Graham Reid | | 2 min read

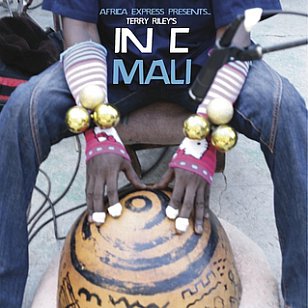

Many years ago someone told me a Chinese ensemble did a treatmernt of Terry Riley's cornerstone minimalist piece In C, "But the buggers didn't play it in C," he laughed.

I have no idea whether that is true or not, but it's a good joke anyway.

In C -- first performed in November '64 -- is widely considered to be, if not the first, then certainly the first widely significant minimalist composition.

Earlier work along not dissimilar lines by the great La Monte Young (profiled here) were certainly influential among musicians, but Riley's piece captured the imagination of the wider populace.

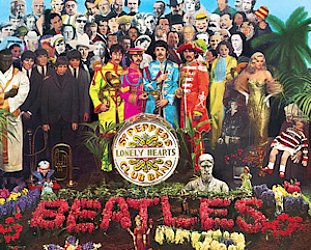

Thereafter, it was all on for minimalism and although composers such as Philip Glass and Steve Reich, and Glenn Branca with his guitar orchestras to a lesser extent -- who composed pieces of equally narrow structure and repetition -- would come to reject the label, as a taxonomic device to speak about a style, "minimalism" was as useful a term as any.

Riley's In C was unique in Western classical music for a number of reasons, not only was it constructed of short patterns (53) but they could be repeated in an arbitrary way so the piece could morph and flex into subtle shapes, and therefore also be of an indeterminate length.

Riley also didn't notate it in such a way as there should be a set number of performers, so the piece also became an interesting challenge and proving ground for any number of ensembles.

It has lent itself to beng played by percussion ensembles, guitar groups, string players and . . .

And now a group of musicians from Mali who -- with Brian Eno, Damon Albarn (on his favoured melodica) and guitarists Nick Zinner and Jeff Wootton -- recorded it in Bamako under the direction of conductor Andre De Ridder.

Given that there are numerous West African styles which have repetition as a key component, this treatment sounds faithful but exotically right -- especially when the koras become prominent at around the 15 minute mark of the 40 minute piece, then scraping violin enters.

The solid bottom is held down by calabash, balafon, kalimba (thumb piano) and other tuned percussion, and the whole piece has a hypnotic but constantly changing feel. And then around the midpoint there is a dramatic shift when -- after everything dissipates into almost nothingness with just guitar and kora, and a quiet spoken word section with a distant singer -- the piece soars again with renewed urgency and energy.

In C is by its very nature a malleable work, but the liberties here taken with it means the performers have placed their own, distinctively African stamp on it.

It really is quite something.

It really is quite something.

And what did Terry Riley -- who turns 80 this June -- make of it?

"I was not prepared for such an incredible journey, hearing the soul of Africa in joyous flight over those 53 patterns of In C.

"This enemble feeds the piece with ancient threads of musical wisdom and humanity, indicating to me that this work is a vessel ready to receive and be shaped by the spontaneous feelings and colours of the magician/musician.

"I could not ask for a greater gift for this daughter's 50th birthday."

This version of In C is available in New Zealand on Transgressive through Southbound. Because this is one long piece Elsewhere cannot upload just one section, however it is featured in the documentary clip below.

This version of In C is available in New Zealand on Transgressive through Southbound. Because this is one long piece Elsewhere cannot upload just one section, however it is featured in the documentary clip below.

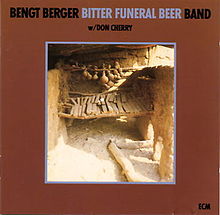

If this kind of music with an African twist is of interest, then try to locate a copy of the ECM album Bitter Funeral Beer by Bengt Berger and a large ensemble, released in 1981.

There is a live album of this (mostly) Swedish ensemble with trumpeter Don Cherry available for free streaming here.

post a comment