Graham Reid | | 3 min read

There was a scene in Michael Palin’s much acclaimed travel-doco Himalaya which, even if you didn't see it, you'll recognise. It was of a towering mountain with clouds scuttling over at about 10 times the speed. Such an image is over-familiar these days -- you see it often in ads which indicates how cliched it has become -- but the accompanying music caught my attention. It was a series of repeated and slightly varying phrases known as minimalism.

"Koyaanisqatsi," I yelled to the bewilderment of those around me. But that's what it was. Palin's team had appropriated not only the sped-up image, but added similar music to Godfrey Reggio's '83 film Koyaanisqatsi (Life out of Balance), which was a whole movie using this (and other once innovative) filming techniques -- and Philip Glass' minimalist music.

I remembered it as an exceptional film, and because it is on midprice DVD I bought it and we sat down to watch. We didn't move, and barely spoke, for the next 90 minutes.

It's still an impressive work and if the music isn't to your taste you can turn it off, bang on Strauss or the Clash, and still remain engrossed by the visuals. However, many of them -- clouds racing over landscapes, cars zipping along freeways -- have become overly-familiar these past two decades, although the impact has seldom been bettered than in Koyaanisqatsi.

For Palin's crew it was the easy but eye-engaging option: just add minimalism.

Many film-makers determine how we see the world.

John Ford defined the West for audiences when he shot great films like The Searchers in Monument Valley, Arizona. (In The Searchers he identified it as Texas but no one cared, it was just the uncharted but visually impressive land known as the West).

Two decades later Sergio Leone redefined the West in movies like The Good, The Bad and The Ugly as an unforgiving wasteland of bleached deserts, low brush and rock. They were actually shot in Spain, but when Clint Eastwood walked through them to the sound of Ennio Morricone's haunting music it became the West. Another imagined West!

Some directors define emotional landscapes: Martin Scorsese set the template for contemporary New York gangster movies with Mean Streets and created a violent masterpiece (with a great pop'n'rock soundtrack) in Goodfellas.

Films like Brian DePalma's Scarface and Scorsese's Casino (set in Miami and Las Vegas respectively) are just variants of the same emotional and physical environment.

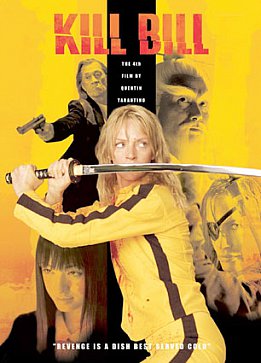

Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill films also illustrate how much he has defined his own filmic landscape by drawing from all that went before.

Kill Bill (notably the second volume of the two) adopts not only the soundtracks of its predecessors (he uses snippets from Morricone's Good, Bad and Ugly, oddball but distinctive Spanish music of the El Mariachi kind and so on) but even appropriates whole chunks of visual style.

When the Bride (Uma Thurman) goes to learn from her kung fu master, the sequence (from grainy and bleached film to sudden zooms and mystical sayings) comes from cheap '60s Asian martial arts movies.

Also, Tarantino uses manga (comic-book art), direct-to-camera commentary, voice-overs and shifts to black and white. Like Natural Born Killers (or Spielberg‘s rather more lowkey but still striking Duel), it's a homework assignment for film students: count the long shots, look for framing devices, ask yourself why the low angle etc.

This is not a unique observation of this much studied and perhaps over-acclaimed director, but Kill Bill reminds you just how much Tarantino defined a style of often archly referential movie-making.

Over the two volumes Kill Bill is way too long and ultimately self-indulgent. By the final showdown, which involves absurd globs of dialogue in which Tarantino's voice is unashamedly filtered through Bill (David Carradine), you just want one of the Weinstein producers to wander on and cry, "Enough already".

But what you can admire after the buckets of blood, the limbs hacked, the balletic fights and constant shifts of colour and tone, is how Tarantino has managed to create an emotional landscape of his own, albeit a pastiche of ideas from others.

Spike Lee (another who has staked a territory) doesn’t rate Tarantino at all. His great quote was “I don’t need a guy named Queeeeentin to tell me about movies”.

But like him or not, Tarantino is the archetypal postmodern film-maker, every image or style worth as much as any other. And he's become an adjective. Just as you might speak of an epic western being Ford-like, or snort "Koyaanisqatsi" during an insurance company ad, you can also say, "That's sooo Tarantino."

Or, if you want the derogatory tone of a Spike Lee, as you might in the final 20 minutes of Kill Bill: "That's so Queeeeentin."

post a comment