Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Rainy Day Dream Away

There's a very good case to be made that The Jimi Hendrix Experience album of 1967 was the most accomplished and innovative debut of the rock era. (Indeed I hope I made the case for Are You Experienced at Elsewhere with my free-ranging, autobiographical essay Jimi Hendrix: In My Life).

This was an album which changed the boundaries of what was possible on guitar -- and by extension in rock music -- and in it Hendrix wrote the template for all that would follow in his meteoric and short life.

Had he lived he may well have explored the jazz-fusion connection with Miles Davis (he almost did but as Hendrix's friend and late-in-life mentor Alan Douglas says, Davis held out for a ridiculous amount of money at the last minute) or he could have gone the whole free jazz/James Blood Ulmer direction.

The trajectory of Hendrix's recordings offers no easy answer to any direction: after that debut there was the pallid Axis: Bold As Love; then this ambitious double album of studio recordings and jams; and finally the live Band of Gypsys which had him going a kind a funk route. The unfinished albums, hundreds hours of studio sessions or late live recordings leave no clear hint at what was going to come from a man who had already proven the impossible on guitar was right there in his finger-tips. But the pop hits were being quickly relegated to the past.

So in his lifetime just three studio albums, the last of which is Electric Ladyland, an extraordinary if sprawling collection of pop-rock, blues, psychedelic explorations, sonic effects, the prototype for heavy metal and much, much more.

Although that debut had a couple of flat points -- Can You See Me and Remember aren't his most memorable moments -- and this one has accordingly a few more simply by virtue of being so much longer (would anyone miss Noel Redding's Little Miss Strange which sounds grounded in the pre-67 past?), these are the two pivots on which any Hendrix discussion (and collection) rests.

Among the more remarkable aspects of this album -- widely considered one of the finest in rock -- is that it was being recorded at a time when Hendrix was constantly touring. Yet he was meticulous in the studio and recorded multiple takes of every track and every part.

The sessions were also wide open and guests would drop by, among them Jefferson Airplane bassist Jack Cassidy, Dylan offsider Al Kooper on piano and Stevie Winwood on organ who were all credited . . . and Rolling Stone Brian Jones and a taxi driver on congas who aren't. Yet Hendrix (mostly) kept a firm grip on proceedings. He "produced and directed" the album himself and wanted it to be his masterpiece.

Indeed much of it can fairly claim that: notably the integrated third side Rainy Day Dream Away/1983/Moon Turn the Tides Away which is a psychedelic trip of sonic effects and dreamy melodies.

The final side which follows could not be more different: the energy levels and guitars are turned up opening with a funky wah-wah peddle on Still Raining Still Dreaming (a reprise of the piece from the third side) then the incendiary House Burning Down, his seminal cover of Dylan's All Along the Watchtower (the style of which Dylan would adopt for over a decade when he played it) and the final version of Voodoo Chile (Slight Return) which unleashes a monster guitar part that is breathtaking in its breadth and density.

From the opening sonics on side one (tapes slowed down, the dreamy Electric Ladyland leading to the thrilling Crosstown Traffic and the slow bluesy version of Voodoo Chile) to this final, noisy and angry reworking, this was a double album which wasn't so much conceptual as a journey.

Hendrix spent a lot of time getting the running order just right so that it takes the listener through changing moods and is an astral flight through musical styles which includes references to blues (Voodoo Chile), jazz (Rainy Day), gospel (Long Hot Summer Night), Fifties rock'n'roll (Come On), electric funk (Gypsy Eyes) . . .

There are Hendrix's sci-fi space lyrics here, but also references to the current political landscape in that explosive year 1968 with the Watts riots (House Burning Down). And the studio is an instrument in engineer Eddie Kramer's and Hendrix's hands: there are cross fades, layering, phasing, multiple overdubs, variable speeds, odd instruments . . .

Electric Ladyland was a major landmark in rock and the irony of Hendrix's final words on this, his last studio album, ("if I don't see you no more in this world, I'll see you in the next one") are not lost on anyone who listens.

The 40th anniversary edition of the album (remaster by Kramer) came with an expanded version of the 1997 doco about the making of it: here Kramer deconstructs some of the tracks at the mixing desk so you can hear its complexity, commentary comes from Experience members Mitch Mitchell (drums) and a somewhat sullen Noel Redding (whose bass parts were frequently done by Hendrix on this album) as well as manager Chas Chandler, Jack Casady, drummer/friend Buddy Miles (later of Band of Gypsys) and others.

It is fascinating and adds another dimension to the music.

It seems a shame then that the repackaging didn't finally conform to Hendrix's wishes -- explicity expressed in a letter reproduced in the booklet.

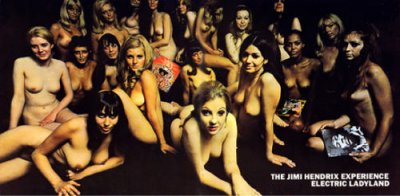

He wanted a Linda Eastman photo of the band with a bunch of children in Central Park on the cover, instead the record company chose a blurry headshot or, more controversially in England, Track Records put it out with a spread of partially clad women on the gatefold -- which Hendrix hated.

In New Zealand it came out in a single sleeve with a glorious technicolour photo by David Montgomery (below) which, for my money, was the best of the lot and a classic shot.

The Eastman shot is used on the inside sleeve of the repackaged album, and there is also a booklet with an essay by the late Derek Taylor.

With the death of Mitchell late in 2008 there are now no longer any remaining members of The Jimi Hendrix Experience -- but their legacy, and most particularly that of the guitar shaman Jimi Hendrix, is still there for anyone to appreciate and attempt to assimilate.

Electric Ladyland offers an enormous amount of music, possibilities and, best of all, pleasure.

As with that debut, Hendrix opened a door onto a new landscape and let others look at it.

But when he left he closed it behind him.

These Essential Elsewhere pages deliberately point to albums which you might not have thought of, or have even heard . . .

But they might just open a door into a new kind of music, or an artist you didn't know of. Or someone you may have thought was just plain boring.

But here is the way into a new/interesting/different music . . .

Jump in.

The deep end won't be out of your depth . . .

Evan - Apr 12, 2009

Great blog post on Electric Ladyland. What most people don't know is that there are so many other songs he recorded and was working on like Valleys of Neptune, Heaven Has No Sorrow, etc. Keep up the great work.

SavetonyH - May 9, 2009

Thanks for rekindling the Hendrix flame. Full respect for Electric Ladyland and Are You Experienced, but I couldn't sit by and allow my favourite JHE album to be dismissed as "pallid". Stuck here in Qatar for a few months without having had time to rip a few LPs before leaving NZ, I needed no further excuse to grab Axis: Bold as Love from iTunes to check if nostalgia is clouding my appreciation, and I wasn't disappointed. Ladyland was my first taste of Hendrix magic, sustaining me through a winter in a windowless basement on Constitution Hill, reeling to Gypsy Eyes, Crosstown Traffic and of course the Rainy Day, Dream Away side (have you tried cutting and pasting Still Raining, Still Dreaming onto the cadence before the start of the wah-wah on Rainy Day - they are the same track and reunite well!), though I still find the signature Hendrix blues sound in both Voodoo Chile variants muddy and over-heavy. I came to Are You Experienced later, but it's also full of well-loved tracks, particularly Red House (a purer blues treatment), I Don't Live Today and Love or Confusion. But it was Axis that packed a wallop I still feel, no doubt helped at the time by appropriate substances (but that was equally the case with the other albums). From the Hinduesque cover art and the overt manifesto of Up From the Skies ("...this here people farm..."), to the warp-drive finale solo of the title track, this was the package that convinced my spec-fiction-soaked mind that Jimi was a (perhaps unwitting) avatar from an enlightened alien culture, or at least some sort of musical equivalent of William Blake. Decades of continued SF addiction haven't exactly disabused me; the question remains as to where his sustained creative burst appeared from after an admittedly pallid early career as a sideman. The album abounds with seductive mysticism (lady cloudwalkers, a golden-winged ship, an all-knowing Axis being). But whether or not you are dazzled by the sometimes far-out, sometimes down-to-earth lyrics, the music and Hendrix's continuing mastery of the studio stand out. The easy jazz of Up From the Skies (a worthy precursor of Rainy Day), the shifting time-signatures right up to the end of Ain't No Telling, the nuanced wah-wah and backwards guitar in Castles Made of Sand", the beautifully balanced construction of that and the title track, the often-covered melody of Little Wing, the contrast of grace and power in One Rainy Wish.

SaveLike most albums it has patchy moments (Little Miss Lover, You Got me Floatin' - but maybe that's just me), but even Mitchell and Raedding are as cohesive a unit as they ever were; Jimi's frenetic guitar overlay and solo on She's So Fine lifts an othewise almost pallid track. No, after careful reacquaintance I can't discern any faltering creativity here. Hendrix was a towering but flawed genius; to my ear this is his most consistent and nuanced work, never forgetting all the other highlights from Hey Joe through to posthumous gems like My Friend and Drifting.

Enough rant! Do have another listen if you get time. I remain in awe of your output, a lifeline here in the desert, wish there was time to listen to everything!

post a comment