Graham Reid | | 4 min read

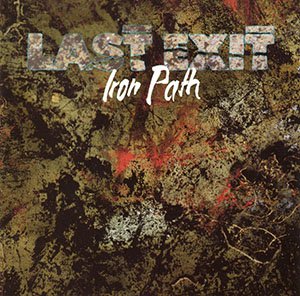

Last Exit: Devil's Rain

When this album was recorded in the late Eighties, free jazz had been largely consigned to the "blind alley" by jazz writers.

By then mainstream American jazz critics had been foolishly distracted and seduced into exercising themselves into the whole neo-con debate which Wynton Marsalis and his acolytes (remember them?) had wrought upon jazz.

At the time there was one of those enduringly stupid "What is jazz?" arguments in which the arrogant, presentable, good-looking and (I have to say very engaging when I met him) young Wynton Marsalis shoved some arbitrary Ellington/pre-Sixties Miles Davis stakes into the ground.

Free jazz then became just one those embarrassing things -- like fusion -- which had happened in the Seventies when certain players extended to contract of freedom of expression to its logical conclusion.

That free jazz during the late Sixties and Seventies in the States had large dollops of black politics about it perhaps didn't help . . . and certainly alienated many white writers who, in the language of previous generations, thought these black were gettin' jes a little uppity.

But free jazz brought to the fore some astonishing artists and ideologies, not the least the Art Ensemble of Chicago, the extraordinary Revolutionary Ensemble and its individual offshoots . . . and then of course those household names like Jemeel Moondoc, Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre and Longineu Parsons.

Interestingly enough, or ironically if you prefer, over in Europe a whole other school of free jazz emerged because Germans like Peter Brotzmann were fighting their own battles for freedom as their East/West divide went head-to-head . . . and the children of the fascist regimes of the Second World War confronted not just their past but their present.

For them freedom meant no going back. As it did for many of those black American artists who felt exactly the same in the post-MLK/Malcolm X era.

And so inevitable the twain should meet.

Last Exit was a powerful, loud, angry and incendiary post-Hendrix/post-free jazz implosion of similarly inclined political and emotional musical forces: from the US drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson, shredding guitarist Sonny Sharrock and bassist/producer/enabler Bill Laswell . . . and then Brotzmann.

And this debut -- their sole studio album, which makes sense because they were a spontaneous combustion and live explosion -- pulled the fury into one place. The titles of the pieces -- all improvs of course -- came as The Black Bat, Marked For Death, The Fire Drum, Detonator, Cut and Run, Eye Fort An Eye, Devils' Rain . . .

Hmmm, do you feel me?

Hmmm, do you feel me?

But here's the thing.

Last Exit connected in a way few other free jazz/post-punk improv bands did because there was an audience in the mid Eighties for volume and vehemence, pure noise, rage and ...

Consider this: Laswell had been involved with everyone from Iggy Pop, Motorhead and Herbie Hancock to John Lydon with Afrika Bambaataa . . . and his Celluloid label had embraced Sharrock, Archie ("let my notes be bullets") Shepp, avant-guitarist Fred Frith and the Golden Palominos.

Just five years previous he'd produced/instigated Herbie Hancock's Future Shock album, much of which he co-wrote . . . including the breakout turntable single Rockit.

And let's not get started on Brotzmann whose Machine Gun of '68 aggro-political-fist-in-face sound not only encapsulated a raging mood and the zeitgeist in a divided Europe but became the gold standard for free, lung-abusing saxophone blowing . . .

Or how guitarist Sharrock who came through Pharoah Sanders bands and was one of the uncredited players on Miles Davis' Jack Johnson sesions; and drummer Jackson (from Ornette Coleman's hometown of Fort Worth) had hooked in the NYC avant-garde in the Sixties (and played with Mingus, Joe Henderson, McCoy Tyner etc) before forming his own furious Decoding Society in the Seventies.

Fair to say we have a free jazz supergroup here in Last Exi?

Fair to say we have a free jazz supergroup here in Last Exi?

And that the sheer attack found better favour with open-eared alt.rock audiences than in jazz?

No matter what side of the Marsalis/neo-con debate you were on at the time, you'd probably agree that Iron Path was damaging, incendiary noise, and you would not want to subject you sensitive ears to the assault that is Devil's Rain . . . which sounds just right for Sonic Youth fans (despite what you might hear as a massive glam-rock riff lurking in the mid-ground).

Iron Path is a bawdy, bellicose, wildly swinging brawler of an album . . . it is what is, and wasn't polite at the time.

Or even is now.

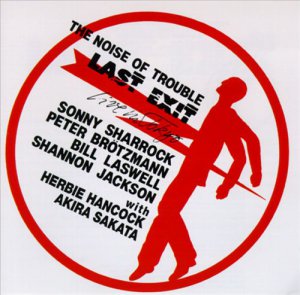

It was enough however for me to get out and import -- in those pre-internet/download/easy access days -- their live albums like The Noise of Trouble recorded in Japan a couple of years later.

Herbie Hancock and Japanese-out-there saxist Akira Sakata found time to appear with Last Exit at the time.

Herbie Hancock and Japanese-out-there saxist Akira Sakata found time to appear with Last Exit at the time.

And if it is good enough for Herbie and Akira . . .

Be sure to buckle your seatbelt for Iron Path.

However: This album does not seem to be available on iTunes or Spotify, but is available through Amazon. Not cheap though.

But it's a rare one. Worth locating.

These Essential Elsewhere pages deliberately point to albums which you might not have thought of, or have even heard . . .

But they might just open a door into a new kind of music, or an artist you didn't know of.

Or someone you may have thought was just plain boring.

But here is the way into a new/interesting/different music . . .

Jump in.

The deep end won't be out of your depth . . .

Graham Dunster - Jan 29, 2015

There it is sitting on the shelf, a remnant from all the vinyl clearouts in Sounds in the 90s. If it was on Venture they were giving it away (in hindsight). Maybe I'll get round to playing it now!

Savepost a comment