Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Te Aho Ku, by Hirini Melbourne, Richard Nunns, Aroha Yates-Smith

On Waiheke, one of the islands in the Waitemata Harbour of Auckland, there is a remarkable private museum of musical instruments.

It is exceptional in one key detail.

As many would know, museums lovingly curate their instruments in glass cases and protect them closely. Sometimes too closely.

At a museum in Rome I was once followed by a small and seemingly angry guard who would jump behind the nearest case when she suspected I knew she was tailing me. She was sure in her expectation I would smash a glass and be off down the two flights of stairs with a massive 18thcentury sitar.

At a similarly well-stocked museum in Brussels I stood too long in admiration of some instruments and was asked by a museum person if I needed any help.

I was being encouraged to move along.

At the Auckland War Memorial Museum the instruments are similarly housed . . . and mute.

It is lovely to admire the design and craftsmanship which has gone into many historic or exotic instruments, but they only make any sense when you can hear what they sound like.

And that is why Whittaker's Music Museum on Waiheke is so different.

The instruments are right there (few behind glass) and they are played regularly on weekends by the owners or guest musicians.

It is worth a visit to the island – it's a boat trip and short bus ride to their site behind the library – just to hear the sounds of their historic collection.

It's hard to believe – given how often we hear traditional Maori instruments (taonga puoro) played these days in concert and on recordings – that not too long ago most people (Maori among them) had not heard the evocative sound of the various traditional instruments.

It was little more than 30 years back in fact, that a small group began to wonder aloud what those carved objects they'd seen in books or behind the glass sounded like.

In the vanguard of that enquiry and to bring the sounds out of the silent darkness, teacher and musician Richard Nunns, master carver and instrument maker Brian Flintoff (both Pakeha) and Maori composer, musician and educator Hirini Melbourne (who died in 2003) began a journey which inspired discussion, experimentation, recovering memories from many older Maori . . .

In the vanguard of that enquiry and to bring the sounds out of the silent darkness, teacher and musician Richard Nunns, master carver and instrument maker Brian Flintoff (both Pakeha) and Maori composer, musician and educator Hirini Melbourne (who died in 2003) began a journey which inspired discussion, experimentation, recovering memories from many older Maori . . .

And consequently led to the renaissance of taonga puoro.

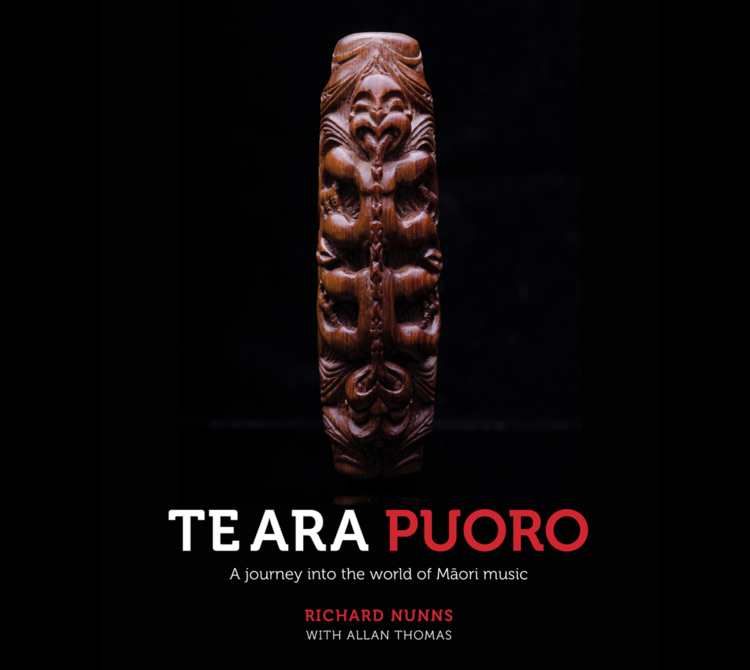

In the marvellous book Te Ara Puoro; A Journey into the World of Maori Music, Richard Nunns tells – in an easy conversational manner – of how he was teaching in the Waikato which lead to his involvement with the Maori students and parents. And how he discovered another country beyond that which he had grown up with as the son of Pakeha with roots in Germany and England.

In the marvellous book Te Ara Puoro; A Journey into the World of Maori Music, Richard Nunns tells – in an easy conversational manner – of how he was teaching in the Waikato which lead to his involvement with the Maori students and parents. And how he discovered another country beyond that which he had grown up with as the son of Pakeha with roots in Germany and England.

Here was not just a different way of life but of thinking and culture, and when he came on an article about Maori instruments in the Auckland Weekly News (“I still have the article. It serves well as a starting point of my journey of discovery”) he wondered how they had been played, and what they sounded like.

As he writes in the handsomely presented coffeetable-cum-reference hardback with numerous colour photographs of the instruments, this also made him wonder what the role of these instruments was in Maori society and why they had disappeared.

An important hui in 1984 at Hinerupe marae on the East Coast was the nexus of Nunns, Flintoff and Melbourne's lifetime of engagement with Maori instruments.

The former two were tutors and Melbourne was a student and respected musician, but had not -- as few had -- played taonga puoro.

Flintoff brought mutton-bone shanks and wooden blanks to make into instruments, and Bill Cooper from the National Museum turned up a large number of the real thing from the museum's collection.

Flintoff brought mutton-bone shanks and wooden blanks to make into instruments, and Bill Cooper from the National Museum turned up a large number of the real thing from the museum's collection.

The treasures were out of the case and into the hands of the people. And from then on there could no putting them back or consigning them to silence.

And so the story unfolds through experimentation in playing techniques, making instruments, asking Maori elders what they remembered of the sounds, some natural suspicion that two Pakeha were entering this world . . .

There had been a few recordings of traditional instruments (the book shows the cover of a Viking album Traditional Music of the Maori by Mrs Paeroa Wineera released in the late Sixties) but mostly it was try, ask, try again, talk . . . a research based on dialogue.

There had been a few recordings of traditional instruments (the book shows the cover of a Viking album Traditional Music of the Maori by Mrs Paeroa Wineera released in the late Sixties) but mostly it was try, ask, try again, talk . . . a research based on dialogue.

Nunns quotes his co-writer and respected ethnomusicologist Allan Thomas (1942-2010) of Victoria University as writing, “This is one of most profound 'decolonisations' of Ethnomusicology which has occurred. It has shown to be enormously productive in contributing to the rebirth of a tradition”.

Much of this exploration was done by working in the absence of information but intelligent speculation: Simple but important questions like, when Maori had arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand some 800 years previous what was that land like?

Deafening probably: myriad birds with various calls, huge swathes of bush battered by gales and rain, the surge of the ocean hammering on the sand, boulders and cliffs, the howl of wind through rocks and trees . . .

Perhaps the instruments – many of them version of short flutes (koauau), the purerehua whirled above the head creating a roaring sound – evoked all of these, as well as laments and yearning, tunes to soothe and heal, music to communicate in secret . . .

In beautifully illustrated pages with photos and descriptions of the many instruments, Nunns and co-author Thomas take the reader on this extraordinary journey of music and culture.

And it comes right up to how these instruments are now heard in new contexts: Nunns performing with British jazz saxophonist Evan Parker in 2000 and recording with jazz pianist Judy Bailey in 2004, taonga puoro used in films such as Once Were Warriors in '94 (Mereta Mita's '88 Mauri one of the first features to include them) and more.

There have been dozens of recordings from classical to jazz to albums by Moana and the Tribe, Little Bushman and Lizzie Marvelly where the distinctive sound of the instruments can be heard.

There have been dozens of recordings from classical to jazz to albums by Moana and the Tribe, Little Bushman and Lizzie Marvelly where the distinctive sound of the instruments can be heard.

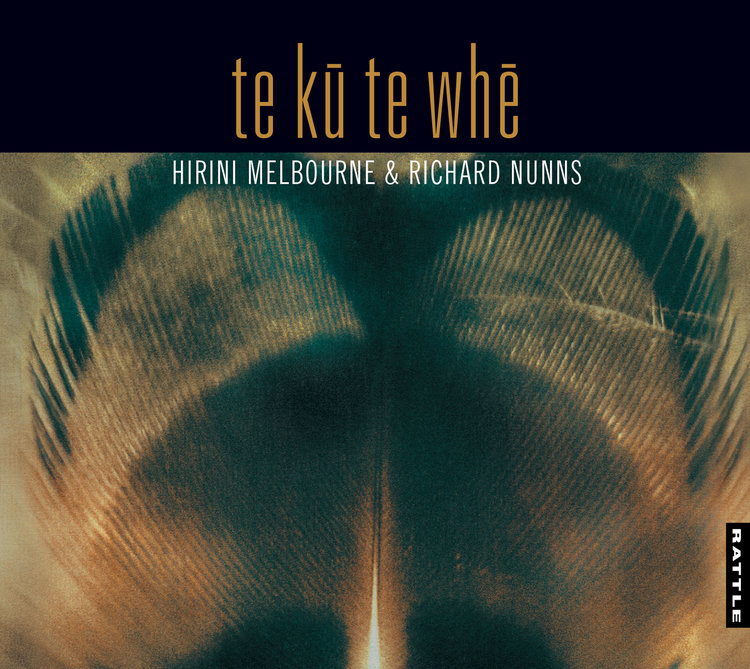

But few were more significant than the Melbourne/Nunns album Te Ku Te Whe on Rattle in '94.

Douglas Lilburn said he'd been waiting all his life to hear such sounds and the album – against Rattle's expectations – became one of the best sellers in its catalogue. It prompted a follow-up album two years later with the original sounds remixed by the likes of Chris Macro, SJD, Rhian Sheehan, Pitch Black, Sola Rosa, Victoria Kelly and others.

Rattle's catalogue now contains numerous examples of albums using taonga puoro, most recently by Al Fraser, Rob Thorne and others who represents a new generation of sonic explorers using these taonga.

Rattle's catalogue now contains numerous examples of albums using taonga puoro, most recently by Al Fraser, Rob Thorne and others who represents a new generation of sonic explorers using these taonga.

The Nunns book comes with a sampler CD of 16 tracks from the Rattle catalogue by artists as diverse as Gillian Whitehead, John Psathas, Marilyn Crispell, Dave Lisik, Pitch Black and of course the late Hirini Melbourne and Richard Nunns.

Hard to believe that a little over three decades ago these evocative sounds, now such an integral part of our musical and physical landscape, were rarely -- if ever -- heard.

Here is the story of how they were rescued from the darkness.

Here is the story of how they were rescued from the darkness.

Te Ara Puoro; A Journey into the World of Maori Music by Richard Nunns with Allan Thomas is a large format hardback published by Craig Potton Publishing (with the Rattle sampler CD) is available through Rattle's bandcamp page here (minimum price just NZ$25).

Elsewhere has an archived interview with Richard Nunns here.

For more on Whittaker's Music Museum on Waiheke see here

post a comment