regarding many new ragas, because I was so . . . In India by nature we don't have that copyright system and having been in the West for so long I should have known better. And I never had anyone who could give me the proper advice and because I had no home, for years and years I was travelling, the problem was I was completely enjoying the fame and name and everything and being inspired - but I never took care of all the business things like copyright.

Nowadays there is a new thing -- you might even read in e-mail, or in Yahoo or whatever -- a lot of stupid things coming out with some youngsters saying I am trying to claim this, but that it's not true. Like if I say that is my tune.

Anyone who doesn't know wouldn't know, but as far as that is concerned no one is raising any questions . . but regarding some ragas I did as original conceptions -- and it's very likely because all permutations of combinations have been done in the past.

And they are all written down but they are just notations of ascending and descending, or you find them in Sanskrit books or some place like that and there are different names . . . So we are not supposed to know thousands and thousands of ragas. Anyone who conceives a new pattern it is likely it could have been done before and belong to some people a couple of hundred years before. But as far as you are concerned you think of it as something new and you give it a name.

But nowadays there is this whole thing going on trying to challenge people. I don't blame them, but this s typical of our people.

It's interesting what you say about

things being known hundreds of years beforehand. I was interested to

read in your book George Harrison saying when he first put on a

record by you that he felt he knew it. I've had that experience with

Moroccan music, it was just so familiar to me the first time I heard

it, almost like music I knew from before I were born. Do you feel

that people have been here previously and so recognise these things

from before?

You are talking about reincarnation or something like that?

Maybe that, but more perhaps a

collective unconsciousness.

Maybe that, but more perhaps a

collective unconsciousness.

Yes, but do you not agree with me we find that in so many things, like this whole deja-vu thing? We are experiencing quite often these things. I do it so often I am amazed, although I am not amazed anymore. (laughs)

Things seem to me to be something that we know, like the repetition of the whole thing. So musically also I am sure it has something to do with previous, whatever you call it, paths or the soul having known about it.

I know you've always made a clear distinction between the improvisation in jazz and that in Indian classical music -- but you’ve also worked with many jazz musicians. I know too that when you've done the West-meets-East things it has tended to be in the classical idiom. Did you ever see the jazz thing opening up more. You did things like the improvisations on Pather Panchali with Bud Shank, that was an area which seemed to me full of potential.

The biggest thing I ever did was in India in a jazz festival and there is a record, I wonder if you have heard it, Jazzmine.

I read about it but haven't heard it.

I wish you could hear that because John Handy was there and other famous people, and some of the good jazz musicians who are in Bombay and I did the whole thing connecting jazz and classical and folk. What I wanted to show was that in our folk music we have a lot of jazz elements also, especially in the excitement parts with rhythm parts and drum solos.

It seems an area which remains largely unexplored.

I wouldn't say that. Everybody seems to be doing that these days! There are fellows in Germany and France and the New York area and California, and before it was mostly local people, English or American. But now Indians are doing it a lot and some of them are quite interesting

I find it so, but I've not been deeply moved by anything yet. It seems a bit too gimmicky than actually something which would last. With the present tendency everyone's trying to make money and sell records, that's the main thing. And get a Grammy award.

Everyone is going out of the way doing things and sometimes they are lucky and something nice comes out, of course. But most of the time it's very gimmicky.

Do you feel that too much today people

are aiming at the world of recording than of playing the music live?

Do you feel that too much today people

are aiming at the world of recording than of playing the music live?

To tell you the truth, money has become the big issue naturally. Everybody wants to make money, whether it is by selling a book (laughs) or a record or having programmes with a very high fee. But that has always been there with any famous singer or classical musician or opera singer being treated like superstars. But they can never compete when it comes in the comparison to Michael Jackson or the Beatles or Madonna.

Pavarotti might be making maximum money in the classical field, but he has almost become like a pop opera singer, you know?

So that is the one thing which is the incentive of many people who are trying to do something new or maybe make like [undistinguishable] was very lucky someone put him in a film because he was singing for quite a long time.

But this little thing with Peter Gabriel or what was his name? That film did the trick and he became like a superstar. I myself can say that it really was George Harrison's connection with me which gave me a big push to become so popular with the young people in those days. It did help,

I admit about it, I'm not ashamed to say it. But I fought it and was not swayed by it and through that I kept my integrity and the music pure, and that's why I am where I am today.

Otherwise it would be the same story as all these pop stars, sometime it is one year, sometimes two years, sometimes 10 years. But only true people like the Beatles are the lucky ones to have really existed for so long. .

That's the big difference between classical music and pop people.

When you reflect back on your life are

there any unrealised ambitions? Any music you would like to have

made, any areas you feel went unexplored?

When you reflect back on your life are

there any unrealised ambitions? Any music you would like to have

made, any areas you feel went unexplored?

Honestly, I am so crowded in my head with all the ideas and new things.

My great ambition, and I've done one only in about the last 10 years, it was a theatre drama ballet with songs of operatic nature, and it was a great success for the touring opera company. And I had it also done in India.

These are the things I love to do, a big production with a mythological aspect of truly Indian subjects. But this is a difficult area and naturally it is very expensive.

And stressful?

Stress is not the point though because when I am inspired I feel healthier. But, if I were 20 years younger -- because you have the energy to talk to people and get things done. Now I don't have the energy to do all that.

I am going to have to put this delicately, but you have written your autobiography, you have released the retrospective In Celebration set of music and the Chants of India album which is your acknowledgement of the past and the tradition . . . are these thing the full stop at the end of the life of Ravi Shankar?

Not as far as I am concerned. My faith decides that, that's a different thing. As the saying goes, I am full of beans and ideas and I'm having a new recording because the recording company is interested and many things are going on. I have been offered many things for the millennium and some guitar concertos and I just finished a piece and sent it to Rostropovich. He‘s so happy, he wanted me to write something for him so I wrote a cello and harp sonata.

I am as active as ever, but need to be inspired and not do something for the sake of it.

So the work goes on?

So the work goes on?

Yes (laughs) Are you speaking from Sydney or Melbourne?

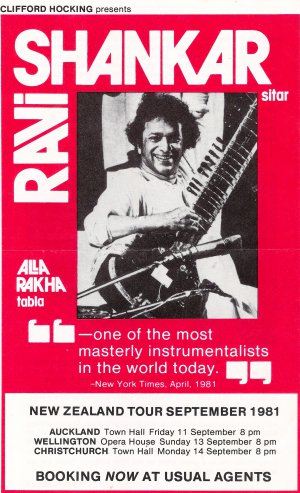

No, from Auckland, you played here last in 1981 at the Town Hall.

Oh, Auckland. I love that place.

You remember Auckland?

Sure, and Christchurch and Wellington and Dunedin.

Dunedin was the southmost part I‘ve been (laughs). I really love that country.

Hell, we wish you'd come back.

Oh I hope I will, I love that place. And Sydney and Melbourne, especially these two cities.

Of course Perth is very beautiful, but you are from New Zealand which is another place. (laughs)

I shouldn't hold you up any more because you have been very generous with your time, but there are a couple like to say. First, thank you very much for the music and the pleasure you have given me in my life . . .

Bless you and I hope we meet some time. You know you can keep in touch with me anytime you know, if you have any other questions or . . .

Thank you, and

can I also say thank you for I Am Missing You which is one of my

favourite songs of all time, so simple and eloquent. I'm delighted

you put on the CD which comes with your book. You wrote that on a

plane in 1967, a difficult year for you, and I wonder what mood would

have prompted you to write such a yearning and beautiful song at that

time?

Thank you, and

can I also say thank you for I Am Missing You which is one of my

favourite songs of all time, so simple and eloquent. I'm delighted

you put on the CD which comes with your book. You wrote that on a

plane in 1967, a difficult year for you, and I wonder what mood would

have prompted you to write such a yearning and beautiful song at that

time?

I think we were travelling somewhere in the States and I just had this feeling that . . . Maybe just for fun writing a song in English. I have written a number of songs in English and never taken them seriously. We were planning a record at that time for George to produce the Music Festival From India and Shankar Family and Friends [albums], and it was very short, maybe six or eight lines. It came very spontaneously with the tune and I noted it down.

Sometimes the beauty is in simplicity, isn't it?

Exactly. And this is something I have always believed.

The simpler way can stir the heart, whether musically or on sitar. You know, with a lot of curry powder you can cook, but to be able to cook something very simple with almost no ingredients, the way the mothers or grandmothers would cook in the olden days, is much more tasty than anything the best chefs can cook.

Thank you very much for your time and may I wish you health and happiness for the rest of your life.

Thank you. What is the time there in New Zealand?

It's about quarter to four in the afternoon.

Hmmm, are you sure it's quarter to four - or three thirty?

Now that I look it's just after three thirty.

Yes, I thought so because here it's just after 8.30 in the evening.

You are right again! So thank you for your time and best wishes from here.

Thank you and God bless you. Good bye.

Pandit Ravi Shankar died in December 2012. He was 92. His daughter Anoushka Shankar is interviewed here. Another daughter Norah Jones is interviewed at Elsewhere here.

2020 is the 100th anniversary of Ravi Shankar's birth and although tributes had been planned, most have been put on hold. We repost this [ and this personal essay] as our tribute

.

Mike - Aug 20, 2013

Whoa - Indian Blues! Great interview.

Savepost a comment