Graham Reid | | 4 min read

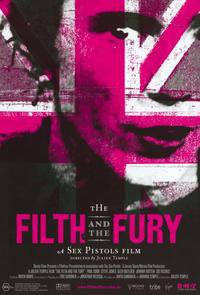

Sex Pistols: Anarchy in the UK

The Sex Pistols changed many lives, aspiring filmmaker Julien Temple’s more than most. After accidentally meeting them in their dockland rehearsal room one afternoon in 1975, he followed them as they became the most reviled band in Britain.

He filmed their shambolic, thrilling live shows, sat junkie-punk Sid Vicious down for a rare coherent interview, was assaulted in the street for being associated with them, and even now the band looms large in his life with his new documentary feature about the group and its times, The Filth and the Fury.

After the skyrocket career of the Pistols exploded, Temple made the hilarious Rock’n’Roll Swindle movie with the band’s manager Malcolm McLaren. It was McLaren’s version of media manipulation. It was also largely lies and exaggeration, and Temple says his latest Pistols documentary — which draws on hundreds of hours of band footage, interviews, clips of musicians and television advertisements from the period — is the necessary corrective to Swindle’s cartoon portrayal of life on the frontline of social chaos and four-chord truths.

“There has been a lot of theorising and philosophising about the Sex Pistols,” says Temple, “but the missing piece was always the voice of the band. I’ve tried to make this a human story rather than a theoretical one.

“Swindle was written as a deliberate polemic thrown into the ring when the band split up. It was designed to provoke and confuse the kind of idolising fans the group had attracted.

“What the Sex Pistols hoped to do was break down that idol-worshipping relationship and encourage people to express themselves rather than living through star figures.

“The attempt with Swindle was to confuse reality and fiction, but over the years those ideas have perhaps been taken too literally. This film is to partly correct them.”

Where The Filth and the Fury scores over its predecessor is in the period footage: the flop-haired pop of the day they were up against, the broader context of London’s rubbish strike and IRA bombings and the mundanity of life on the dole ...

“You can’t understand that group without understanding where they came from,” says Temple. “They were very much shaped by their time and class background. They were defined by what they wouldn’t be able to achieve and how narrow their options were. Their anger and desperation came out of that and fuelled the music.”

But that anger, in retrospect more focused than it seemed at the time, made them the scourge of Britain, especially after Bill Grundy’s television interview (see here). Through stop-frame replay and commentary by the band, The Filth and the Fury shows how provoked (and initially well mannered) they were before it descended into schoolyard slanging.

In that moment everything changed. There was a bandwagon for politicians to leap on, the Pistols became convenient scapegoats and they were assaulted in the streets. What was malcontent underground rock’n’roll noise became characterised as a social revolution to be exterminated.

“There was a moment when it almost seemed like a coordinated hunting down of them if they went out of doors. That seemed sinister.

“But when councillors were saying they were better off dead that was part of the game, it was a victory for the Sex Pistols. You knew they were shaking them if authority figures looked at kids like that. That response was expected, what wasn’t was serious violence on the street. And MI5 blacklistings.”

Temple, by association, was a target too. Walking down Oxford St reading NME, a fist came slamming through the pages.

After the Grundy show, however, the band also realised the power they had and manufactured outrage. Temple recalls them being paid to smash up a hotel lobby while photographers flashed away.

“It was a combination of having fun with it and riding the monster and also the monster fighting back and in the end reestablishing some kind of control.”

Temple’s film probes all this through

period footage but also interviews with the remaining band members today.

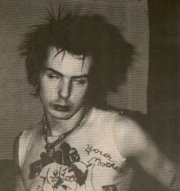

Vicious comes off remarkably well in a long intercut interview. He is a person

again rather than the T-shirt icon he has become.

As expected, John Lydon (Johnny Rotten) makes the most pertinent, interesting comments. He also breaks down when talking about Vicious who, lest we forget, had been a friend from before the band started. He died, Lydon says, reminding an audience of the often ignored obvious.

“Sid was a very interesting human being,” says Temple, “but obviously an addictive personality. He destroyed himself with the heroin but before that he was a wonderful character. I think the interview we have with him shows his humour and an overview of what’s happening and how awful it is to be trapped in addiction.”

And Lydon’s tears remind there was as much

affection as rivalry between the two. But the band was destroyed from both

within and without. After the Grundy show Johnny Thunder and the Heartbreakers

arrived from the States and with them came heroin and Nancy Spungen, the woman

who became Vicious’ girlfriend and drug procurer.

The underground was dragged into mainstream attention, Vicious started his relentless slide, the American tour was ill-conceived and McLaren absented himself. It was over.

Temple filmed Vicious’ My Way video: “Getting him out of bed was the main job on that shoot. But in a sense the group was always destined to end, they certainly weren’t a 20-year plan of a rock band.”

Today Lydon lives as an exile in Los Angeles: “It’s an odd city for him to be in because he’s so connected to England. Say what you like about him, he is what he is. He certainly hasn’t mellowed.” But punk has been and gone and the crucible in which it was created is different now. It’s been done.

“It won’t happen again in that way,” says Temple, but that doesn’t mean something else won’t happen. I hope it will. It’s overdue.”

post a comment