Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Many obits are easy because most of the subjects are of great age and haven't done anything much in recent decades.

But then they look at their words on Bob Dylan.

A decade ago when he was approaching 70 they might have been prepared to put a full stop on their work and his career.

But since then he has released an acclaimed album of original work (Tempest in 2010), three albums of covers (one a triple), has touring art exhibitions, launched his own whisky, made sculpture, been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature (the first for a songwriter) . . .

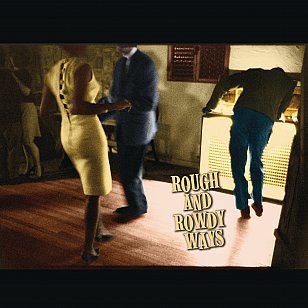

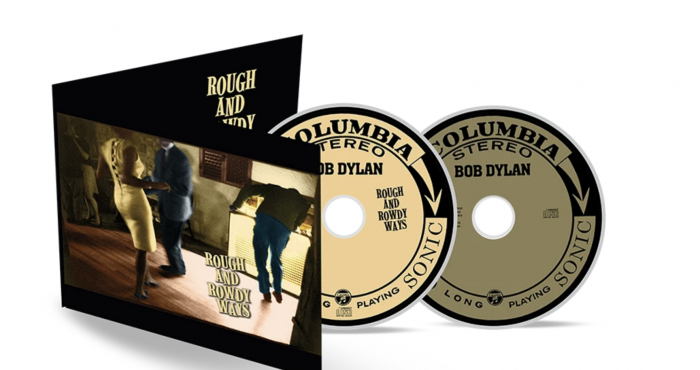

And now a new double vinyl album Rough and Rowdy Ways (Sony), telegraphed by the surprise release of his 17 minute Murder Most Foul, the equally extraordinary I Contain Multitudes and the vaguely semi-autobiographical and misdirections of False Prophet.

Has Dylan ever released three songs in advance of a new album?

Has Dylan ever released three songs in advance of a new album?

Not that I can see, but then he's also the man who unwittingly launched the bootleg industry, box sets (with Biograph) and the whole idea of an archive trawl with his Bootleg Series.

If the obituary writers were thinking Dylan was a done deal a decade ago, they now have their work cut out again because Rough and Rowdy Ways is one of the most exceptional, lyrical and metaphorical in his vast catalogue (it is his 39th studio album in 58 years of recording) and offers an encompassing view of life, history, personal allusions and much more which reach from Ginsberg, Corso and Kerouac to Elvis, from the ancient muses to John F Kennedy, from bluesman Jimmy Reed to Walt Whitman, from . . .

Anywhere there to anywhere here, in fact.

This is the intertextuality which ex-pat Kiwi classics professor Richard F Thomas of Harvard wrote of in Why Bob Dylan Matters four years ago, in which he spoke of Dylan's “new mode of songwriting that has given his work a more conscious allusive and literary focus”.

Dylan has always borrowed – initially from old folk and blues songs – but in the past couple of decades his references (through lines or characters) have become more inclusive and, as he said himself, “quotation is a rich and enriching tradition”.

And so it proves right across Rough and Rowdy Ways, an album of songs to decode and deconstruct, and sometimes to be lead down blind alleys or in circles.

It is a masterpiece of references and co-existing realities, like a Chagall painting or a Giotto mural where events and people from different places and times occupy the same space.

The album opens with I Contain Multitudes (which we considered at length here) and it stands as an emblem of both what follows and about Dylan's artistic life.

It's always a folly to believe the “I” in any lyric is the songwriter (Dylan didn't marry Isis on the fifth day of May) and here he is most often the universal narrator roaming through time and space, from the Bible and ancient mythologies, through outlaws and heroes to the murder of John F Kennedy (on Murder Most Foul) to the Beatles and Stones and beyond.

Equally Dylan here – as he has done before (John Wesley Harding, Joey etc) – uses characters as cyphers rather than for them to be interpreted literally. He invokes (“Scarface Pacino and the godfather Brando, mix it up in a tank get a robot commando”) and they evoke images and ideas in the listener.

And the album ends with the majestic Murder Most Foul (considered previously here) which takes out the whole of the final side of vinyl.

Between those points he adopts the sound of Muddy Waters for the typically cryptic and mythic False Prophet (“I ain’t no false prophet, I just said what I said . . . I’m nobody’s bride, Can’t remember when I was born and I forgot when I died”), explores low blues (My Own Version of You) and Mother of Muses has a folk-gospel framework with a reference to nymphs of the forest before a consideration of heroes who stood alone (Sherman, Patton among them) and how they cleared the way for those who followed (Presley, Martin Luther King).

“Man I could tell their stories all day.”

And musically – as on Goodbye Jimmy Reed where he reaches to Leopardskin Pillbox Hat – he touches his own history.

Perhaps the seven and half minute, John Lee Hooker-style blues of Crossing the Rubicon gets somewhere close to the personal. But as always it is unwise to read too much of Dylan into Bob Dylan's songs.

Perhaps the seven and half minute, John Lee Hooker-style blues of Crossing the Rubicon gets somewhere close to the personal. But as always it is unwise to read too much of Dylan into Bob Dylan's songs.

It's best just to immerse yourself in the electrically charged imagery, the misdirections and sleights of hand and come out the other end with some overall impression where details are less important than the suggested picture.

Dylan here doesn't address directly these difficult days of uncertainty, rage and division but rather explores the images which come when reason sleeps and waking dreams where disparate images and memories come into the same space.

In lines as hard, clear but as allusive as TS Eliot yet as intellectually dense as Ezra Pound, he builds up refractions and reflections from a wide swathe of human and personal thought. History implodes.

In lines as hard, clear but as allusive as TS Eliot yet as intellectually dense as Ezra Pound, he builds up refractions and reflections from a wide swathe of human and personal thought. History implodes.

Without doing so specifically, we may be reminded that the younger Goya who delivered poised society portraits was also the same Goya who later painted the interior walls of his home with the nightmare visions of The Black Paintings.

The Dylan who seduced with Lay Lady Lay is also the same Dylan who sang of the killing of Emmett Till and here lays out a murder most foul.

Goya and Dylan – and you, and me – contain multitudes.

There is some cynicism here (notably on Murder Most Foul) but also a softness too.

His recent albums of covers have smoothed some edges off his voice as heard on the ballads I've Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You (“If I had the wings of a snow-white dove, I'd preach the gospel, the gospel of love . . I hope that the gods go easy with me”) and the dreamy Key West (Philosopher Pirate) where he sings “death is on the wall . . .”

He has been down this meditation before of course, and as the-then 61-year old Tom Waits once told this writer, if you aren't thinking about death “then you aren't paying attention, are you?”.

Yet mortality is everywhere here from the opening lines of I Contain Multitudes (although so is life) and memory – collective, learned or lived – imbues everything.

“I've already outlived my life by far,” he sings on Mother of Muses.

Or try the suspension of time – and the timelessness – on Black Rider.

If this is 79-year old Bob Dylan's final album then it is majestic, sometimes bewildering, occasionally invoking a pessimism borne of experience . . . but always engaging and intellectually dense.

And with strong tunes grounded in the American traditions he has explored.

But pity those obituary writers because while they are dealing with this extraordinary collection and its intimations of mortality in the back of their minds will be those earlier words by Bob Dylan: “It’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there . . .”

And he wrote those 23 years ago.

Rough and Rowdy Ways in on Spotify here and will be available on double vinyl on July 17.

Rough and Rowdy Ways in on Spotify here and will be available on double vinyl on July 17.

JB Hi-FI have a limited number of copies of the double album on gold vinyl available for pre-order on their website here.

.

There is much more about all aspects of Bob Dylan's career at Elsewhere starting here.

GlimmerTwin - Jun 22, 2020

You can't help but shake your head yet again as to how he conjures up word associations, narrative , stories etc. Then there is always the music, which in this case seems to have more variation and subtlety since the Love & Theft album. When there is a derivative stomp like Goodbye Jimmy Reed the groove is infectious and swings - I'm reminded of the Stones then you realise he has been playing with the core group for many years now (Charlie Sexton, Tony Garnier etc) and have created a unique sound. Yes this is that good, play on brother Bob and do a Major Tom and hit 100.

Savepost a comment