Graham Reid | | 5 min read

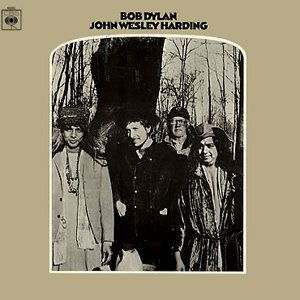

All Along the Watchtower

There are of course many albums by Bob Dylan which would immediately go into an Essential Elsewhere list: All of those in that remarkable 18-months recorded between January 1965 and July 1966 (Bringing It Al Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and the double album Blonde on Blonde); Blood on the Tracks ('74), “Love and Theft” and Modern Times in the early 2000s which signalled a new and different beginning . . .

And these days you could list some of the on-going Bootleg Series because a number of them are extraordinary, not the least the most recent collection of his much maligned “Christian trilogy”.

But our attention here alights on an album that was so far removed from the zeitgeist of the period and so very different in his catalogue that it demanded Bob Dylan be re-thought . . and in some ways opened the door for Americana, prepared the ground of the Basement Tapes and even the sleight of hand story-telling of Blood on the Tracks.

John Wesley Harding – its title a typically Dylan aberration of a historical character's name (see William Zantzinger in The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll as “Zanzinger”) – arrived at the end of a year when the Beatles had captured and defined the idea of eccentric British hippiedom and the Summer of Love with Sgt Pepper's and the single All You Need is Love.

Peace, love and incense was in the air and yet, to paraphrase David Crosby, somehow Sgt Pepper's didn't stop the war in Vietnam.

Musicians in that year when the Doors, Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix (among others) were towering over the landscape thought it was possible that “when the mode of the music changes, the walls of the city shake” (to quote the Fugs quoting Allen Ginsberg).

And where was the man who had been tagged “the spokesman of a generation” and “a leader”?

Bob Dylan had retreated to domesticity, was enjoying family time, retired himself from the mayhem of the previous three years and using a motorcycle accident to become a “recluse” in upstate New York.

Of course he wasn't a recluse, he just wasn't saying anything or releasing records. He would walk his step-daughter to school, had good relations with his neighbours and the local police (who would protect his privacy because they kinda liked him), had coffee in the local cafe and was taking painting lessons.

He was also reading voraciously and so, when he did return to a recording studio, despite having various members of what became The Band nearby and with whom he was jamming, he did something typically unexpected.

He went into a Nashville studio with a bunch of already prepared lyrics (Blonde on Blonde and its predecessors had been recorded on the fly with scraps of words) and made a lowkey collection of songs – about as far removed from “peace and love” as you could imagine – with Pete Drake on pedal steel. Drummer Kenny Buttrey said the album was done and mixed in six hours.

"Every artist in the world was in the studio trying to make the biggest-sounding record they possiby could," said producer Bob Johnston. "So what does he do? He comes to Nashville and tells me he wants to record with a bass, drum and guitar."

The stripped back songs – as with Positively Fourth Street and others beforehand – were mostly without choruses and were steeped in religious imagery.

In his study The Bible in the Lyrics of Bob Dylan, researcher Bert Carter finds 61 references or allusions to the Old and New Testaments on the album.

Alongside this however was the idea of the outlaw/outsider hero . . . a figure Dylan had encountered as a teenager in anti-hero movies like The Wild Ones and Rebel Without A Cause but whom he increasingly located in the Old West.

And of course this was a character he would subsequently embrace in Sam Peckinpah's shapelessly violent film Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid in which Dylan played the mumbling and visibly uncomfortable character Alias, and he gifted the film a soundtrack better than it deserved (with the hit Knocking on Heaven's Door).

In the broad sweep of Dylan's vast catalogue (almost 40 studio albums), John Wesley Harding is one which seems to have been passed over in favour of the early work and Blood on the Tracks.

But it contains insightful and mysteriously deep songs, looked back to his folk roots (I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine riffs off the old ballad I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night which Dylan's former paramour Joan Baez would sing at Woodstock, a festival which Dylan pointedly did not attend) and of course Jimi Hendrix – and avid fan of Dylan's writing and singing – made a massive psychedelic/hard rock cover of All Along the Watchtower (lyrics drawn from Isaiah).

It is a song which ends just when the story seems to start going with the mysterious riders approaching in a howling wind. When he toured again he would perform it in a manner more akin to Hendrix's version.

It is also an album full of romantic imagery (the title character was a killer outlaw in real life but in Dylan's hands more like the gallant Robin Hood), allusions to real characters and mythological figures, narrative misdirection, a look back musically to his folk roots but also ahead into directions he would explore in mainstream ballads.

He goes back to old Anglo-folk tropes of love and death on As I Went Out One Morning, the ancestor of the gorgeous Belle Isle on Self Portrait, and includes a reference to the journalist Tom Paine) and the story, if that's what it is, goes unresolved, again the preamble to what might happen later.

And he sings so well on songs like Dear Landlord and the closing track I'll Be Your Baby Tonight.

Those looking for clues into Dylan's private life might have been rewarded too: Is his Dear Landlord about the simmering dispute with his manager Albert Grossman who he'd discovered was taking a 50 percent cut in the contract?. Was Grossman the Judas who put money on the footstool in The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest? “Judas he just winked and said, 'Alright, I'll leave you here but you better hurry up and choose which of those bills you want before they all disappear”.

It's a long parable full of contradictions, blind alleys, allusions and a faux-moral.

I Pity the Poor Immigrant him looking back to those years – just five previous – when he was a Woody Guthrie acolyte and shoplifting his mantel as a working class hero? And Wody had just died around this time, Dylan making a rare public appearance when he played a Guthrie tribute concert in January '68.

Questions and questions, and importantly no answers.

And was Dylan the drifter” who escaped?

Metaphors and metaphors, and importantly no answers.

And All Along the Watchtower? What century is that set in?

The Dylan mysteries and myths sketched out of John Wesley Harding became a continuum. It was an album out of time which is why it still engages today. It is musically simple but lyrically deep, it is serious and playful.

As Jon Landau noted in Crawdaddy at the time, “Dylan seems to feel no need to respond to the predominant trends in pop music at all. The Dylan of John Wesley Harding is a truly independent artist who doesn't feel responsible to anyone else, whether they be fans or his contemporaries”.

These Essential Elsewhere pages deliberately point to albums which you might not have thought of, or have even heard . . .

But they might just open a door into a new kind of music, or an artist you didn't know of. Or someone you may have thought was just plain boring.

But here is the way into a new/interesting/different music . . .

Jump in.

The deep end won't be out of your depth . . .

Jeffrey Paparoa Holman - Jul 8, 2018

Kia ora Graham

SaveOnce again you send me back to think about Bob from another angle. Thank you. I'm finalising edits on a new memoir where my relationship with his music figures in an early chapter. Always something to learn.

Enjoy your break, roll on August.

Cheers Jeffrey

post a comment