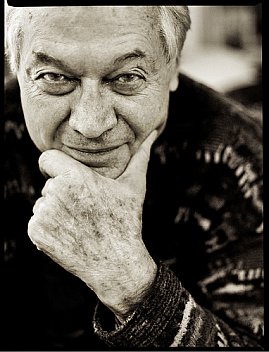

Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Roger Corman is the King of the B Grade Movie. He has directed and/or produced hundreds of films, claims he shot his cult classic Little Shop of Horrors (1960) in two days and one night, and usually brought in a movie in less than 10 days. He would often shoot sequences for two films simultaneously to save on costs and actors would also work in the crew. Because his movies were done so cheaply he rarely lost a dollar.

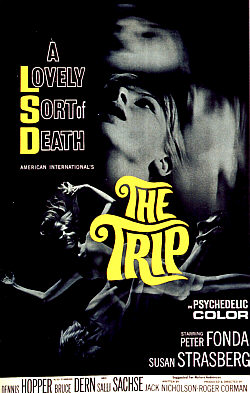

His biker and counter-culture exploitation flicks of the 60s -- notably The Wild Angels, The Trip, Gas-s-s-s -- are cult classics, he defined a kind of topless horror and action genre, but he also made a series of fine Edgar Allen Poe adaptations (with Vincent Price). His most notable flop was The Intruder, a 1962 drama about a Northern racist in the South (William Shatner’s finest screen moment).

His ability to spot talent is legendary: he was instrumental in the early careers of Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Jack Nicholson, Bruce Dern, Diane Ladd, Tim Burton, Jonathan Demme, James Cameron, Robert De Niro and Dennis Hopper.

Without Corman there would be no Easy Rider, no cheap sci-fi flicks or women-in-prison teasers, and in America probably nothing to screen in drive-ins during the 60s.

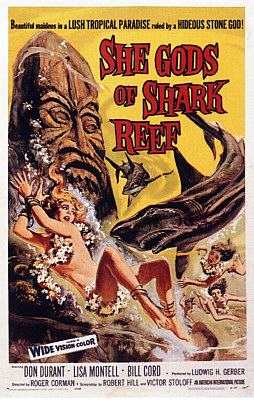

His film credits include Swamp Women, Attack of the Crab Monsters, Attack of the Giant Leeches, Teenage Cave Man, She Gods of Shark Reef, The Wasp Woman, Night of the Cobra Women, Death Race 2000, Humanoids from the Deep . . . You get the idea.

Corman is well-spoken, droll and articulate, and he still steers half a dozen movies year, usually in the genres he defined. His biggest recent success was DinoCroc, and you can guess what that was about. He is 79.

What are you doing at the moment?

I’m preparing a picture for the sci-fi channel in the United States called Cyclops, about the Greek one-eyed monster. We are also preparing DinoCroc 2: DinoCroc Versus the Volcano.

I understand there is Death Race 3000 with Tom Cruise.

Yes, I sold the remake rights [of Death Race 2000] to Tom and he is developing the script now. He’ll star in it and I’ll go along as executive producer but I believe it is more of a titular name because he is calling the shots.

The films you have been executive producer on in the last few years all seem to be in the genres you defined. Do young directors come to you with a project and are you hands on?

I’m hands on at the beginning. I believe the producer’s job is in pre-production and post-production. During the actual production I leave it primarily to the director and the production manager. I’m there to be consulted but I prefer to stay in the background. Generally I’ll come up with an idea like DinoCroc and will work with a writer to develop the script and bring in the director on the last draft when the script is in what I consider a shootable condition. We very seldom re-shoot, I don’t think we’ve ever re-shot more than one day on any picture, and on 75 per cent there is no re-shooting.

The way we work is not that dissimilar to the way Hollywood works in general. We give the director the editor with the first cut and nobody has anything to do with that. Then we have a series of cuts in which I have some people on my staff look at the first cut with the director and editor, and give them their notes. But, and this is crucial to the way we work, we never say you must make this cut or this change. We do say you must consider it but it is their discretion.

I generally come in on the third cut and it’s matter of notes going back and forth. Very seldom do we insist on a cut, because people work in good faith and you all know what needs to be done.

You have redefined the role of producer as an auteur.

I think so. Auteur to the extent that the idea of making the film, the initial concept, together with the style, the theme and the budget comes from the producer. The director then interprets that, during the shooting it is the directors thing totally.

You got into production out of sheer frustration that studios were making cuts to movies like Gas-s-s-s.

That was cut very heavily. Writer George Armitage and I had God in the picture played with an outrageous Jewish accent, but the distribution company cut God out. It may well be that we were in bad taste, but we thought it was funny. But the cuts left a lot of holes in the movie. Mel [Brooks] could have gotten away with it.

A lot of your films in the 60s were about counterculture outsiders like bikers and hippies. Did you have an affinity with them because you were an outsider yourself in Hollywood?

I think so, because I’ve primarily worked independently, although I have worked with big studios. But you give up a lot of your authority and decision-making. Some directors can do that, but I had difficulty with it so preferred to work independently. There’s something psychologically within me that is to a certain extent an outsider.

The speed at which you shot allowed you to capture the zeitgeist. Most big production lag years behind social change, and especially in the 60s social change was happening very quickly.

Yes, those were the last days of my youth. Someone said I was the elder statesmen of youth rebellion.

And you would have been only in your late Thirties at the time?

Yes, I was.

I won’t ask you about your drug intake, but if you want to tell me you may.

For The Trip I took LSD once. I smoked marijuana as most people did during that time. I’d never taken LSD but felt conscientiously I should take it once in order to find out what it was I was doing. The problem was I had a wonderful trip, but didn’t want to have the picture to be totally pro-LSD. That was another picture that was cut by the distributor as well. The actual ending was cut off, and that inspired me to start my company New World.

For The Trip I took LSD once. I smoked marijuana as most people did during that time. I’d never taken LSD but felt conscientiously I should take it once in order to find out what it was I was doing. The problem was I had a wonderful trip, but didn’t want to have the picture to be totally pro-LSD. That was another picture that was cut by the distributor as well. The actual ending was cut off, and that inspired me to start my company New World.

Do you find it ironic that what was once called gutter trash or B-movies is now widely accepted -- and as even being accepted at this time?

Yes. Times change and what was unacceptable is now acceptable.

You are referred to as the King of B Movies, is that slightly derogatory, because some of your films had a serious subtext -- The Intruder is a fine film -- and you often gave women strong roles?

The title only partially describes what I have done, however you can’t control the way public sees your work or the way the media represents it. It’s not really so terrible, so I go along with.

By it people mean low-budget films and tits’n’arse movies?

WelI, I made the films so I stand behind them.

The Edgar Allen Poe series, what drew you to his stories?

To a large extent the undercurrents and psychology of them. I think Poe -- a few years ahead of Freud who was working in a quasi-scientific way and Poe in an artful way -- was exploring a new concept of the unconscious. So I interpreted Poe from the Freudian theory I was studying. That might sound a little pretentious, they were exciting horror stories also.

We are talking academically here, but your films are very funny. Were they received that way in the mid 60s?

I’ve always felt films should have humour, particularly after The Intruder which got wonderful reviews and won a number minor film festivals -- and was the first film I ever made that lost money. I analysed why that was, and it came down to not having humour in it.

Piranha and films like that are basically absurd, you must be laughing when you are sketching them out.

We take the work very seriously but we take the creative process with a certain amount of humour.. For instance when I got the idea for DinoCroc I thought the title was funny, but at the same time that is what the film is about.

And you come up with titles before the film sometimes?

Occasionally.

An abridged version of this interview first appeared in the New Zealand Herald in late 2006. www.nzherald.co.nz

post a comment