Graham Reid | | 2 min read

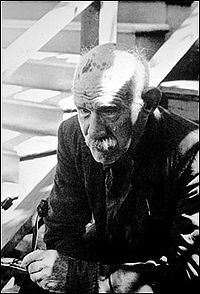

When the reclusive and friendless Henry Darger died at 81 in Chicago in 1973 (after a brief period in the same poorhouse in which his father had died) his story really began.

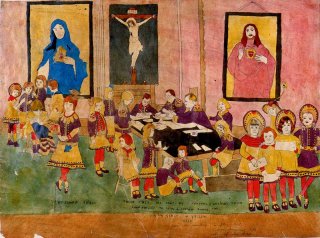

Shortly before his death his neighbours discovered that Darger's apartment was full of the most remarkable, sustained artwork. Over the course of his later life -- in the absence of the distractions of company, television, radio and so on -- Darger had written and illustrated an epic story which ran to some 15,000+ pages.

That manuscript -- entitled The Story of the Vivian Girls in What is known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinnian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion -- is steeped in religion, a love of children (he drew the naked young girl with penises, perhaps because he knew no different?), autobiographical exorcism and much more.

Darger had an emotionally cold life: as a child he lived with his father after the death of his mother; was put into an institution (he may have been ADHD); was bullied and ostracised; ran away back to Chicago; served briefly in the army; and then for the rest of his life supported himself as a janitor and cleaner while he wrote his beautifully illustrated epic. He had taught himself to draw (material sourced from comics, old books and posters found in rubbish bins) and although his work is considered Outsider Art he had a keen eye and good sense of design.

Darger was also profoundly religious and attended the nearby Catholic church daily, although it is telling that in this remarkable, award-winning documentary that people's opinion of where he sat in church varies widely. Each will attest with certainty that he always sat either at the front, the back or in the middle.

Since his death more of the oddly introverted life of Darger (people also differ in how the name was pronounced) has become known but during his lifetime he was, as one neighbour says, an invisible man. There are only three known photographs of him.

His massive manuscript -- here animated in places, and read Larry Pine with Dakota Fanning telling of Henry's life -- is full of allusions to God and Jesus and redemption, and the evil enemies who would be cruel and hurtful to children. It can be delightfully pretty and also brutally violent.

This documentary sensibly keeps the focus on Darger's life and work, with brief commentary by the few neighbours who had anything to do with him. Mercifully no art experts are trotted out to explain his significance.

It is obvious that Henry Darger was a singular individual whose work belonged to no school and owed its existence solely to his imagination and the thousands of hours he devoted to drawing, writing, compiling and considering.

He may have been a man with no visible "life", but his internal world was full of joyful or terrifying companions.

post a comment