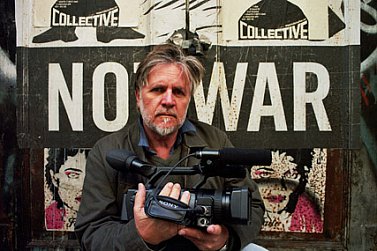

Graham Reid | | 10 min read

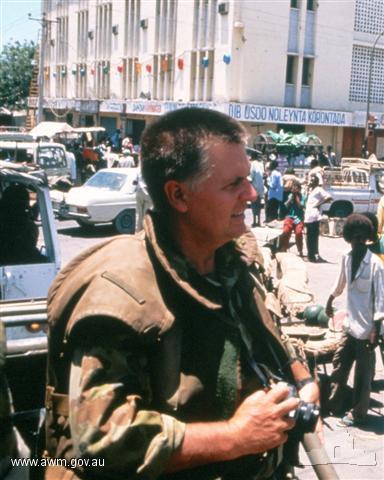

Australian documentary filmmaker and painter George Gittoes is used to being in war zones, he’s covered every major conflict -- usually uninvited by the warring factions -- since Vietnam: the depressingly long list includes Rwanda where he witnessed and filmed the Kibeho massacre in 95 where as many as 8000 may have been killed, Somalia, Bosnia, Nicaragua, Gaza, Cambodia, Afghanistan, Iraq four times . . .

And most recently the streets known as Brown Sub in Liberty City, Miami. This is a part of Florida where no sane tourist would venture.

“It’s like being in Mogadishu or Baghdad,” says 57-year old Gittoes, who would know. “It was a war zone. I don’t like to put statistics into my films, they are often boring. But the stats in Liberty City are that one in nine men don’t make it to 21 because they have been killed in violent incident. Those are worse stats than for American soldiers in Iraq.”

It was his film on Iraq -- Soundtrack to War -- which took him to these streets where gang-bangers and drug dealers live to the hard rhythms of hip-hop and every kid is an aspiring rap star.

As one who has music in his blood -- his grandmothers were both pianists, one grandfather a violinist and the other sang tenor, his dad sang Bing Crosby-style and he himself always played -- Gittoes has always considered music the third element in film.

Soundtrack to War focuses on American soldiers in Iraq and the music -- from thrash metal to rap and gospel -- which keeps them going, and which they spontaneously make while on a break.

While filming, Gittoes befriended a number of these soldiers, including Elliot Lovett from the mean streets of Miami. Lovett told him of his family and his younger brother Marcus who he insisted was a gifted poet-rapper.

Gittoes followed his instincts and made the trip to Miami with the intention of creating a Stateside sequel to Soundtrack to War which focused on music in a similarly dangerous place.

The result, Rampage, is more than that however: it is a rare journey into the ghetto to encounter a loving family which is intelligent -- “the boys all have IQs off the scale” -- but trapped in a culture which belongs to drug dealers. Children as young as three toy with guns, walls are pockmarked with bullets from AK47s, and kids spit rhymes about killing and revenge. It is a compelling -- and tragic -- film which thumps to an urgent soundtrack of rap.

“I regard Rampage as a documentary opera, a rap opera,” says Gittoes. “I would record live raps as they happened without being intrusive and when the DVD comes out it will have a CD of a lot of the live raps with it.”

Gittoes says he had access denied to others because of the success of Soundtrack to War which had been screened on VH1 -- the free-to-air music channel -- and Elliot had become something of a local star in the hood.

Gittoes is also an Australian not a white American, he knows the music business intimately (Eminem’s producer among many others) so was respected for that, and he was familiar with danger zones. He was trusted, and also trusted them.

“Willy T the drug dealer showed my 18-year old son how to make crack cocaine, and often they’d stick guns in the back of my belt if they thought they were about to be frisked.

“If I’d been picked up with Willy T and these guys with their drugs and guns in my car I would be in a Florida jail today, it was a risky business. But it’s about trusting them in their world.”

Gittoes says much as he enjoyed the film Blood Diamond he says the journalist in it -- played by Jennifer Connolly -- applies her own moral code to the world she is in and criticises the ethics of people around her.

“A real journalist working in a war zone like Miami does the opposite of that. Being non-judgemental is how you get real access.

“I’m very relaxed where I am and I don’t have one foot out the door, I don’t have a meter ticking. I’m there for them and I include people in the project. Rampage was in a sense made easy because everyone in the hood had watched Soundtrack to War because Elliot was in it.

“So I came in as the guy who had broken down this infinitely high wall which never lets any of their stuff out. They are all creating this wonderful material but it never gets heard, they don’t even have the resources to release mix tapes.

“They all saw me as the guy who could spotlight them as well. I’d done Elliot and they could become like the soldiers in Soundtrack to War. A lot of people there compared it to American Idol and that they now had their chance. They knew that I wasn’t this guy with an amateur camera, I was for real and was someone who could get them mainstream attention.”

He laughs that even drug dealer Willy T saw his chance to become a star through this film.

“I was out filming a drug deal going down and a guy came after me with a gun. So I ducked into a door, and Willy T was there. He was the boss of the guy with the gun and I’d gone into this spider’s nest, but quickly I could authenticated myself as a music guy -- and Willy T had ambitions and wanted to be 50 Cent.

“Grandma thought I was the FBI, but Willy T thought it would be a pretty elaborate ruse for an FBI guy to have made these films and know people in the music industry.“

But it is Elliot’s 20-year old brother Marcus -- the only one in the Lovett family involved with drug dealing -- who is central to the story. He is undoubtedly talented and Gittoes thought to get him to a recording studio in Atlanta where he had contacts - but then it all goes wrong.

“I would be recording their raps but at the time wasn’t listening to the lyrics. It was only when I edited that I realised the tension was building. Marcus says in one, ‘my mind is gone, I’m already dead’ and I think he realised he was in danger.

“Marcus was an impressive individual. I’ve been on hundreds of patrols in Somalia, Afghanistan, Somalia and God knows where with a really good lieutenant or corporal. With them you get this sense that even though they are younger than you, you are completely under their charge.

“So if I was with Marcus and he said, ’Put the camera down, we’ve got to take cover’ I’d do exactly what he said. He had a military section, and a pretty well armed one.

“He seemed to be in command . . . but when I look at my rushes I can see Marcus was losing it.”

While Gittoes was in Atlanta Marcus was killed by a 16-year old hitman for a gang.

“The people who killed him were the Homo Thugs, infinitely more experienced, 35-year old guys who’d never regard themselves as homosexuals but had been [having sex] with men in jail and then they were [having sex] with young boys when they got out.

“The boy who killed Marcus worked for them.

“They were just better organised. I didn’t know that was the gang Marcus was challenging. If I had known, I would have sat down with him and said, ’Marcus, you’re mad. You are maybe eight or nine guys and they have a hundred or more.”

Gittoes says African-Americans will read Rampage in a different way to how a white audience will see it: they know that in the ghetto their worst enemy is themselves; pretty girls get their faces cut, and kids who try hard in school get their fingers broken.

“There is a chance that word was out -- exaggerated I have to say -- that Marcus was going to record and there was jealousy that he was going to have a break, so the gangsters ordered the hit on him.

“But it was also a turf war. The Lovett family had been there for 14 years but the drug dealers took over where they lived. Marcus and his friends decided because they lived there it was their territory.

“I’ve never had anyone close to me killed before. I‘ve seen a helluva lot of death, particularly in Rwanda, but I came to think I was immune and the people around me were somehow or other always going to be okay. This is the first time I have had someone close to me, someone in something I was filming, be killed.”

After Marcus’ death Rampage becomes an almost completely separate film as it follows the surviving Lovett family and younger brother Denzell on his journey through the insidious world of the recording industry as he too tries to make it as a rapper.

Everyone at the top of many record companies says he is gifted, but no one wants to hear violent, gun culture rap from a 14-year old. The irony is that the rap world wants to be real, but Denzell’s world and rhymes are too authentic, and unmarketable.

“Regardless of those [record company] guys being duplicitous, no one anywhere has said anything other than Denzell being a star, that’s been universal.

“We will get his CD out, we are working on him maybe having his own label now.

“But all this costs us a huge amount of money, way out of the dimensions of what we can make from the film.”

As an insight into a dark world baking under the bright sun of Miami, Rampage is a remarkable document and one which may change audience perceptions.

“Willy T is like a good businessman anywhere in the world. In that community selling drugs is one of the very few forms of empowerment where you can actually run a business and get money that is not a handout.

“In our society it’s a bad thing to be a drug dealer, in their world it’s a step up. It’s about respect, you can buy a car with you own money and you don’t have to walk everywhere. I have a lot of respect for Willy T. You realise the difference between the bad drug dealers and the good ones. The guys who killed Marcus are like Idi Amin, just terrorising people all the time.

“But Willy T’s gang wouldn’t use hard drugs, they were intelligent, and sitting with them was like being at a Middle East coffee table discussing politics. They are smart and loved discussing politics. And they do policing, and jobs that social welfare organisations should be doing.

“It’s hard to turn your head from the fact they are selling drugs, but they do have a sort of morality that you have to accept.”

Gittoes says the Lovett family -- like most people he has featured in his docos they remain close friends and are now part of his extended family -- were moved to another area of Liberty City after the filming, but just recently their house was strafed by bullets and their car crushed by baseball bats and bricks.

The Homo Thugs had found them. The code of the street says the Thugs are worried that one of the brothers will come after them so it is better to take them out first.

“Elliot is out of army now and back in Miami. But the pressure on him and his younger brother Alton to fight these guys is enormous. Elliot has had the white feather as the guy whose had the brother killed and hasn’t done anything.

“But Elliot -- and he could do it -- is sensible. He’d be like one guy in bad movie going up against all these guys. Alton is selfless and level-headed, he could become an Obama.”

But now as a result of the attack the family is split up.

Gittoes is still doing what he can: he will perhaps have 18-year old Alton join his film company, his wife spent two months in Miami and got the mother Teresa into a job, and he is still intending to get Denzell’s album released.

“I’m not a detached film-maker who never has contact with the subject afterwards. I regard all the people I work with as family. But this family are now living as refugees in relatives’ houses.

“It is worse than Baghdad there. Anyone seen with me in Baghdad could get killed by the death squads there too, but do you want people to stop reporting on Baghdad?

“That’s true for all journalists, but I have a small shadow unlike a CNN journalist. The people who work for Time and CNN in Iraq now file their stories from home and try to make it seem they were there.”

But very few file from Liberty City?

“African-American make films about these things which are so encoded they are like another American. White Americans would not be allowed to make a film like this, nor would a middle-class black. They hate middle-class blacks more than they hate whites. It’s very deep.

“My great-grandfather -- a George Gittoes like me -- had kids who colonised Australia but then he had another wife in Jamaica who was black. The Gittoes branch in America is black and the one in Australia is white, but there is a real blood connection and we have been friends all these years.

“All my films are very marketable because they are made in places where it is hard to get to, like Afghanistan or Iraq. But anyone can pick up a little camera and shoot a rap film in ghetto in America.

“So Rampage had to have a different quality to it. The back story of Elliot in Iraq was important, and the Australia connection was important because I was seeing it through different eyes.”

But more than a documentary maker who goes where few others dare, he is also a witness to the inhumanity in the world.

“I hate war," Gittoes told Time magazine last month. "I'm married, have a lovely wife and two kids, and I'm someone who loves classical music, poetry and literature. [But] if humanity's going to go on doing war, then there has to be evidence somewhere that someone felt something."

Footnote: George Gittoes is also a painter whose works have been entered in the Archibald Prize in Australia in 1994, 1995 and 1997. He himself was the subject of an Archibald portrait in 1998. Footage from Soundtrack to War appeared in Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11.

A much abbreviated version of this interview appeared in the New Zealand Herald in early 2007. www.nzherald.co.nz

post a comment