Graham Reid | | 2 min read

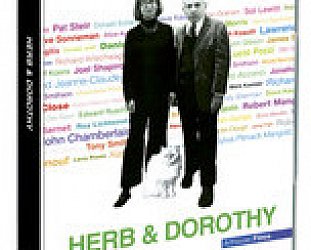

In a recent documentary Drilling for Art, the spotlight was put on Dubai as a place with no art history (other than some minor folkloric things) and a city where 95 percent of people come from somewhere else.

A few years ago Dubai decided it needed Art -- and so in tentative steps started encouraging contemporary galleries to open, and invited in orchestra leaders and educated expats to give the country a cultural kick. When the economic downturn hit of course the whole thing just folded -- but it was emblematic of how many emerging nations, countries and cities want Art as another thing to either brag about or exploit in the service of their national profile for the West.

China's contemporary art scene is more layered and therefore more problematic: for the populace and political leaders it means accepting a shift from the collective to the individual, from propoganda to the personal -- and to some small extent China's masters want it to happen now, be uninhibited (but carefully controlled) and create then feed a market.

The ruling elite have seen that contemporaary art demonstrates "openness" and that plays well in the West.

As this fascinating and usefully sceptical doco illustrates, the tensions between the booming art market and social controls, the avant-garde and the old world, and within the artistic communities themselves, are often flinty and remain precariously unresolved.

Since the death of Mao and the courageous (if scrupulously polite) manifesto of the Star Group -- and the No Name Group -- in '79, contemporary art in China has rapidly moved through a number of phases: the schism between political pop and cyncial realism is neatly outllined -- and of course there has long been the West's infatuation with Mao-chic which is frequently artless and shallow.

That of course hardly troubles the gleefully hand-rubbing curators, marketers and gallery owners who now see work (some of it crass and emotionally empty) commanding six and seven figures in the auction houses.

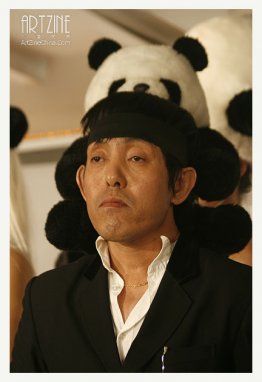

Some serious artists and observers here are understandably cynical, others like the panda-obsessed Zhao Bandhi could either be the new Warhol or a whimsical dilletante whose work charms locals and European catwalks but is utterly irrelevant to any serious discussion.

And there is serious discussion in China Power: about the problems inherent in the government creating museums and galleries, artists in exile, the commodification of art, the return to sentimentality for the days before Mao and the Cultural Revolution . . .

China Power is an insightful, intelligent and useful overview of how China has emerged from the Cultural Revolution to have its artists exhibiting in a forum like the Venice Biennale (even if some of it isn't much cop) and a few artists (Cao Fei, Ai Weiwei) being rightly recognised internationally.

Not sure about the panda guy though.

post a comment