Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Angel Caterina (1983) demo

The notion of “the group” is firmly embedded in rock culture. From the Ronettes through REM and the Ramones to Radiohead, the concept of a small coherent unit is a cornerstone, even if in some instances – as with the Rolling Stones, Motown acts and famously Menudo – the moving parts may change.

Think the alphabet: Abba, Beatles, Clash, Doors . . .

A few artists have bucked the concept (Howe Gelb of Giant Sand has interesting things to say about it) and early among them was Jimi Hendrix.

When he was taken to London in September '66 by Chas Chandler (of the Animals) he was hooked up with bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell.

And so the group, a power trio to challenge Cream, was founded: the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

In '67 they released two albums – the seminal Are You Experienced and Axis; Bold As Love – but by '68 and less than 18 months after that debut album Hendrix was broadening his musical vision – and inviting other musicians into the studio.

Among them who worked on the songs which became the double album Electric Ladyland released in October were Jack Casady of Jefferson Airplane, Dave Mason and Stevie Winwood of Traffic, his old army pal Buddy Miles on drums (who would later be part of Band of Gypsys), Al Kooper on piano and others.

Among them who worked on the songs which became the double album Electric Ladyland released in October were Jack Casady of Jefferson Airplane, Dave Mason and Stevie Winwood of Traffic, his old army pal Buddy Miles on drums (who would later be part of Band of Gypsys), Al Kooper on piano and others.

The old order of coherence seemed to be breaking down although -- as with Clapton's guest appearance on the Beatles' White Album – these players were unacknowledged on many covers because of the usual record company politics at the time.

The album may have been credited to the Experience, but this was something more amorphous than a “band”. And Redding was in and out of the sessions.

This was a Hendrix conception which was experimental and touched on the blues, funk, politics (House Burning Down written about the riots ripping apart black neighbourhoods in the States) and more free form jams.

If that stunning debut had staked out the broad territory Hendrix (at that time) thought he might occupy, these four sides dug deeper into them and pushed the boundaries out a little further.

His democratic tendencies – or appeasement – meant there were a few duffers on the album: Little Miss Strange by Redding is an unworthy entry and Come On seems very slight within the context.

But elsewhere there was studio magic conjured up. Largely through Hendrix's perfectionism and multiple overdubs.

His version of Bob Dylan's All Along the Watchtower (on Dylan's John Wesley Harding album of the previous year) is a masterpiece of overdubs and tape manipulation. A conception which could only exist in the studio, perhaps. Although he would play it live.

His version of Bob Dylan's All Along the Watchtower (on Dylan's John Wesley Harding album of the previous year) is a masterpiece of overdubs and tape manipulation. A conception which could only exist in the studio, perhaps. Although he would play it live.

As did Dylan, but in the manner of Hendrix and not his acoustic original.

"It overwhelmed me, really,” Dylan would say some while after of the Hendrix version. “He had such talent, he could find things inside a song and vigorously develop them. He found things that other people wouldn't think of finding in there.

“He probably improved upon it by the spaces he was using. I took license with the song from his version, actually, and continue to do it to this day."

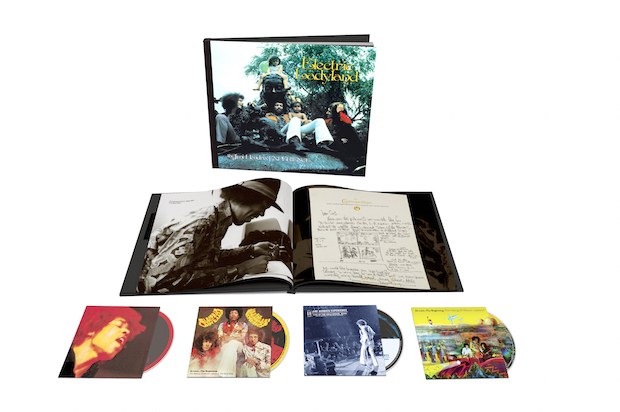

There are 50thanniversary editions of the album now released which include the album remixed by Eddie Kramer (Hendrix's longtime engineer and in charge of the Hendrix family reissues and releases) and remastered by Bernie Grundman. It also comes with a bunch of early takes, many of which are just Hendrix and his guitar in the studio or a room in the Drake Hotel in March '68 working through the songs, plus a live recording of a Hollywood Bowl show around this time (mostly of pre-Ladyland material which hadn't come out at the time but a bruising eight-minute version of Voodoo Child) and more.

Now let it be said that all this extra material (especially the live album) might be surplus to requirements for the casual Hendrix aficionado who already has his key studio albums (just the three) and a couple of live albums (of the dozens available).

But hearing him on the Making Of disc/LPs is certainly like eavesdropping . . . and he seemed very attached to Long Hot Summer Night of which there are a number of solo demo sessions and takes with Kooper on piano (and one also with drummer Mitchell).

It was a song which he maybe felt matched Dylan for its allusions and shape-shifting personae but was also very revealing in that he disliked answering the phone: “Around about this time the telephone blew its horn across the room. Scared, little Annie, clean out of her mind and I tell you. Roman the Candle, he peeps out of his peekaboo hide and seek and grabbed little Annie from the ceiling just in time . . . and the telephone keeps on screaming.”

The four minutes plus demo of the groove-riding Rainy Day Dream Away (just 4.37) established the template for one of Electric Ladyland's highlights with Freddie Smith on brusque sax and Hendrix flaming up the spaces. It's all there and would, in the studio, be distilled down a minute shorter.

But this free-flow demo is exciting for its sheer energy.

But this free-flow demo is exciting for its sheer energy.

There is also a 10 minute demo of the downplayed Voodoo Chile with just him on supporting electric guitar dialed down (and intuitively exploring blues figures he could so effortlessly channel) which again hints at its many possibilities and – if you have only heard the two finished versions on the album – you'll be somewhat in awe of how this turned out so differently.

And so differently . . . twice.

Jimi-spotters will enjoy the easy-rollin' blues My Friend and will recognise where it went subsequently. And the outtake of Redding's Little Miss Strange without Hendrix but Redding on guitar (his first instrument) drummer Buddy Miles and Stephen Stills on bass is a sharp little workout.

Elsewhere there are snatches of songs he would return to frequently: Angel, Cherokee Mist and Hear My Train A Comin'.

And on versions of 1983 . . . (A Merman I Should Turn To Be) he sings with gentle sensitivity.

Engineer Eddie Kramer and this album's co-producer John McDermott attest to how Hendrix used the studio: “Noel appreciated Chaz (Chandler)'s taskmaster approach, which Mitch used to joke about all the time,” McDermott told Rock Cellar recently. “[Chandler] was like, 'You don't need to spend all this time'. And for Noel he didn't have the interest in recording that Jimi did.

Engineer Eddie Kramer and this album's co-producer John McDermott attest to how Hendrix used the studio: “Noel appreciated Chaz (Chandler)'s taskmaster approach, which Mitch used to joke about all the time,” McDermott told Rock Cellar recently. “[Chandler] was like, 'You don't need to spend all this time'. And for Noel he didn't have the interest in recording that Jimi did.

“Jimi used the studio to write and create.”

But Kramer also noted that “Jimi was very good at discipline”.

“Think about how he grew up. His dad was pretty tough with him, goes to the army, goes to the chitlin' circuit. I couldn't imagine more discipline.

“And here he is in the studio, he knows what needs to happen. How does it work?

“He knows the process and would encourage us to push the boundaries. So as a producer he knew precisely what he wanted. He had the sound in his head. He had the direction of the artwork.

“He knows the process and would encourage us to push the boundaries. So as a producer he knew precisely what he wanted. He had the sound in his head. He had the direction of the artwork.

“Everything was his concept.”

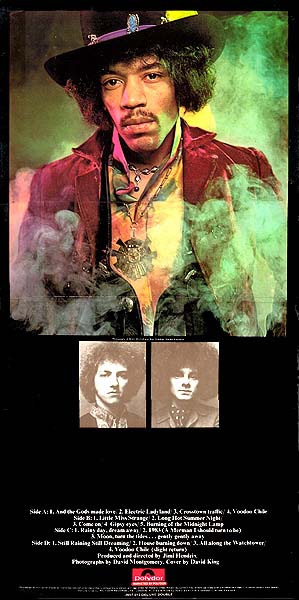

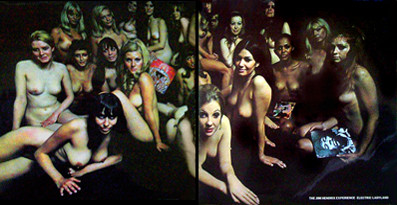

Which explains why he was so angry with the cover which featured naked women.

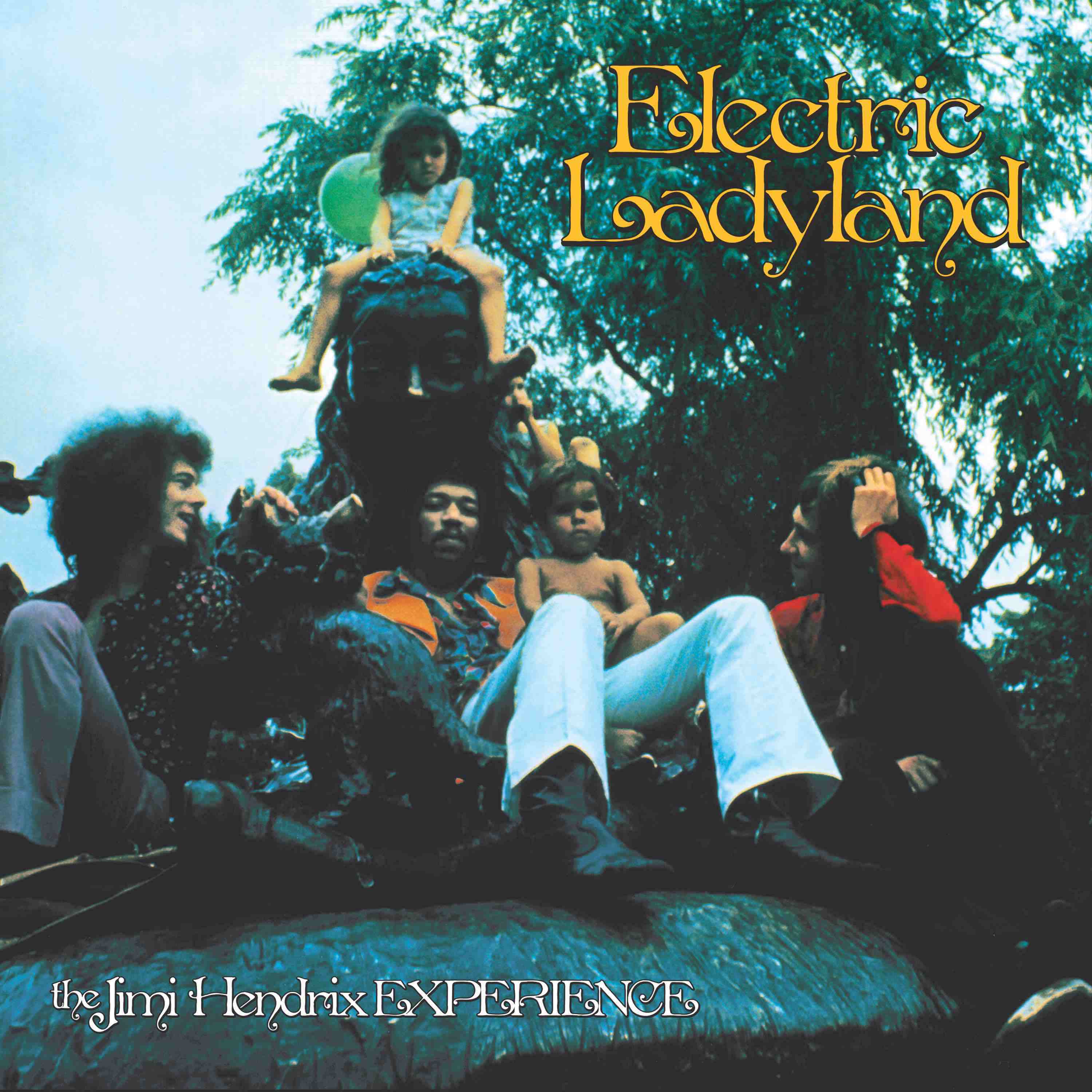

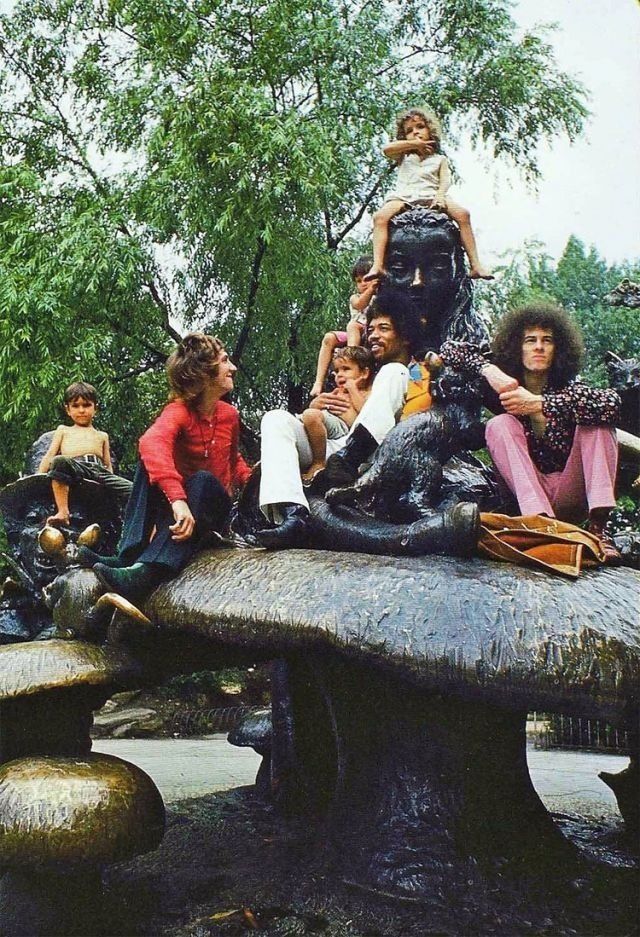

His choice was a photo taken by Linda Eastman of the trio with children on the stature of Alice in Wonderland in New York's Central Park.

His choice was a photo taken by Linda Eastman of the trio with children on the stature of Alice in Wonderland in New York's Central Park.

That cover – relegated to the inner sleeve

previously – has now been restored to the reissue.In other territories it had different covers again: a cheap fuzzy live shot in the US, in New Zealand his striking portrait from the back cover used on the front and in Europe there were different ones again.

Now with the proper images in place, the remixing (which also includes a fourth BluRay disc with original two-track stereo mixes, the 5.1 surround sound sonic experience and a DVD doco of interviews) and the additional studio and live material Electric Ladyland (long an Essential Elsewhere album) gets re-presented in its enhanced glory.

You'd like to think that a seminal rock album like Electric Ladyland reset the co-ordinates, dismissed the limiting concept of A Group in favour of the creative collective exchange of ideas by like-minded and empathetic musicians which would get Jimi and Miles in the same studio and . . .

Didn't really happen, did it?

Which may be why Electric Ladyland – however you hear it, in its original incarnation or in these expanded iterations which come with a 48-page hardback of rare photos and Hendrix's handwritten lyrics and notes – seems like an aberration, a ripple in the rock cosmos, a moment when the impossible seemed within the grasp and . . .

That was then and this is now.

Plus ca change . . .

Graham Hooper - Nov 27, 2018

I had the Original New Zealand Cover with the Naked Ladies ..That is The Electric Ladyland Album I Remember not the Re Issue with Live Image of Jimi...

Savepost a comment