Graham Reid | | 5 min read

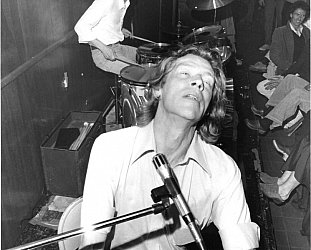

Douglas Lilburn: Winterset (1976)

Here's an odd, post-modern idea for an episode of Doctor Who.

The good doctor finds himself in London's BBC Radiophonic Music Workshop in 1963 where techno-boffins are fiddling with primitive electronic equipment. They're creating a distinctive piece of music to be used for a new television series called . . . Doctor Who.

And who should also be there but New Zealand classical composer Douglas Lilburn.

In Doctor Who's bizarre world of fantasies this is not impossible. In fact Lilburn – then on a study sabbatical – did actually visit the electronic studio around that time, although later noted it offered “a no-welcome sign to composers”.

Whether he heard that famous Doctor Who theme music is uncertain, but Lilburn certainly returned to New Zealand a changed man for his time in electronic studios in Canada, Germany and Britain. He established the first Electronic Music Studio at Victoria University and devoted the rest of his composing life to electro-acoustic music, a giant leap for the man who had composed the first New Zealand symphonic work and championed a distinctively “New Zealand” musical expression.

Douglas Lilburn died in 2001 as this

country's acknowledged grandfather of classical music. But he made such

a dramatic change of musical direction in the last decades of his

life that fellow composer and Lilburn student Ross Harris -- who

followed in his wake down the electro-acoustic path -- would write,

“In the early 1960s few imagined that [Lilburn] would renounce the

musical idioms which he had already mastered and dedicate the final

years of his composing life to this strange new world".

Douglas Lilburn died in 2001 as this

country's acknowledged grandfather of classical music. But he made such

a dramatic change of musical direction in the last decades of his

life that fellow composer and Lilburn student Ross Harris -- who

followed in his wake down the electro-acoustic path -- would write,

“In the early 1960s few imagined that [Lilburn] would renounce the

musical idioms which he had already mastered and dedicate the final

years of his composing life to this strange new world".

However Lilburn had frequently sought to realise the sound of the New Zealand landscape in his compositions. The possibilities of electronic music – which allowed him to replicate bird sound, waves, wind, rivers and rain, and incorporate taped sounds from the natural world – was a revelation.

Douglas Gordon Lilburn – born at Whanganui in 1915, the seventh child in the family – is being inducted this year into the Australasian Performing Rights Association (APRA) New Zealand Music Hall of Fame, which is not only fitting but belated, given Lilburn was a prime mover behind that organisation which protects artists' rights.

More than a composer, Lilburn was an influential teacher, an advocate for composers to hold copyright on their work, and a generous benefactor.

Not bad for a kid from Drysdale Station near Pukeroa (population about 50 when he was born) who described his schoolboy self as “a myopic bookworm with a passion for music” and didn't finish his music degree. The first he held was an honorary doctorate given to him by the University of Otago in 69. By that time he'd shaped the way at least two generations of classical musicians thought about their place in New Zealand's cultural climate.

Lilburn had initially studied journalism in Christchurch – then considered a respectable profession – but quickly realised it was not for him. He shifted to music. At primary school he'd had rudimentary piano lessons and sang in the choir, at boarding school near Oamaru in “the vast and beautiful South Island” was pianist in the school orchestra and played the handsome pipe organ.

It was at Canterbury University College where he began to hesitantly blossom in the intellectual crucible which also held poets like Denis Glover, D'Arcy Cresswell and Allen Curnow. Ideas about what it meant to be of this country were being debated.

Before completing his degree he entered the 1936 Percy Grainger competition for a new New Zealand composition and won it with his orchestral tone-poem Forest. A remarkable feat given he'd never even heard a live orchestra and had only just turned 20.

His prize money went towards a passage

to England to study at the Royal College of Music (notably with Ralph

Vaughan Williams) and while there composed his Drysdale Overture,

Festival Overture and the choral work Prodigal Country.

The former two won, respectively, first and second place in the

National Centennial Celebrations Competitions in New Zealand, the

latter top award in the choral section.

His prize money went towards a passage

to England to study at the Royal College of Music (notably with Ralph

Vaughan Williams) and while there composed his Drysdale Overture,

Festival Overture and the choral work Prodigal Country.

The former two won, respectively, first and second place in the

National Centennial Celebrations Competitions in New Zealand, the

latter top award in the choral section.

He also composed Overture: Aotearoa for the London commemoration of the centenary of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi.

Lilburn may have been in London, but his head and heart were at home. And – with clouds of war rolling in – he returned to New Zealand.

His works were performed (not always to critical acclaim) but in a nation at war there was no place for a composer so he worked on his sister's farm near Taihape until offered a short term contract conducting the National Broadcasting Service String Orchestra.

He reconnected with friends and fellow-minds like Allen Curnow (for whose poem Landfall in Unknown Seas he provided a complimentary score), the artist Leo Bensemann and – although increasingly aware of his homosexuality – he had a relationship with Rita Angus.

Most notably he was invited to speak at the inaugural Cambridge Summer School in January 1946.

His talk A Search for Tradition is a landmark in New Zealand's cultural life as he argued for a unique musical expression: “I want to plead with you the necessity of having a music of our own, a living tradition of music created in this country, a music that will satisfy those parts of our being that cannot be satisfied by the music of other nations.”

That became his musical drive, even when later in he abandoned composing for instruments and engaged with boxes of wires and knobs.

Douglas Lilburn has been a long time gone. In fact after he retired from teaching in 79 he largely withdrew from public life, pottered around in “the jungle” which grew up protectively around his Wellington home, watched his much-loved Coronation Street, drank cheap cask wine to excess and by most account became increasingly irritable.

As Philip Norman observed in his 2006

biography Douglas Lilburn; His Life and Music, here was a man

who spent much of his life isolated; an artist in a land with no

artistic tradition, a male working in what was perceived as

predominantly a female art, a composer in a country which believed

worthy music could only come from overseas, a homosexual in a

heterosexual world . . .

As Philip Norman observed in his 2006

biography Douglas Lilburn; His Life and Music, here was a man

who spent much of his life isolated; an artist in a land with no

artistic tradition, a male working in what was perceived as

predominantly a female art, a composer in a country which believed

worthy music could only come from overseas, a homosexual in a

heterosexual world . . .

Those electronic compositions of his later life are rarely broadcast and cannot be performed, his classical work is occasionally played but for many it sounds dated. Just echoes of a distant era perhaps.

On his death however there were acknowledgements of his legacy not just in establishing a musical tradition of New Zealand composers responding to this country, but also in the politics of music (publishing, printing of scores, royalties to composers etc) and the generosity of the Lilburn Trust he established.

The musical voice of the much lauded Douglas Lilburn ONZ might now be quieter, but he still speaks to us across the decades because this self-described “musician with the farmer's hands” articulated ideas about New Zealand culture which remain relevant.

In that Search for Tradition

talk almost 70 years ago what he said resonates even now: “We live

in an international age and no one would want us to shut our doors to

it, but I think there is that other danger that if we just sit back

and soak it up, like so many culture-minded sponges, we are likely to

lose our own identity, to become a haphazard creation of the BBC or

Moscow or Hollywood, or any other of the new missionary influences at

work in the world, and our own proper cultural life will remain an

insignificant and unsatisfactory thing.”

In that Search for Tradition

talk almost 70 years ago what he said resonates even now: “We live

in an international age and no one would want us to shut our doors to

it, but I think there is that other danger that if we just sit back

and soak it up, like so many culture-minded sponges, we are likely to

lose our own identity, to become a haphazard creation of the BBC or

Moscow or Hollywood, or any other of the new missionary influences at

work in the world, and our own proper cultural life will remain an

insignificant and unsatisfactory thing.”

Douglas Lilburn, Memories of Early Years and Other Writing edited by Robert Hoskins has just been published by Steele Roberts.

For more on Douglas Lilburn see douglaslilburn.org and sounz.org.nz

His electronic music has been discussed at Elsewhere previously, see here.

post a comment