Graham Reid | | 5 min read

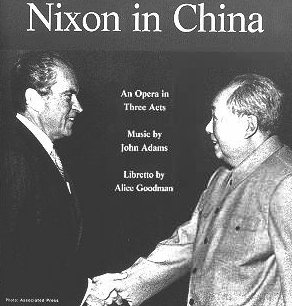

Although it is his autobiography and he's allowed to exclude whomever and whatever he wants, it did seem odd that Philip Glass would not have mentioned John Adams' opera Nixon in China in his recent book Words Without Music.

Both Glass and Adams – along with Steve Reich – redefined the parameters of opera in the late 20th century with their enormous multi-media works. And all three had at least some of their musical roots in the minimalist style.

Of course there is considerably more which separates these composers than connects them and of the three Adams stands apart even further.

Unlike New York-based Glass and Reich, Adams from smalltown and rural New England – after graduating from Harvard – mostly made his name on the West Coast as a teacher and composer.

His early work and even his more recent compositions often explore the poetry and mythology of the American landscape, and perhaps that explains why Adams is the most widely performed of America's living composers.

And that's despite the fact he mounts massive operas like Nixon in China and The Death of Klinghoffer, both rooted in contemporary events and fueled by divisive politics.

But Adams is also a child of his

generation: He grew up in the Sixties, played in school marching band

and loved big-band swing (as a kid he sat next to Ellington at the

piano when the master's band played at the local hall) and was at

heart a populist, even when listening to often impenetrable music of

demanding mid-20th century classical composers at Harvard.

But Adams is also a child of his

generation: He grew up in the Sixties, played in school marching band

and loved big-band swing (as a kid he sat next to Ellington at the

piano when the master's band played at the local hall) and was at

heart a populist, even when listening to often impenetrable music of

demanding mid-20th century classical composers at Harvard.

He loved the Beatles and has spoken about being suspicious of “inspiration”. If you work at the composing job every day, he says, ideas tend to arrive when they are needed because you have flexed those muscles.

He describes himself as a “a blue collar worker when it comes to being a composer”.

Sort of Springsteen with a string section? Hmm, not really.

But he does distance himself from the elitist classical music which he felt dominated much of the discussion in music academies.

In Hail Bop!, Tony Palmer's 2009 film portrait of him, Adams spoke bluntly about the classical music which marginalises audiences.

“By composing the kind of self-referential, complex, difficult music that has evolved during the latter part of the 20th century, these composers have abnegated their place in the culture, that the music they compose does not have the cultural influence that the music of the great composers of the 19th century and the 18th century had.

“I remember reading Milton Babbitt's

famous article Who Cares If You Listen? [in 1958] and finding there

was a cavalier indifference on the part of a lot of contemporary

composers, that they knew they had no audience and had created a

mindset, an attitude, which basically said, 'Screw you'.

“I remember reading Milton Babbitt's

famous article Who Cares If You Listen? [in 1958] and finding there

was a cavalier indifference on the part of a lot of contemporary

composers, that they knew they had no audience and had created a

mindset, an attitude, which basically said, 'Screw you'.

“I remember Babbitt [pictured] saying he would no sooner expect the average listener to understand his music than he would this person to understand a paper by a nuclear scientist.

“That struck me as a very arrogant attitude.”

Adams also noted that this difficult music was circulated and accessible to people, but despite performances it had not made an impact on the culture because of its inaccessibility. He laughingly said that his own music was often described by critics as “accessible” and this was levelled at him “as a devastating criticism”.

He joked — and this is wearily familiar to anyone who reads music or art criticism — that for many critics and writers, if art is approachable or accessible then there's something wrong with it.

But we live in different times and have so many ideas available to us that audiences can move into difficult areas, but there are some they shun, perhaps for good reason. It is not a reflection on the audiences intellect.

Where Phillip Glass has spoken about crossover audiences not crossover music, Adams talks of “post-stylism” which is “a very healthy thing”.

His work embraces electric guitars and jazz ensembles as much as it does the classical orchestra or strings.

As Alex Ross noted in The Rest is

Noise, “Minimalism gave Adams his individual voice. His defining

move was to combine Reich-Glass repetition with the sprawling forms

and grandiose orchestration of Wagner, Mahler and Sibelius.”

As Alex Ross noted in The Rest is

Noise, “Minimalism gave Adams his individual voice. His defining

move was to combine Reich-Glass repetition with the sprawling forms

and grandiose orchestration of Wagner, Mahler and Sibelius.”

It is that drama coupled with material and ideas which matter to his broad audience which has set Adams apart.

No more so than with his three-act opera Nixon in China (first performed in Houston in October '87 to very mixed reviews) and which is still being mounted today. A truncated, “semi-staged” version will be performed in Auckland's Arts Festival in March 2016 (see details below).

It is a big affair but Adams joked that he was considered a “minimalist so people expect you to take 30 minutes to get off the runway. And I write opera, an even more sluggish species”.

On the face of it, Nixon in China is an

odd one: “Nothing seems more inherently unlikely,” wrote Ross in

The Rest is Noise, “than the idea of a great American opera —

possibly the greatest since Porgy and Bess – based on events

surrounding President Richard Nixon's visit to China in 1972”.

On the face of it, Nixon in China is an

odd one: “Nothing seems more inherently unlikely,” wrote Ross in

The Rest is Noise, “than the idea of a great American opera —

possibly the greatest since Porgy and Bess – based on events

surrounding President Richard Nixon's visit to China in 1972”.

But the fact it was American and not European is a large measure of its success, that was why it connected with American – and then global — audiences. There was a historic cultural and political clash at that time played out by flawed characters which makes for great drama.

The libretto by poet Alice Goodman pulled lines straight from the documentary record of the time: the speeches of Chairman Mao and Chinese PM Zhou En Lai, and passages from Nixon's memoirs.

It also acknowledged the electronic age (“It's prime time in the USA,” sings Nixon, “It's yesterday night. They watch us now, the three major networks' colours glow . . . .”

But this is also the Nixon we know and hate: the secretive man, paranoid and vindictive, a man believing he is surrounded by enemies: “The rats begin to chew . . . now there's ingratitude”

One of the themes is that of cultural

control (American and Chinese both), there are elements of kitsch

(the mocked Chinese revolutionary opera which however seems so real

to Mrs Nixon) and the consumerism of American capitalism.

One of the themes is that of cultural

control (American and Chinese both), there are elements of kitsch

(the mocked Chinese revolutionary opera which however seems so real

to Mrs Nixon) and the consumerism of American capitalism.

Adams explains it this way: “It is the collision of the two great myths of my childhood, capitalism and this sense that the marketplace is the principle dictating factor of one's life, this is the way we live in the United States.

“This is McDonalds, this is Disney, this is Coca-Cola, this is Richard Nixon and all the Protestant rectitude that comes along with it. And this whole mass was coming face-to-face in this one moment in Peking with Communism, Chairman Mao and for what Americans was the big, dark evil monster.

“That's the kind of mindset that dominated my childhood, so the story of Nixon in China was at one moment banal and funny and ludicrous, the way that politicians are. And on the other hand it had a kind of titanic, Wagnerian mythological weight to it because of this collision of cultures.”

That banal, funny and ludicrous aspect is heightened by moments of absurdity . . . all too real because this was history as theatre.

Humour is something all too rare in the higher arts, but as Shakespeare's tragedies showed, serious drama becomes all the more so by the occasional presence of a fool, a drunkard or . . . a dancing president?

NIXON IN CHINA

Auckland Arts Festival in association with Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra and New Zealand Opera

Conductor – Joseph Mechavich

Hye Jung Lee – Madame Mao

Madeleine Pierard – Patricia Nixon

Simon O’Neill – Mao Zedong

Barry Ryan – Richard Nixon

Chen Ye Yuan – Zhou En Lai

17 March and 19 March 2016

Great Hall, Auckland Town Hall

post a comment