Graham Reid | | 3 min read

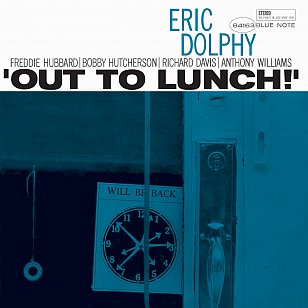

Eric Dolphy: Something Sweet, Something Tender

The sudden and unexpected death of saxophonist/flute player and clarinettist Eric Dolphy just months after these exceptional studio sessions for the Blue Note label robbed jazz of one of its most distinctive voices, and left many questions hanging about where the 36-year old might have taken his music.

Already he had worked with Charles Mingus, Max Roach, George Russell and John Coltrane -- and that had only been in a six year period on arriving in the New York scene after time in groups on the West Coast and playing sessions (Sammy Davis Jnr).

Dolphy’s first album under his own name -- Outward Bound, which included trumpeter Freddie Hubbard in the line-up -- had been a mere four years before his death and yet it was clear here was someone prepared to pick up the challenge of the era.

As one writer put it, “if [Outward Bound] lacks the sudden, alienating wallop of an equivalent dose of Ornette Coleman or Cecil Taylor, it’s no less challenging”.

And it got him work: he played on almost two dozen other albums within the next year, was signed to Blue Note (from his first sessions for the label the somewhat disappointing Other Aspects, a collection of odds and sods, wasn’t released until the Eighties), and saw him playing in Europe with Mingus again after being a member of Coltrane’s group in ‘62.

There are a lot of albums with Dolphy’s name on them but Out to Lunch is different. Richard Cook and Brian Morton in their Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD say it is “one of a handful of absolutely essential post-war jazz records [and] although Dolphy had played better, he never had a more cohesive or responsive band”.

And Out to Lunch is undeniably a band album with Hubbard, vibes player Bobby Hutcherson, bassist Richard Davis and drummer Tony Williams entirely in sympathy with Dolphy’s playing which is referenced in Charlie Parker’s flittering style as much as Ornette Coleman’s stabbing and repeated-figures (Dolphy played on Coleman‘s ground-breaking Free Jazz album of 1960), and Cecil Taylor’s challenging and brusque atonality.

As with Coltrane, Dolphy had listened to the music of Ravi Shankar for inspiration: his playing on Coltrane’s India album shows how quickly he had assimilated some raga elements. And yet he also possessed a fat and hard tone on bass clarinet, and Out to Lunch showcases his exceptional flute playing.

But what this album possesses more than anything else is a confidence and completeness: it is Dolphy as jazz revolutionary who knows the texts from the past but is hearing the space in which he can take the music. The other players were no mere ring-ins for these Blue Note sessions but had worked with Dolphy previously and were conversant with the breadth of his many styles.

There is free playing here from Williams who pushes and prods, and in that it signalled where Dolphy -- always holding melody and composition dear to his heart -- might have gone.

But then he was quite literally gone, dead of a heart attack in Germany before Out To Lunch was released, and the liner notes didn’t mention that he had passed on.

Listened to Out to Lunch now, it is as commanding and demanding as it was over four decades ago, which says something about how so many young -- and older -- jazz musicians have retreated from the barricades, and the frontiers that Dolphy saw should be explored as part of the essential contract of jazz.

Out to Lunch has been re-presented on 180gm vinyl (with a download code for an mp3 version) as part of an on-going vinyl reissue programme to celebrate Blue Note's 75th anniversary.

Everything about Out to Lunch -- from the classic Reid Miles cover photo and design to Rudi Van Gelder’s focused production -- is so close to jazz perfection as a human statement that it would be churlish to argue with it.

And anyway, playing this exceptional album closes down debate -- but does leave that sad speculation about what Eric Dolphy might have achieved given more time.

And anyway, playing this exceptional album closes down debate -- but does leave that sad speculation about what Eric Dolphy might have achieved given more time.

We’ll never know.

But what an aural epitaph he left.

For more on Blue Note, the artists old and new on the label, the artwork on its covers and the reissue programme, start your reading and listening here.

These Essential Elsewhere pages deliberately point to albums which you might not have thought of, or have even heard . . .

But they might just open a door into a new kind of music, or an artist you didn't know of.

Or someone you may have thought was just plain boring.

But here is the way into a new/interesting/different music . . .

Jump in.

The deep end won't be out of your depth . . .

post a comment