Graham Reid | | 2 min read

More than a documentary about the great American artist Chuck Close -- whom we see work on an astonishing self-portrait during the course of the filming -- this remarkable, revealing and important film weaves in the work of many of Close's contemporaries (Richard Serra, Robert Storr and others) and has friends and longtime colleagues (Philip Glass among them) speak about Close' significance . . .

And how his paintings affected them personally and professionally.

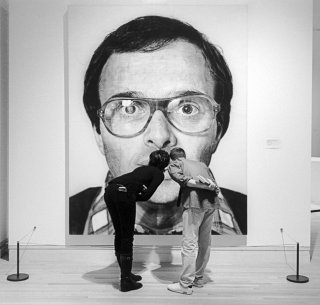

Close's early work - massive in scale, intimate in their detail -- were portraits in which he explored every pore.

Rather than viewers recoiling at the size and unflattering detail that such work allows, they are drawn in to the work.

Much as newspaper photos disappear into dots the closer you get, so the faces and bodies become abstract works the nearer you go.

In his early years Close refused to have his paintings in New York galleries which showed portraits but insisted they be shown where Abstract Expressionists exhibited. He had a point.

Working from photographs divided into grids -- which he admits some people saw as cheating, but the grid has a history dating back centuries -- his works were extraordinary for their detail.

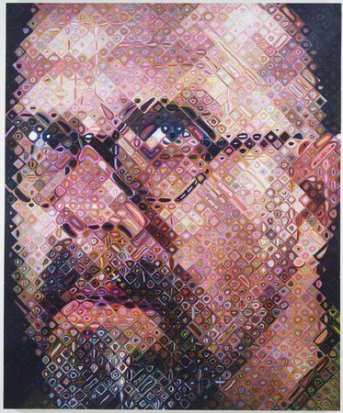

A stroke in '88 changed everything and since then -- as this film shows -- Close has been in a wheelchair and working with an arm strap which allows for him to hold brushes.

His method and style obviously underwent fundamental changes and a new, almost molecular energy developed from the same working method.

In the grids now, rather than replicating as closely as possible the surface colours and textures from th photographic image, glow with quilt-like vibrancy and abstract rectangles.

The great irony in Close's life isn't that he has been so fundamentlly changed but that this man, whose career has been on the back of what many simply see as portraits, suffers from prosopagnosia, a condition whch means he doesn't recognise people's faces, even after a number of encounters.

This engrossing film -- where his self-portrait emerges over a period of three months -- also shows Close as witty, enjoying life (wine and fine food) and a poor whistler (he plays Nina Simone and Paul Simon in his studio and whistles along tunelessly).

This was one of the last docos filmed by Cajori who died in '06.

It is a remarkable testament to her insight and patience, and the trust she enjoyed in eliciting such insightful comments from the artist, his wife, critics and friends -- and of course a fine statement about one of America's most important contemporary artists.

post a comment