Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Charles Mingus: Goodbye Pork Pie Hat (1959)

Like Duke Ellington -- with whom he is most frequently (and fairly) compared for the vastness, depth and diversity of his recordings -- no single album could stand as emblematic of Charles Mingus, although many are certainly essential.

In fact after The Wire magazine offered its primer on Mingus albums in early 2004 (14 albums under his own name, a Columbia Records compilation and a few with the likes of Charlie Parker and Duke Ellington) there were letters arguing for the inclusion of others.

That was Charles Mingus: too big, too broad, too deep . . . just too much to be readily distilled.

Today, 30 years on from his death, more -- and just as complex Mingus and Mingus-affected -- music is being released. The posthumous releases began with Joni Mitchell’s Mingus album which came shortly after his death. She had spent the final months of his life with him and set lyrics to some of his melodies.

Then there was Weird Nightmare, the 1992 tribute to Mingus pulled together by producer and conceptualist Hal Willner which included guests Keith Richards, Elvis Costello, Leonard Cohen, Bill Frisell and others. Since then there has been the release of bootlegs and unofficial recordings, and his legacy is carried on by the Mingus Dynasty and the Mingus Big Band which his wife Susan encouraged into existence.

There’s a lotta Mingus out there and Mingus -- like Bird -- lives.

This collection on Atlantic and compiled by Rhino -- wholly inadequate but in its own way an excellent introduction -- cannot begin to encapsulate the man’s music but it has the advantage of drawing from some of the multiple labels Mingus recorded for and includes material not often in the frontline when people are talking about him.

And people, not just jazz listeners, do still talk about the awkward, angry and restless spirit that was Charles Mingus.

He

was born in Arizona in 1922 but grew up in Watts, Los Angeles and was of

multiple mixed races (black, white, Chinese). As a result he didn‘t quite fit

anywhere, and nor did his music which drew on numerous sources such as blues,

jazz, Third Stream, soul, gospel, spoken word and nursery rhymes, South

American sounds -- and at times had an almost pop quality. Towards the end of

his life he was working with electric guitarists like John Scofield and

attempting to get to the rock audience which had been drawn to fusion by the

likes of Miles Davis jazz-rock albums, Jeff Beck and John McLaughlin.

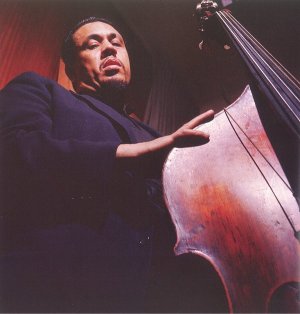

A bassist, pianist and, like Ornette Coleman, he was most commonly referred to as “a composer” because he transcended the smaller categories.

“Mingus’ main contribution was as a composer,” said Dizzy Gillespie on Mingus‘ death in 1979. “Mingus tunes were sort of uniquely . . . Mingus. It’s not like he was out there writing for everybody. He was more personal than that. He was immensely gifted as a writer.”

Before moving to New York in the early Fifties he had, as a bassist, played with Barney Bigard, toured briefly with Louis Armstrong and then for a year with Lionel Hampton, and then with the Red Norvo Trio.

But his natural home was the vibrant musical melting pot of New York in the post-war period where he played with Miles Davis, Parker, Ellington, Bud Powell, Lennie Tristano, Art Tatum and others.

He started his own record label and a band under his own name, and in 1956 released the first of many essential albums Pithecanthropus Erectus, a broadly conceptual album which he said was “a jazz tone poem because it depicts musically my conception of the modern counterpart of the first man to stand erect -- how proud he was“.

Typically though, the arc of the music traces the fall as much as the rise of Man in a series of movements. The title track, included on this double-disc collection was, according to Mingus biographer Brian Morton writing in The Wire, “a new tonal and timbral palette that was like nothing else on the scene”.

Concepts, movements, broad strokes, lengthy compositions, highly composed sections juxtaposed with space for the bebop players of his generation . . . These were all hallmarks of Mingus’ music.

In 1959 -- the same year Davis released his classic Kind of Blue (Mingus had been into modal playing before him) and Coleman delivered his provocative Tomorrow is the Question -- Mingus released the equally important Mingus Ah Um, “an extended tribute to ancestors” according to Richard Cook and Morton’s Encyclopaedia of Jazz. There is gospel and swing and blues in the grooves alongside shouts and yells.

“Charles Mingus was one of those rare human beings who created his own musical language,” said fellow bassist Charlie Haden. ”He dedicated his life to creative thought and expression.”

And he wasn’t averse to giving his pieces odd titles (as Frank Zappa would later do).

Amongst

his body of work are Better Git It in Your Soul, Wham Bam Thank You Ma’am,

All The Things You Could Be By Now If Sigmund Freud’s Wife Was Your Mother, If

Charlie Parker Were A Gunslinger There’d Be A Whole Lot of Dead Copycats, Don’t

Be Afraid, the Clown’s Afraid Too, The Shoes of the Fisherman’s Wife are Some

Jive-Ass Slippers . . .

Such titles often mask the seriousness of his approach and he was merciless and often violently cantankerous band leader. He was as muscular as his music and the number of players he fell out with were legion.

In his book of “imaginative criticism as fiction”, But Beautiful, the writer Geoff Dyer painted a portrait in print of Mingus.

“His rage never left him. Even when he was calm the pilot light of his anger was blinking away, ready to erupt at any moment. Even when he was quiet some part of his head was yelling. He didn’t know why he was the way he was, but he knew he had to be that way and no other. His rage was a form of energy, a fire sweeping through him.”

And later: “ For Mingus there was no such thing as contradiction: the fact that something was done or sad by him lent it an automatic integrity.”

An awkward man to work with, but he never had too much difficulty in finding those willing to immerse themselves in his magisterial music.

As Dyer notes, “his life was an obstacle course”.

But Mingus cleared more hurdles than he fell at. And left behind a legacy of great music, a mere fragment of it in these Thirteen Pictures.

Here is Goodbye Pork Pie Hat from Mingus Ah Um, his beautiful and allegedly spontaneously improvised farewell to Lester Young written after the tenor man’s death and which has become a jazz standard.

Here too is his salute to Thelonious Monk (Jump Monk), a solo piano piece Myself When I am Real (“an improvised solo and which I am very proud of”) and the sprawling, 10 minute Pithecanthropus Erectus.

Here too is Wig Wise with Ellington on piano, Max Roach on drums and Mingus on bass. Taken from the album Money Jungle and produced by Alan Douglas (who controversially curated Hendrix albums after the guitarist's death), it is a rare album in the canon of either Ellington or Mingus.

They weren’t an easy two days recording though: “Charlie got pissed off with Max,” recalled Douglas in the early Seventies. “They had a big fight and ran out of the studio. I always remember this vision of Duke chasing Charlie up 57th Street in an attempt to get him back into the session.”

On that rare album however Ellington sounds fiery and inspired, but it is Mingus’ thrilling, rapid and complex playing (always “in the pocket” as they say) which is outstanding.

There

are at least half a dozen Mingus albums which should be in any serious music

collection. Certainly Pithecanthropus Erectus, Mingus Ah Um, The Black Saint

and the Sinner Lady from ‘63 (where he and producer Teo Macero spliced tapes

together a decade before Macero was doing the same for Miles Davis), Cumbia

and Jazz Fusion from the year years before his death (the funky, 27 minute

South American suite-like title track opens this collection) . . . and perhaps as many more if his many

aficionados had their vote.

But as a starter Thirteen Pictures is useful. It is wide (solo piano to an orchestra on Half-Mast Intuition) and it is deep (Meditations on Integration Parts I and II). It includes some cornerstone Mingus material (those previously mentioned as well as Haitian Fight Song, Better Git It In Your Soul and Ecclusiastics which is “hectically brilliant” according to Morton in the extensive liner essay on each track).

These tracks also have a rollcall of great players (Mal Waldron, John Handy, Eric Dolphy, Lee Konitz, Jackie McLean, Booker Ervin, Jaki Byard, Roland Kirk and more) which stands as testimony of the regard in which Mingus was held by his peers.

They knew they were in the company of genius, wherever it came from.

“What I write and play,” he used to remind critics, record company suits, audiences and club owners, “is Mingus music!”

And there is no other music like it.

These Essential Elsewhere pages deliberately point to albums which you might not have thought of, or have even heard . . .

But they might just open a door into a new kind of music, or an artist you didn't know of. Or someone you may have thought was just plain boring.

But here is the way into a new/interesting/different music . . .

Jump in.

The deep end won't be out of your depth . . .

post a comment