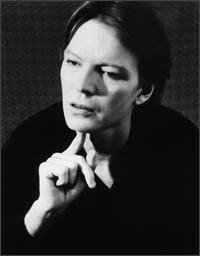

Graham Reid | | 9 min read

Jim Carroll: Reading from The Book of Nods (1981)

Keep a diary and some day it’ll keep you. -- Mae West.

The blizzard which has engulfed New York has abated a little although snow is still piled over parked cars and a flesh-freezing wind whistles between the tenement blocks.

And Jim Carroll - former junkie and rock singer, writer, poet and most recently movie actor on the strength of a cameo slot in the film adaptation of his The Basketball Diaries - has to go out.

“Yeah, this art exhibition down in

SoHo. Like, I don`t even know where it is and ahh . . . I have to go

over to my friend Harmony’s house and Chloe . . . you know the

movie Kids, well Harmony’s ahh, he’s, like, the guy that wrote it

and Chloe plays ahh . . . you know, the female lead and the girl

that’s having the show is, like, Chloe’s best friend, you know

...”

When Jim Carroll talks it is with a

cracked hesitancy punctuated by long pauses. Like Lou Reed’s New

York album slowed to half speed.

But yeah, he has to go out, like, in

maybe 10 minutes but ahh . . .

An hour later he’s still talking,

joking about spoken word guys like Henry Rollins: “We don`t see eye

to eye, he dissed me in some magazine - but I find what he does very

tiresome. He and others from the rock scene think poetry has some

hideous connotation. It’s always been okay with me!”

Or he's laughing about that cameo where

he plays a strung-out junkie like some Italian hipster he knew as a

kid: “I just wish they’d lit me better. I look like I just rose

from the dead. I did another scene I liked better which was the

original ending, me doing my David Caruso impression!"

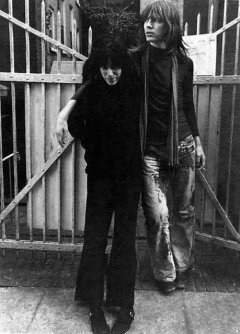

Or talking about Patti and Lou: “Patti

and I did a reading recently in Seattle at the opera house, a very

elegant crowd.”

And that’s Jim‘s world. Patti Smith

and Lou Reed are longtime friends, he walks through gallery openings and the

hip film crowd, has just seen another of his pieces (“just a

12-page story”) made into a feature film which won awards at

Toronto and Berlin film festivals, is writing the outlines of a

couple of novels and turning down more cameo roles.

And that’s Jim‘s world. Patti Smith

and Lou Reed are longtime friends, he walks through gallery openings and the

hip film crowd, has just seen another of his pieces (“just a

12-page story”) made into a feature film which won awards at

Toronto and Berlin film festivals, is writing the outlines of a

couple of novels and turning down more cameo roles.

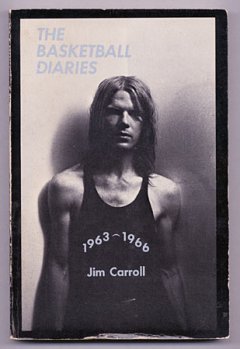

But it wasn't always so as the journal

of his youth, The Basketball Diaries -- a wired Catcher in the Rye,

excerpts of which were first published in the influential literary

journal The Paris Review in the late Sixties – attest.

Jim was the Catholic boy who made the team, won a scholarship, sniffed glue, smoked a lot of dope and ended-up with a habit.

But through it all he wrote and now, more than

15 years after it was first touted as a film property, the acclaimed

The Basketball Diaries has made the big screen.

With Leonardo DiCaprio, who bears an

uncanny likeness to the young Jim (“That’s what Lou says too, but

he’s so sardonic. I wasn’t quite as thin!"), the film

appropriates sections of the book into a continuous narrative and

weaves a story out of what were adolescent diaries never intended for

publication.

Carroll likes the film but “I sold

the option every year practically so it’s been a nice stipend for

me. I feel bad it’s not there now." He laughs like an

asthmatic jackal again and the creaking monotone rolls off into yet

another stream-of-consciousness anecdote.

Carroll is an easy conversationalist

and his language betrays his literary leanings. Something was

“germane” to the movie, he didn’t “vouchsafe” those high

school photos to the movie company and it was “happenstance thing”

he was “recording a radio show at the Electric Ladyland studios

when Rancid were recording downstairs and so that’s how came to be

on their album doing that rap in one of the songs and one of the

lines I said was ‘and out come the wolves’ and so that became the

title of their album”.

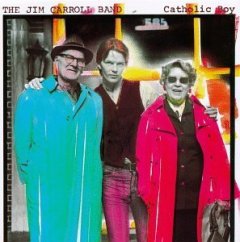

It’s hard to believe this creaking

monotone full of sudden stops is the same voice that wrapped itself

around some edgy if patchy rock’n’roll albums (Catholic Boy, Dry

Dreams, I Write Your Name) back in the early Eighties, which mostly

catalogued his life in songs such as People Who Died -- a litany of

dead friends – which reappears on The Basketball Diaries soundtrack

alongside Soundgarden, the Cult, and the Doors.

It’s hard to believe this creaking

monotone full of sudden stops is the same voice that wrapped itself

around some edgy if patchy rock’n’roll albums (Catholic Boy, Dry

Dreams, I Write Your Name) back in the early Eighties, which mostly

catalogued his life in songs such as People Who Died -- a litany of

dead friends – which reappears on The Basketball Diaries soundtrack

alongside Soundgarden, the Cult, and the Doors.

Carroll is the junkie survivor and

today, with the book having bounded up the New York Times best-seller

list in the wake of the film, he’s in demand again, back out on the

college circuit and the occasional rock club doing readings, talking

about another rock album he might do with Lenny Kaye because they

recorded a few songs together (and with Pearl Jam) for the soundtrack

but which didn’t make the final selection . . .

The book always sold, he says, but he

was worried if the movie was no good it would stop sales. “I like

the idea of film, but to me my work is the book.”

What has ensured the success of the

film -- aside from DiCaprio’s mesmerising performance and a strong

ensemble which includes rapper and Calvin Klein poster-boy Mark

Wahlberg (Marky Mark) -- is its slightly anachronistic timelessness.

Written between 1963 and '66, the book

has been pulled gently into the Nineties by the contemporary rock

soundtrack but, as Carroll notes, “they really put it in no time,

but that time is now.”

His original idea back in the early

Eighties, when a young Matt Dillon was touted as the lead, was to

have period music by Dion and the Belmonts to keep it a Sixties

setting.

“The first time I saw the film was

with Lou and it didn’t have the soundtrack and he’d just done a

song for that tribute album to Doc Pomus [Till the Night is Gone] and

he thought that song [This Magic Moment], real New York stuff, would

be good because he thought it was in that period. So there’s not

much in the film to pin it in time.

“Like, they told Marky he couldn’t

wear his B-boy clothes -- but when they are playing basketball they

wear those long baggy shorts. So, I dunno ...”

He admits he was down on Marky Mark at

first but the controversial rapper (who has sounded off about gays in

the past) auditioned seven times “so I thought I shouldn’t hold

his paraphernalia against him . . . and Leo didn’t like him much

but now they’re great old buddies.

“But the performances are great. I

talked a bit to Leo but said nothing special. They had some drug guy

-- who I actually knew, he used to be a roadie for the Blue Oyster

Cult -- and he was telling Leo what to do in the drug scenes."

But if Carroll has an objection to

anything in the adaptation it's the moral agenda about drugs,

something neither his book nor music have ever done. Promotional

video interviews with the actors show them advancing the anti-drug

message too.

“I liked the screenplay on paper and

made a few changes and what I liked best were the voice-overs

straight from the book. But then they changed the ending.

“The original ending was shot in New

York but then they flew Leo and people out to LA for that whole

poetry reading and he read a different piece. It just became too much

of the drug cautionary tale thing and they assured it wouldn’t be

like that, just neutral like the book. But I didn’t have any power

at that point.

“I saw a lot of possibilities in

Ernie Hudson’s character [as the black hoop-shooter who attempts to

cure Jim in an enforced cold turkey] because he was interested in

writing and the film didn’t show the development as a writer. It

misses a big part of the book. Every screenplay I’ve seen had some

flaws, they concentrate on the early years or the later years and

Catholicism, most all have concentrated on the fish-out-of-water

aspect of getting a scholarship to the exclusive private school . .

.but they didn’t use that in this! They made it like I was in

Catholic school all the time. The film works best when they left the

camera on Leonardo and the cast.

“And my writing and song lyrics

basically are very ethical in a certain way and I've always felt you

could find some purity inside the worst degradation, some sense of

light. But as far as the heroin thing, when I was writing I was so

young I couldn’t make any moral conclusions. I was just writing

down what happened and I think that's the appeal of the book . . .

but it’s not unusual a film adaptation takes on some moral aspect.

“It surprised me though because that

was a really big thing they weren’t going to capitulate to that.

It’s always been a problem because the end of the book is very

literary with him just looking out his window after his three day run

where he has his first habit.

“I guess you have to tie up the ends,

like walking down the street or die. I thought it would have been

better if they’d killed me off."

He cackles again and gets an even

bigger laugh out of the film’s promo tag “the death of innocence

and the birth of an artist”.

“I was in a movie theatre when they

played the trailer and they used that line and said ‘this is about

JIM’ in this big stereo surroundsound. My friends just had

hysterics.

“And I don’t think my innocence was

dead. It was just tarnished and there are many forms of innocence. I

still haven't exhausted all aspects of it.”

As one who has seen himself marked

before -- CBS Records tried to sell him as the authentic voice of New

York's rock’n’roll mean streets for those albums – he is

cynical about the promotional trailers for the film which variously

present the movie as either A Hard Day's Night (lots of running

freely down the street), a hippie trip (one trailer snips out the

sole psychedelic scene) or a teen movie (DiCaprio and his buddies

joking it up).

As one who has seen himself marked

before -- CBS Records tried to sell him as the authentic voice of New

York's rock’n’roll mean streets for those albums – he is

cynical about the promotional trailers for the film which variously

present the movie as either A Hard Day's Night (lots of running

freely down the street), a hippie trip (one trailer snips out the

sole psychedelic scene) or a teen movie (DiCaprio and his buddies

joking it up).

But Carroll freely admits to long ago

having given away attachment to the book, the film and the young boy

that was once him.

He refers to the boy in the book in the

third person and how works of art stand on their own, he says,

outside of their creator. They take on an independent life over which

the artist can have no further control. It’s like a painting, he

says . . . and, before embarking on another analogy or illustrative

anecdote, is reminded that he has something he should be doing.

"Oh, yeah, I gotta go to this art

opening, gotta meet my friends, Harmony and Chloe, like ahh, you know

. . ."

And Jim Carroll’s back on the

streets.

Jim Carroll died in September 2009,

he was 60.

post a comment