Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Frank Sinatra: It's a Lonesome Old Town

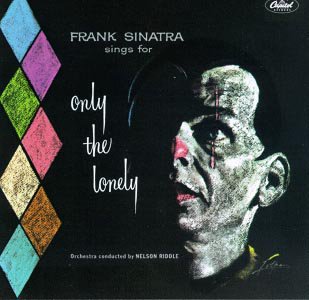

Although neither his best known long playing record from the era (the LP format was just kicking off) nor his biggest seller of the late Fifties, Frank Sinatra's Only the Lonely is an outstanding collection of themed songs.

His best known albums from this period are In the Wee Small Hours from '55 (long an Essential Elsewhere album), Songs for Swinging Lovers! and Come Fly With Me (all of which preceded Only the Lonely).

His biggest seller was the more upbeat Come Dance With Me! which followed it.

That said, Only the Lonely topped the Billboard charts (Come Dance only made it to number two) and stayed on the charts for 120 weeks.

When Sinatra – who had recorded 11 albums in the five years before Dance, made a few movies, done television specials and series, and had toured – attended the inaugural Grammy awards in May '59 (for the '58 year), he was nominated for six awards, among them two in the best album category, for Come Fly With Me and Only the Lonely.

Despite the winds of acclaim behind him, he picked up only one award, for (nominally) being the art director for Only the Lonely (the sad clown painting was by Nicholas Volpe) in the best cover category.

In the second part of his meticulously researched biography (if sometimes repetitively phrased) of Frank Sinatra, Sinatra; The Chairman (which followed Frank; The Voice), writer James Kaplan says 43-year old Sinatra started drinking immediately the ceremony was over, took his date (the young, strictly B-grade actress Sandra Giles, then in her mid 20s) back to his house and they woke up naked together the following morning.

“He claimed they had sex; she was

sure they hadn't,” Kaplan writes. “She locked herself in the

bathroom and told him she was going to call the police. He talked her

out of it . . . .”

Later she found a $US100 note in her purse

from Frank which he told her was to buy her daughter a Christmas

present.

“It was his way of apologising,”

said Giles (pictured) later. “He never actually said he was sorry.”

“It was his way of apologising,”

said Giles (pictured) later. “He never actually said he was sorry.”

And in that 24 hour period – the highs, the lows, the booze, the presentable but disposable broad, the unapologetic chairman of the board – you have some encapsulation of what Sinatra's life was like, especially from the mid Fifties until almost the middle of the following decade.

He was volatile, easily bored (which is why he worked constantly), and while frequently acclaimed was also often snubbed by those who admired, loathed or were afraid of him.

And often he moved on fast.

At the end of the week of the Grammys he was back recording – again with the great Nelson Riddle who arranged and orchestrated the songs on Only the Lonely. One of the songs he recorded was the buoyant, chart-bothering song of optimism, High Hopes.

As Kaplan notes, Sinatra often recorded “a sad or contemplative LP alternating with a brisk and bouncy one”.

Only the Lonely – which is a close cousin to the '57 torch song album Where Are You, the songs there arranged and conducted by Gordon Jenkins who Sinatra initially wanted for Only the Lonely – is one of his saddest and most contemplative.

Some of the titles tell you as much: Only the Lonely, It's a Lonesome Old Town, Willow Weep For Me, Goodbye, Blues in the Night, I Guess I'll Hang out My Tears to Dry, Ebb Tide, Gone with the Wind and a song he revisited from earlier in his career, the signature 2.45am ballad One for My Baby (And One More For the Road).

If the titles and front cover didn't alert you to the contents, then the back cover – a sketch of a man on a park bench seen from above and beneath a lamp-post – drove the point home.

If Sinatra was indeed the art director, he knew the message he wanted to convey.

And his gift of course was – whatever you made of the man's private life – he could inhabit a lyric like no other, as he does on this album. You believe him to be the lonely one who has lost his love and perhaps his passion for life.

As Don Costa, who produced the '62 album Sinatra And Strings put it: “His reading lyrically is far better than anyone I have ever heard, it's almost flawless.”

Sinatra himself said, “Whatever else has been said about me is unimportant. When I sing, I believe I'm honest.” (Actually he didn't say it, the quote came from a Playboy interview which Frank's PR/adman Mike Shore wrote: questions and answers.)

He also said it was about the lyrics and the music was just a curtain.

But, with arrangers like Nelson Riddle (pictured) and Gordon Jenkins especially, he had wonderful curtains behind him.

But, with arrangers like Nelson Riddle (pictured) and Gordon Jenkins especially, he had wonderful curtains behind him.

For these quick sessions – six of the 11 songs in two nights, five in another session – Riddle arranged charts which supported the singer (the soar of strings then silence on Gone With the Wind) or kept a discreet distance (the spare arrangement of One For My Baby which is mostly just Sinatra and his longtime session pianist Bill Millar in the opening section which establishes the mood and narrative).

The album begins with what might seem high drama from piano and warm strings until that curtain pulls back and Sinatra steps out with barely an instrument behind him.

When on Angel Eyes he opens with an assertive “Hey drink up all you people, and order anything you see” Sinatra's tone suggests that he can't be in any celebratory mood because “my angel eyes ain't here”.

Trumpeter Harry Edison (known for his work with Count Basie's bands and with Ella Fitzgerald, whom Sinatra considered the greatest singer of his generation) brings a distant, blues melancholy to Willow Weep For Me alongside the mournful strings as Sinatra effortlessly stretches the notes, a masterclass in how to play with tempo and delivery of lyrics.

Sinatra oozes an effortless confidence everywhere on the album at a time when he might have been a dominant figure in the mainstream musical landscape but was being assailed by the emergence of rock'n'roll and stars like Elvis Presley.

Sinatra had no time for that music: “It fosters almost totally negative and destructive reactions in young people,” he'd said while also describing rock'n'roll as “the most brutal, ugly, degenerate, vicious form of expression it has been my displeasure to hear”.

He described rock'n'roll singers and their audience as “cretinous goons”.

At his age, coming from his big band background and having graduated into an artist for a sophisticate middle-class audience, Sinatra could hardly be expected to warm to a genre that at worst was degenerate and at best might replace him.

But it didn't.

But it didn't.

His albums continued to sell (to come would be No One Cares, which is like the third in a trilogy after Where Are You? and Only the Lonely) and of course further down the track would be Strangers in the Night (which he hated) and many other better and lesser moments.

To give it its full title, Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely, is a great album to listen to in any period . . . and not because Q magazine writers voted it the number one on their list of the 15th Greatest Stoner Albums of All Time.

In fact, if you are stoned, you won't get it.

In the Seventies when he was asked his favourite album, it was the one he chose.

“Spring is here . . . why doesn't my heart go dancing?” he sings on the Rodgers and Hart number Spring is Here. “Maybe because nobody loves me . . . “ he yearns.

And – especially if you know his mood at the time after his lengthy separation then recent divorce from his wife Ava Gardner, whom he was obsessed with and whose departure fed and reinforced his emotional emptiness within – you believe him.

He did loneliness and – ironically, for a man who seemed to have few – regret better than anyone.

post a comment