Graham Reid | | 11 min read

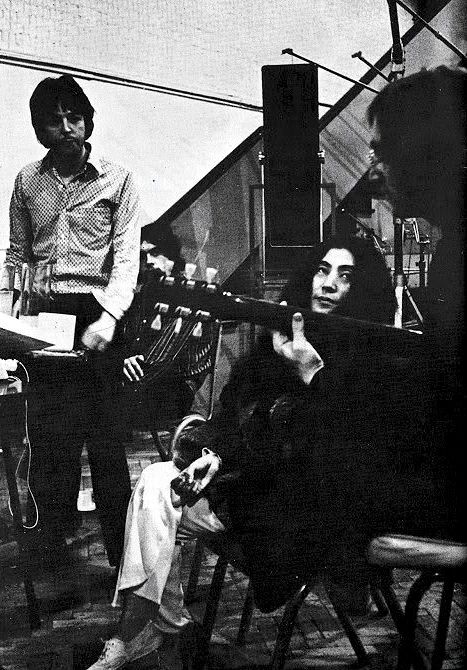

Good Night rehearsal

Half a century ago when The White Album appeared, large parts of the Western world and beyond seemed to be tearing themselves apart, just six months on from the incense'n'marijuana whiff of the Summer of Love.

1968 began badly and got worse: During the Tet Offensive in January Vietcong insurgents rose up all over South Vietnam and one unit got into the grounds of the US Embassy in Saigon; the student demonstrations in Paris spread when workers joined them and there was a general strike which almost brought down the government; anti-Vietnam demonstrations were everywhere including in Grosvenor Square in London . . .

There were the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy; the rise of the Black Panthers; the imprisonment of Panther founder Huey Newton on murder charges and their Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver fleeing to Cuba after a shoot-out with the police in Oakland . . .

By any measure 1968 was a helluva mess.

It was the year that changed the world according to writer Mark Kurlansky.

It's hard to think of any other in the 20thcentury – other than those where world wars were declared and fought – which was quite so volatile and literally explosive.

Everywhere you could hear the sound of marching chanting people, to paraphrase Mick Jagger in Street Fighting Man. But that Stones' song was much more equivocal than its angry sound suggested. Jagger – who had briefly joined the Grosvenor Square march, long enough to get his photo taken before getting back in the Bentley – also shrugged: “But what can a poor boy do, except sing in a rock'n'roll band . . .”

If the revolution in the streets had inspired him it wasn't enough to engage his services.

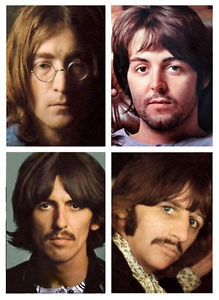

And what of the Beatles, the figurehead band of the Sixties which had articulated and exemplified the hippie/Summer of Love period with Sgt Pepper's back in June '67 and followed it up with the anthemic All You Need is Love just weeks later?

Where were they in this volatile period?

Well, as this dark and dangerous year opened they headed for remote Rishikesh in the Himalayan foothills of India for a meditation retreat with the Maharishi Mahesh Yoga. And holed up there, literally well above the fray, they – with the exception of Ringo who quit early – spent weeks and weeks there eschewing drugs, eating well, meditating and . . .

Of course, writing music.

Of course, writing music.

In the absence of electric guitars, monitors and screaming crowds it was a back to the bedroom acoustic experience. And for what happened next, that made all the difference.

When they returned to Britain – still not engaging with the chaos the year was throwing up – they had a wedge of material for their next album, so much that it would come out in November '68 as a self-titled double, its often stark music and plain cover announcing it as a deliberate retreat from the baroque pop gestures of the previous year and something of an anti-Pepper.

It is just The White Album to everyone.

If there is an album in the Beatle's short catalogue worthy of rediscovery – and one which remains uncharted territory for some due to its vastness, diversity and its lack of hits – it is this one: 30 new songs, 18 of which can be traced to their time in Rishikesh in either theme or style.

If there is an album in the Beatle's short catalogue worthy of rediscovery – and one which remains uncharted territory for some due to its vastness, diversity and its lack of hits – it is this one: 30 new songs, 18 of which can be traced to their time in Rishikesh in either theme or style.

It topped the charts everywhere – that was a given, of course – and critics and fans spent much time decoding the diverse material which ranged from delicate acoustic ballads (Lennon's Julia, McCartney's I Will) to proto-metal (McCartney's Helter Skelter, one of the tracks which inspired Charles Manson's murderous rage) and musique concrete (Lennon's sound collage Revolution 9).

The songs touched on parody (Back in the USSR), humour (The Ballad of Rocky Raccoon), satire (The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill) and nonsense (Why Don't We Do It in the Road?)

The songs touched on parody (Back in the USSR), humour (The Ballad of Rocky Raccoon), satire (The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill) and nonsense (Why Don't We Do It in the Road?)

And more: it gave Harrison three outings (among them While My Guitar Gently Weeps with an uncredited Eric Clapton on guitar, and the gorgeously understated Long Long Long) and even Ringo got in the deliberately cliched but tender ballad in Lennon's Good Night right at the end.

He also had his own composition Don't Pass Me By on the album, a song which took him six years to write.

There was a lot of information on The White Album, its depth and breadth making it the favourite Beatle album for artists as far apart as Kurt Cobain and Blur/Gorillaz' Damon Albarn.

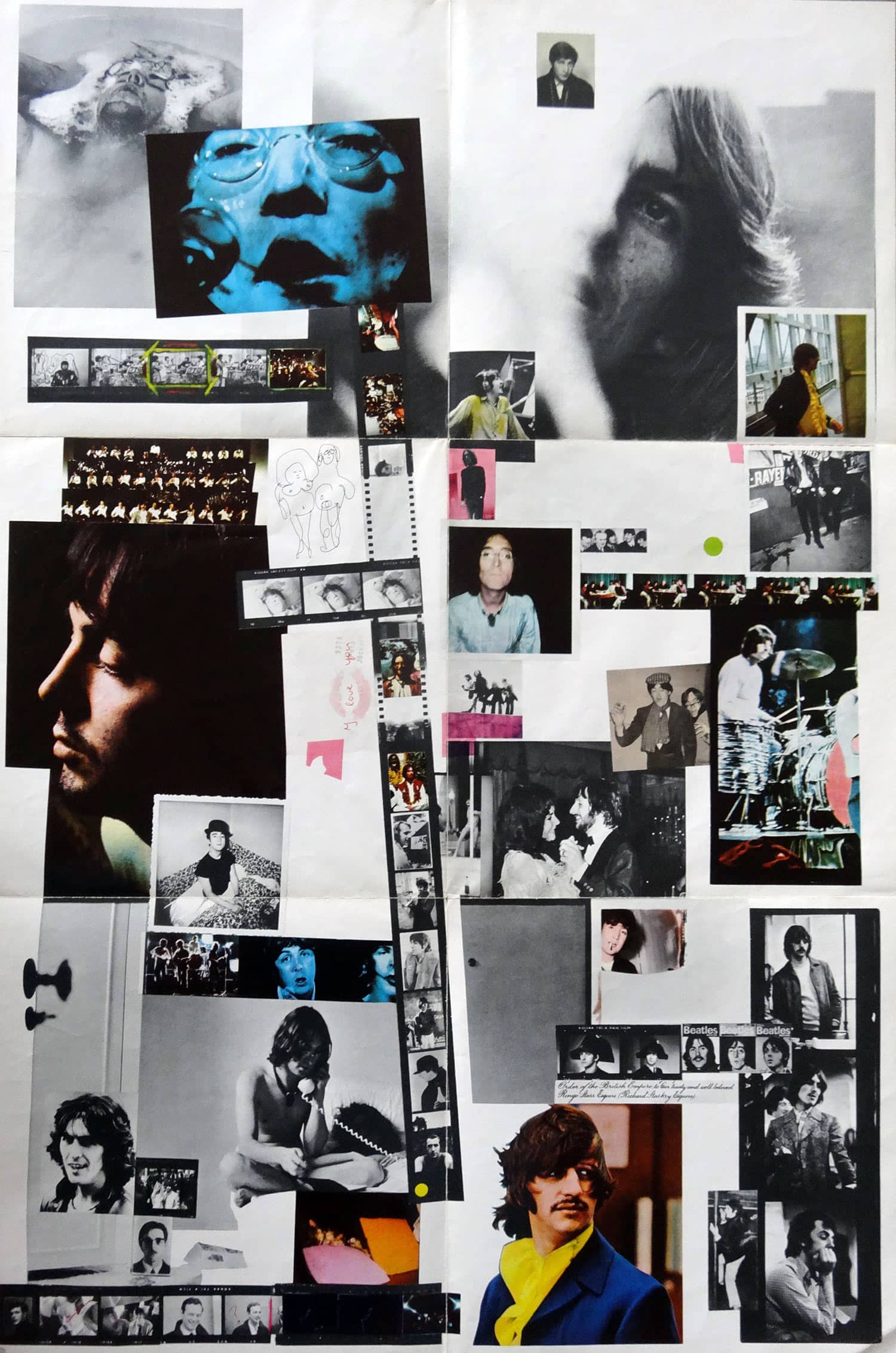

It may have sometimes sounded like a collection of songs by individual Beatles sometimes with others in supporting roles, or even entirely absent: Ringo quit for a while during the sessions, for other sessions various Beatles worked in separate studios. And yet although it might appear the wedge where the group was pulling itself apart, they had previously gathered at George Harrison's home in Esher to demo their songs and seemed to thoroughly enjoy themselves.

If Rishikesh had brought out the more idiosyncratic aspects of the personalities of Lennon, McCartney and Harrison it also put them together in a more relaxed atmosphere than they had experienced for years.

However all of that – the personalities, their increasingly different interests and songs – fed into fractious sessions what became The White Album.

However all of that – the personalities, their increasingly different interests and songs – fed into fractious sessions what became The White Album.

In the studio things sometimes became fraught although there is little recorded evidence in the expanded version (see below).

However Yoko Ono now sat alongside Lennon to the chagrin of the others (Linda Eastman a more discreet presence taking photos); Harrison was stretching himself in his songs (among them that mysterious Long Long Long); Ringo briefly quit, as did engineer Geoff Emerick citing the "toxic" atmosphere, and McCartney's retro-music hall and vacuous pop tendencies were described by Lennon as “Paul's granny shit” . . .

It was however the Beatles' White Album . . . and now it gets a expanded 50thanniversary reissues.

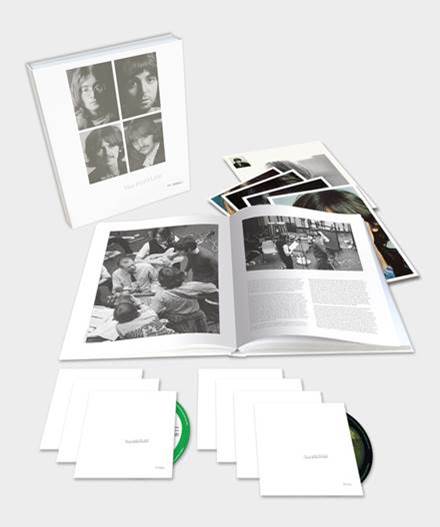

At the lower end of the reissues there is the stereo remix from the original master tapes by Giles Martin (son of original producer George who is now the go-to guy for Beatles reissues) on double-double vinyl and triple CD (the extra disc has the demos from Harrison's home.

At the high end is the seven CD set: The original album in the new stereo mix across two disc, one of 27 Esher demos as well as three more of session and rehearsal takes and a Blu-Ray with the album in high definition 5.1, PCM and mono mixes) With a hardback book of recording details, photos and more.

That's a thumping great set . . . but The White Album is a trove of music, so diffuse and diverse that some critics have taken to describing it as “post modern” when in fact it was just so much music from three writers who'd had time in India and afterwards to write and write. Too much to get onto a single album so . . . Why not?

The songs from Rishikesh include Back in the USSR which parodies both Chuck Berry and the Beach Boys (Beach Boy Mike Love was also in Rishikesh and contributed ideas) and Lennon's plea to Prudence Farrow to stop being so obsessive about meditating and “won't you come out to play” (on Dear Prudence).

An American big game hunter who dropped by at the ashram for downtime between shoots is the subject of Bungalow Bill, and both I Will and Julia were acoustic ballads on guitar, prompted when McCartney and Lennon now had time to explore finger-picking and could get tips from fellow meditator Donovan.

And there was more on The White Album, like Lennon's acerbic Glass Onion, a poke at those who tried to read too much into their lyrics: “Here's another clue for you all, the Walrus was Paul”.

Lennon, who suffered from insomnia because of the meditation, wrote I'm So Tired (which alludes to Yoko Ono back in Britain whom he had become infatuated with and his nicotine withdrawal) and when he learned that the Maharishi had apparently made unwelcome advances toward one of the women penned the bitter Sexy Sadie (“you made a fool of everyone”). It was originally titled Maharishi.

Lennon, who suffered from insomnia because of the meditation, wrote I'm So Tired (which alludes to Yoko Ono back in Britain whom he had become infatuated with and his nicotine withdrawal) and when he learned that the Maharishi had apparently made unwelcome advances toward one of the women penned the bitter Sexy Sadie (“you made a fool of everyone”). It was originally titled Maharishi.

And that was the end of the Rishikesh sojourn.

They were profligate with their writing and the Esher demos on the expanded set also include songs which appeared in their subsequent solo careers: Harrison's Sour Milk Sea which he gifted to fellow Liverpudlian Jackie Lomax, McCartney's Junk appeared on his debut solo album, Lennon's Child of Nature (abandoned but the tune coming back as Jealous Guy on the Imagine album) . . .

The Echer sessions – with overdubs – offer an interesting insight and are sometimes very funny.

Lennon's Dear Prudence comes off as a much more gentle piece (until the end where he makes some acerbic comments about the subject) as does Sexy Sadie oddly enough given its subject; the short take of Harrison's While My Guitar Gently Weeps (with the additional verses) is sheer delight as an acoustic ballad; songs devolve into laughter, witticisms and asides from Lennon (check I'm So Tired).

Many songs are remarkably close to the finished versions (obviously the acoustic songs Blackbird, Julia, Mother Nature's Son, Cry Baby Cry, McCartney's still incomplete Junk) but others underwent considerable electrical embellishment in the studio late (Back in the USSR, Everybody's Got Something to Hide, Revolution).

And the stoner What's the New Mary Jane is taken rather more seriously than its content would suggest. Lennon was really pitching it as a single, or at worst as a B-side. (After all they'd delivered You Know My Name as a B-side so . . .)

Harrison's dreamily philosophical meditation on life and reincarnation in Circles (“he who speaks does not know”) is especially lovely in the Echer session but didn't make an appearance until he revisited it for his Gone Troppo solo album in '82. Not Guilty has not aged well despite his best efforts at home and in subsequent studio sessions.

Harrison's dreamily philosophical meditation on life and reincarnation in Circles (“he who speaks does not know”) is especially lovely in the Echer session but didn't make an appearance until he revisited it for his Gone Troppo solo album in '82. Not Guilty has not aged well despite his best efforts at home and in subsequent studio sessions.

Among the studio sessions is take 102 of Not Guilty . . . and even after that Harrison's perfectionism still didn't allow it to find a place on the White Album.

There is a lovely version of Good Night with the others providing something like choral harmonies.

Also in the studio sessions are takes of Lady Madonna, Across the Universe, The Inner Light, Hey Jude and Let It Be . . . none of which were on the original White Album.

The 10 minute version of Revolution becomes a weird jam from the halfway mark and Lennon's panting and screaming providing material to be sampled for Revolution 9.

The instrumental rehearsal of Everybody's Got Something to Hide is a brittle blues (Yoko's Walking on Thin Ice seemingly not far in the future); the 13 minute first version of Helter Skelter (second take, “hell for leather”) comes on slow and throbbing with Lennon on bass, and some distance from the balls-out released version (take 17 later is right there in the up-to-11 treatment) . . .

The instrumental rehearsal of Everybody's Got Something to Hide is a brittle blues (Yoko's Walking on Thin Ice seemingly not far in the future); the 13 minute first version of Helter Skelter (second take, “hell for leather”) comes on slow and throbbing with Lennon on bass, and some distance from the balls-out released version (take 17 later is right there in the up-to-11 treatment) . . .

And so it goes.

There are many insights into their working methods here: Lennon in the studio asked how fast for Sexy Sadie, his reply is, “However you like, feel it”; McCartney looking for the first note on Hey Jude; and as anyone who has seen Let It Be or heard the bootleg outtakes of those sessions knows they would often branch off into snatches from familiar old songs (St Louis Blues, You're So Square) or just jam (Blue Moon, Los Paranoias).

They certainly don't sound that demanding either: “I'll just have cheese and maybe some Marmite sandwich and coffee, okay 1-2-3 and 4,” says Harrison before immediately launching into While My Guitar Gently Weeps.

At the end of a blazing take of Helter Skelter McCartney says in thick Liverpudlian voice, "Keep that one, mark it 'fab'."

When the album came out it was widely acclaimed although not by the hard Left which was expecting the Beatles might have had something to say in that politically volatile year.

The nearest things came was Lennon's Revolution, the furious electric version of which appeared as the b-side to Hey Jude. But as with the Stones' Street Fighting Man it sounded more radical than it was. Lennon in fact said when it came to anger and destruction you could count him out . . . but for a different version on the White Album he interpolated “in” after the word out.

It was a bob-each-way from a man who felt caught in the sight-lines of the revolutionary rhetoric.

There was also McCartney's Blackbird which McCartney has taken to saying was a nod to the Black Panthers (he has Angela Davis on the back-projections at shows for this one).

But whatever perspective you take on the White Album – apolitical or not, a collection of songs by individual writers sometimes but not always with the assistance of the others, post-modern or just too long – it remains a remarkable document of creativity, personal interests and songs with backstories: Harrison's Savoy Truffle about Clapton's sweet tooth; McCartney's Martha My Dear about his sheepdog; Lennon's Cry Baby Cry prompted by an advertisement . . .

And it also included the throwaways: Why Don't We Do It In The Road?, Birthday, Honey Pie and Ob-La-Di-Ob-La-Da (an early stab at ska) alongside undiluted genius.

If you doubt it, just check Lennon's witty but withering lyrics on Glass Onion, or the stylistic pastiche that is Happiness is a Warm Gun.

And with the expanded editions you get the working drawings, the aural sketchbook of the White Album as it were.

The White Album – despite its variable quality and length -- sounds even more remarkable for its courage and careless disregard for the conventional wisdoms of rock culture.

As McCartney would later dismiss those who said it was too long: “It's great, it sold, it's the bloody Beatles' White Album. Shut up!”

Well, at the high end in the big box it is even longer: 107 tracks.

In 2010 when Rolling Stone magazine compiled their 100 Greatest Songs by the Beatles – that's about half the originals they released – there were 13 songs included from The White Album.

In 2010 when Rolling Stone magazine compiled their 100 Greatest Songs by the Beatles – that's about half the originals they released – there were 13 songs included from The White Album.

The White Album was an unusual but remarkable collection, an album very much out of step with the times, unlike all their previous releases which captured, defined or exemplified the zeitgeist.

Yet, it's quite something and less time-locked than those which had preceded it. That, ironically, gives a more enduring quality than Sgt Pepper's or Magical Mystery Tour.

And maybe in this age when people refine albums down to tracks for Spotify playlists or calculate not to challenge their audience, even more remarkable.

You can't imagine Coldplay, Radiohead, Foo Fighters or anyone else willing to put songs as diverse as Bungalow Bill, Honey Pie, Helter Skelter and Goodnight alongside Revolution 9 and Good Night all in the same album space.

It's the bloody Beatles' White Album.

The Beatles' White Album is reissued in a stereo remix by Giles Martin from the original master tapes on vinyl and CD (the double CD coming with an extra disc of the Esher demos). The four-vinyl edition is the original double and another double of the Esher demos.

There is also the Deluxe seven disc set: The original album across two discs, one of 27 Esher demos, three more discs of studio sessions and rehearsal outtakes, and a Blu-Ray with the album in 5.1 mixes, high resolution PCM stereo and the original mono mix. And the 164-page hardback book.

For further details see here.

post a comment