Graham Reid | | 3 min read

A Quivering Leaf, Ask the Winds

Vangelis had a pointed comment about the vacuous New Age music which emerged in the late Seventies and reached epidemic proportions in the Eighties.

He said it “gave the opportunity for untalented people to make very boring music”.

Many people said much worse about it because this was music which was often mere sound designed not to be listened to but just to offer some immersive experience during yoga or massage sessions.

Certainly some New Age music had a higher purpose, a kind of spiritual enlightenment – albeit attached to no particular philosophy or religion – and if it served to make people relax then, like meditation, it served some purpose.

It was in the purest sense, feel good music.

But for a very long time it seemed that anyone with access to an acoustic guitar, piano or synthesisers could create shapeless sounds of no special interest or structure, and market it through New Age bookstores alongside the latest diet-fad recipes and books by converts to whatever Eastern philosophy was in vogue.

The Windham Hill label was often associated with New Age music but many of their artists – pianist George Winston, composer Mark Isham (who went on to play on numerous soundtracks) and guitarist David Torn (who worked with Bowie, David Sylvain and record now for ECM) – created something more than Teflon sounds which aimed to do nothing more than fill the air.

New Age music certainly had its ancestors in the ambient music of Brian Eno and the “furniture music” of the early 20th century (a term apparently coined by Erik Satie to describe some of his background music pieces).

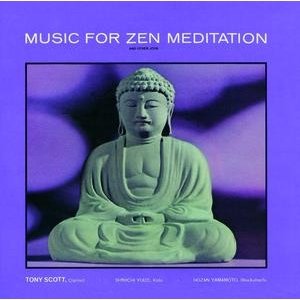

The more gentle end of the minimalist school might also be cited but many writers point to Music for Zen Meditation by the American clarinetist Tony Scott, koto player Shinichi Yuizke and Hōzan Yamamoto (shakuhachi, Japanese bamboo flute) as the first true example of spiritually-inclined New Age music.

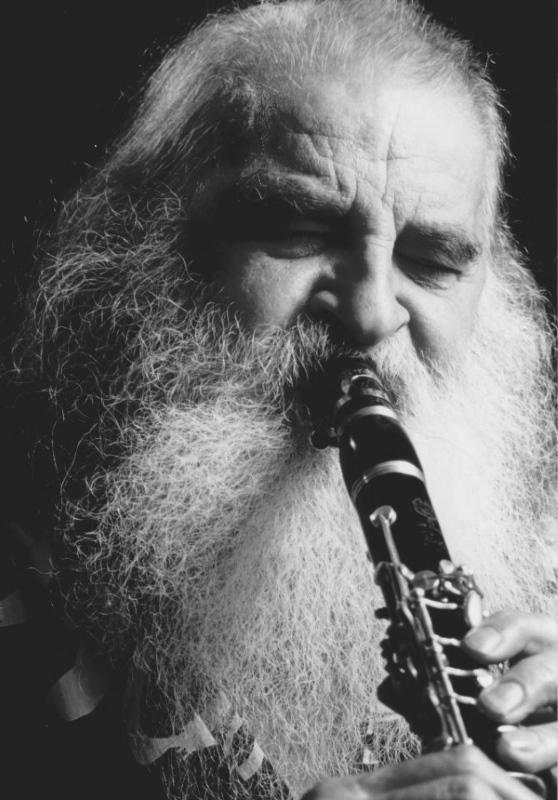

Scott was in his early Forties at the time, had come up through Juilliard, was a multiple winner of Downbeat awards and was considered by Leonard Feather to be “among the new true masters in contemporary jazz”.

He'd played with Sarah Vaughan and Billie Holiday in the Fifties by by the end of that decade was spending more time in what was then called “the far East”) Japan, Okinawa, Thailand where he played command performances for the King, Hong Kong and so on.

He became increasingly interested in the folk music traditions in these places and was drawn to Zen practices in Japan where he stayed for three months in the early Sixties.

He had met Yuize in '59 when he was

recording some traditional music for a radio programme and asked him

if he could improvise on koto. (He could although improvisation was

not a part of the Japanese classical tradition, but he'd started

learning koto at age three and had been composing since he was six.)

He had met Yuize in '59 when he was

recording some traditional music for a radio programme and asked him

if he could improvise on koto. (He could although improvisation was

not a part of the Japanese classical tradition, but he'd started

learning koto at age three and had been composing since he was six.)

It was the start of a close association but remarkably, all the nine pieces on Music for Zen Meditation was the only time they recorded together and all the pieces were improvised.

With clarinet and shakuhachi floating almost weightless above the soft plucked strings of the koto, this is elevating spiritual music which reaches back through a long tradition of Japanese music.

In Scott's liner notes he describes Yamamoto's solo – presumably that on the opening piece Is Not All One? – as “the most soulful and complete musical piece I have ever heard”.

In subsequent years a number of other jazz musicians embraced various spiritual or meditative practices, notably flute player Paul Horn who would record inside the Taj Mahal and other such sites.

And Horn was there in Rishikesh with the Beatles in the late Sixties.

But while the Beatles were still playing A Hard Day's Night and Horn was working with large ensembles and playing standards, Tony Scott was already on a journey of his own with Music for Zen Meditation which would lead to albums of yoga-inspired music, with Indonesian musicians and beyond.

So, not New Age music as you might expect but something emotionally deeper, more grounded and thoughtful.

You might even call it soul music.

.

You can hear this album on Spotify here

.

These Essential Elsewhere pages deliberately point to albums which you might not have thought of, or have even heard . . .

But they might just open a door into a new kind of music, or an artist you didn't know of.

Jump in.

The deep end won't be out of your depth . . .

post a comment