Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Frank Sinatra: Ill Wind

Some may remember it, that strange time when we were told that Tony Bennett was hip with the grunge crowd. It seemed unlikely (I doubted it) but it at least gave me the opportunity to interview him and he was, of course, positively charming as you might have expected.

Quite why anyone would prefer Tony Bennett over Frank Sinatra was always the question, especially the so-called dissenting and disaffected young of the grunge crowd.

Frank had it all: ineffable cool, Mob connections, a string of beautiful lovers, personal drama, unspecified rage, sullenness, a mean and violent streak . . . Tony smiled and did oil paintings in his apartment overlooking Central Park.

But by the late grunge era Sinatra was a forgotten man. His best years were decades behind him, his life reduced to crayon sketches of punch-ups, the Mia Farrow years and Mafia stories, his acting career was on late-night re-run where you sometimes wondered what had ever been the attraction of that skinny guy . . .

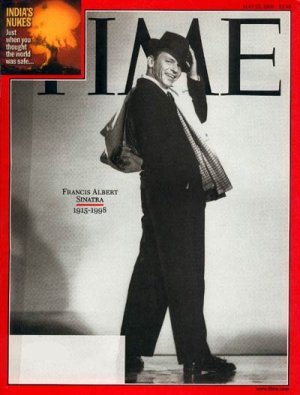

Yet Sinatra was an American icon like few others, a man above and beyond the world of mere mortals it seemed, and when he died the Time magazine cover didn't even require an explanatory sub-heading: it just read "Francis Albert Sinatra 1915-1998".

Yet Sinatra was an American icon like few others, a man above and beyond the world of mere mortals it seemed, and when he died the Time magazine cover didn't even require an explanatory sub-heading: it just read "Francis Albert Sinatra 1915-1998".

Frank Sinatra had a number of careers: he'd enjoyed the equivalent of Beatlemania in the early Forties but times changed; during the war he won the hearts of women with absent boyfriends and husbands; but in the late Forties -- despite a successful movie career -- he could no longer sing as he did and the young audience was of little interest to him any more. (It waned when the boyfriends/husbands came home.)

He played Las Vegas, made more films (among them the excellent From Here to Eternity for which he won and Oscar) but his record sales fell steadily. The affair with Ava Gardner brought him into disrepute and he was the subject of derision.

Time to reinvent himself, and his new label Capitol -- which only offered him a year-long contract and made him pay his own studio costs -- allowed him, possibly a last chance, to do that.

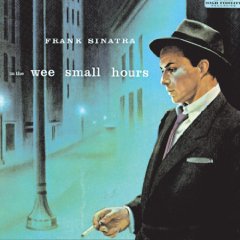

It seems odd now to reflect that In the Wee Small Hours was only his second LP, but Sinatra and arranger Nelson Riddle understood the longer running format: they pulled together a collection of songs around the loose theme of the hurting loner who has been unlucky in love, and even though a number of them had been a round a while Sinatra and Riddle created a sustained mood piece in which to integrate them.

With what seemed like an ease and almost ennui, he redefined ballad singing and, as Mikal Gilmore notes in Night Beat: A Shadow History of Rock & Roll, "staked out a vocal sensibility that would become the hallmark of his mature style, and that would establish him as the most gifted interpretive vocalist to emerge in pop or jazz since Billie Holiday".

Sinatra took on these songs right from the heart and inhabited them like an actor. Not that he was acting much. His affair with, then marriage to, Gardner had been volatile and had hurt them both. Sinatra knew those deep and dark times when you were alone with a bottle and bad memories -- and he turned it into art.

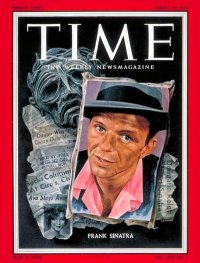

A few months after the album was released he was on the cover of Time and the article noted of him and his art, "You might as well try to analyse electricity. He is what he does."

A few months after the album was released he was on the cover of Time and the article noted of him and his art, "You might as well try to analyse electricity. He is what he does."

Sinatra had merged with his art, the character in the song was the one he believed in, the one who spoke through him.

"Having lived a life of violent emotional contradictions," he would say much later, "I have an overacute capacity for sadness as well as elation . . . when I sing, I believe."

As industry veteran and longtime Warner Bros execuctive (and king of the liner notes) Stan Cornyn said later, "For all his crashing self-assertion, through his art he was suggesting that man is still only a child, frightened and whimpering in the dark".

Riddle's arrangements are present but discreet and supportive, however what is central is Sinatra's phrasing where he delivers the lyrics as if reading a story. These are not merely lines to be sung, but words to give weight and depth and meaning to.

"I've always believed that the written word is first, always first," he said. "Not belittling the music behind me, it's really only a curtain. You must look at the lyric and understand it. Find out where you want to accent something, where you want to use a soft tone. The word actually dictates to you in a song, it really tells you wahat it needs."

On this album, where his voice had matured and sounded darker, he began to take liberties with timing, sometimes just ahead and sometimes just behind the beat.

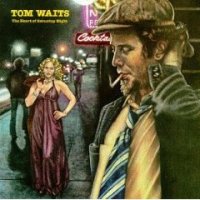

These were songs that took their place in people's lives: In the Wee Small Hours is Tom Waits' favourite Sinatra album and he modelled his own Heart of Saturday Night album cover on it; jazz saxophonist Lester Young started to include When Your Lover Has Gone in his sets; and Billie Holiday repayed the compliment of him borrowing from her by covering songs Sinatra had done.

These were songs that took their place in people's lives: In the Wee Small Hours is Tom Waits' favourite Sinatra album and he modelled his own Heart of Saturday Night album cover on it; jazz saxophonist Lester Young started to include When Your Lover Has Gone in his sets; and Billie Holiday repayed the compliment of him borrowing from her by covering songs Sinatra had done.

Frank re-recorded It Never Entered My Mind for the album (he'd done it '47) after hearing Miles Davis' more mature version -- and Davis, a Sinatra fan, went on to play other songs from Sinatra's catalogue, influenced by the singer's phrasing. A few years later Davis did his own late-night concept album, Kind of Blue.

And closer to home, my mother used to sing I Get Along Without You Very Well ("except of course in summer . . .") in the years after my father's death.

Albums rarely had such a sustained mood -- most albums then and even now are the hits then the padding -- but here Sinatra not only reinvented himself but laid out the possibilities for how an album of popular music could sound, and what it could mean. He discovered a sense of "aloneness" within himself and gave it up for scrutiny.

The unattributed liner notes about these sessions say, "Standing in front of the mike with his hands nearly always jammed into his pockers, his shoulders hunched a little forward, he sang. And as he sang, he created the loneliest early-morning mood in the world."

These Essential Elsewhere pages deliberately point to albums which you might not have thought of, or have even heard . . .

But they might just open a door into a new kind of music, or an artist you didn't know of.

Or someone you may have thought was just plain boring.

But here is the way into a new/interesting/different music . . .

Jump in.

The deep end won't be out of your depth . . .

GF - Feb 16, 2010

1957's Close to You, recorded with the Hollywood string quartet, is also a very fine record, and often over-looked among Frank's great 50s albums.

SaveContains a lovely version of Everything Happens To Me.

post a comment