Graham Reid | | 4 min read

In the early Sixties just before the Beatles conquered America through a combination of art, smarts and image – and shifted the coordinates of popular culture to Britain – America was the nexus of global pop culture and political life.

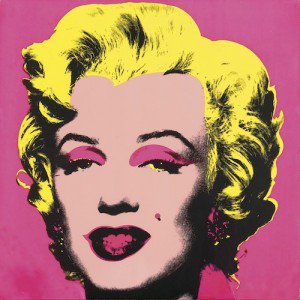

The Kennedys, Hollywood, consumerism, girl groups, John Wayne, Marilyn Monroe . . . . The world had been electrified by Elvis and rock'n'roll in the Fifties, and Disney-fied in Technicolor and Cinerama. In these volatile times of Mao in China and Castro in Cuba and the bitter chill of the Cold War, New York was the new Paris, and California the automobile-dependent dream state of optimism and hard edges under the bright sun.

Is it any wonder that American artists – and those who had grown up with this globalised American iconography – were drawn to these images and the emergent Pop Art movement – which has begun in the mid Fifties – suddenly became the dominant art trend.

A reading of the expansive Pop To Popism at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney (which runs until March 1) confirms the global impact of Pop Art in over 200 works, mostly by big ticket Americans but significant space given over to European and Australian artists. It provide an insight into how artists like Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and Robert Rauschenberg reduced, refined and codified American imagery.

These many artists recalibrated sometimes low culture into high art: “Marilyn Monroe's in everything,” said an exasperated school student during my recent visit.

Not quite true. But Marilyn, Jackie and Elvis (in Warhols), as well as John Wayne (in Marisol's famous sculpture) and Disney figures are as prominent images as pictures collaged from pulp sci-fi and movie magazines (in Scottish-born artist Eduardo Paolozzi's work from the late 50s) and consumer goods like Warhol's 10 screenprints of Campbell's soup cans and Heinz Tomato Ketchup boxes.

In the deconstruction and reconstituting of American imagery, all these disparate elements co-exist within the same space, drawn into a movement by the critical, ironic or satirical comment which the artists bring to bear.

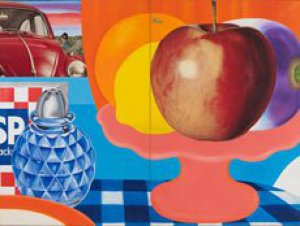

Tom Wesselmann's massive collage and

oil Still Life #29 from 1963 (a key year given the sheer

number of works so dated) is a bright collision of consumer-driven

modernity (a VW Beetle in one corner) and the traditional (the

enormous still life of fruit which occupies two thirds of the

canvas). It stands as an emblem of how Pop Art also ushered in

post-modernism in its appropriating of images.

Tom Wesselmann's massive collage and

oil Still Life #29 from 1963 (a key year given the sheer

number of works so dated) is a bright collision of consumer-driven

modernity (a VW Beetle in one corner) and the traditional (the

enormous still life of fruit which occupies two thirds of the

canvas). It stands as an emblem of how Pop Art also ushered in

post-modernism in its appropriating of images.

Numerous big names are represented in this enormous exhibition – Richard Hamilton, David Hockney, Cindy Sherman, James Rosenquist, Jasper Johns, Gilbert and George, Patrick Caulfield and Robert Indiana among them – but some of the less familiar artists and works are perhaps more of a revelation.

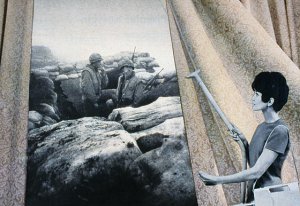

Martha Rosler's photomontages from '67-72 use images from the Vietnam frontlines taken from the pages of Life and slips them them into domestic settings.

The war is now just outside the suburban

window or inside the tidy room as a distraught Vietnamese woman

carried a dead baby up the stairs.

The war is now just outside the suburban

window or inside the tidy room as a distraught Vietnamese woman

carried a dead baby up the stairs.

These are powerful images, perhaps more so today as the bloody brutalities of war are edited out or come with “viewers are warned some images may be disturbing”.

So not everything in Pop To Popism elicits a smile for using pages from Popular Mechanics, photos of Charles Atlas and multiples of consumer goods or Jackie's face.

There is cutting social critique here too as in Warhol's insipidly green and uneasy screenprint of an electric chair (from '67), Hockney's disturbing bleak figures in The Second Marriage ('63) and the Australian Brett Whitely's The American Dream ('68-69) which is a room-filling series of panels he created in New York at the height of the Vietnam war and from the depths of drink and drugs.

The whole exhibition is divided into interesting but interconnected subsets: The Future is Now; Swinging London; The American Dream; Euro Pop, Made in Oz, Late Pop and Popism (the latter looking at work from the 80s and including Jean-Michel Basquiat, the Australian Howard Arkley, Keith Haring and others).

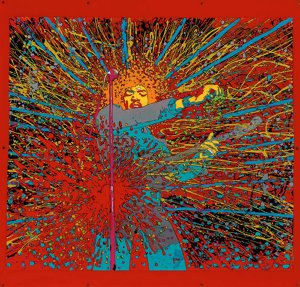

The Made in Oz gallery is immediately striking for the vivid colours deployed by many artists (that hard Australian light?), the proto-feminist and sexually-charged work of Vivienne Binns from 67 (Vag Dens is a vagina with incisors) and a series of intricate screenprints on silver and gold foil (Bob Dylan in Mr Tambourine Man) by the late Martin Sharp, perhaps best known for the album covers he did for Cream in this period, Disraeli Gears and Wheels of Fire.

His large

multi-colour splattered enamel image of Jimi Hendrix ('71) is

wonderfully energetic and suitably psychedelic.

His large

multi-colour splattered enamel image of Jimi Hendrix ('71) is

wonderfully energetic and suitably psychedelic.

There is also the rage of Mike Brown's Hallelujah! collage (65) which is littered with provocative obscenities and the very Australian “bloody stuffit upya”. The provocation worked and he was sentences to three months hard labour for obscenity (although this was reduced on appeal to a $20 fine although the conviction was upheld).

At the time of writing no one it seems has complained about his Big Mess next to it from the same period which has “Fuck the bloody Pope” quite prominent.

Times change as do our sensitivities, although in Icelandic artist Erro's Pop History (67) – which cleverly appropriates images from Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Rosenquist and others – his caricatures of Russians as crazed Cossacks do come perilously close to how Nazi propaganda portrayed Jews. But in much brighter colours, of course.

And New Zealand-born Colin Lanceley and Ross Crothall are here too, part of the short-lived Annandale Imitation Realist Group with Brown.

Pop Art – the movement which repositioned the commonplace, the ordinary and popular culture into the forefront of American and then international art – changed our world and still challenges us, especially a Chinese tour group which stood bewildered by Warhol's soup can screenprints.

Without Pop Art we probably wouldn't see graphic novels essayed in the New York Review of Books, Arnold Schwarzenegger might never have been governor of California, there would be no Obama “Hope” posters by Shepard Fairey.

There probably wouldn't have been New Journalism, no columnists writing about their own lives rather than the workings of political or economic elite and none of those Lichtenstein-style cartoon ads on Auckland's buses.

As an exhibition Pop To Popism – which run from the amusing and entertaining to the provocative and gripping -- makes you think, “Whaam!”

Pop To Popism, Art Gallery NSW until March 1

Graham Reid traveled to Sydney with assistance from Destination NSW.

For more information visit www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au or www.sydney.com

post a comment