Graham Reid | | 3 min read

The art critic Robert Hughes didn't have much time (but some sympathy for) New York painter Jean-Michel Basquiat. In a brutal essay in The Republic in '88 -- after the death of the painter at age 27 -- entitled Requiem for a Featherweight he pulled no punches.

The truth abut Basquiat, then the most famous painter of his generation, was, according to Hughes "a tale of a small untrained talent caught in the buzz-saw of art-world promotion, absurdly over-rated by dealers, collectors, critics and, not least, himself.

"This was partly because Basquiat was black; the otherwise monochrome Late American Art Industry felt a need to refresh itself with a touch of the 'primitive'."

Hughes further noted Basquiat had started in graffiti and "graffiti were in fashion in the early Eighties and collectors were ready for a Wild Child, a curiosity, an urban savage -- art's answer, perhaps, to the Wolf Boy of Aveyeron. Basquiat played the role to the hilt."

In the end it killed him of course. He became increasingly dependent on hard drugs, was feted as a celebrity which he sometimes enjoyed and at other times felt uncomfortable about, became ridiculously prolific to feed a greedy and ceaselessly demanding market (when he died after just six years as a working artist he left 1000 paintings and 1000 drawings) and was burning himself out.

His champions -- mostly dealers, collectors and those with a vested interest as Hughes points out -- spoke of him in the same breath as Picasso and used the word "masterpiece" about his every scribble.

In this fascinating and not entirely uncritical doco, those champions are on display but their words -- especially if you keep Hughes' opinion in mind -- ring increasingly hollow.

Basquiat was a phenomenon, but you could argue one more of the marketplace than in the annals of art history.

Yet there is undeniably powerful work shown here and Basquiat does come off in interviews as self-aware, cautious and intelligent. But too often you see works which are mere cyphers and shorthand, suggesting or evoking much more than they are actually delivering.

Baquiat came to the art world through graffiti (he and a pal scribbled urban koans on walls as SAMO - Same Old Shit) but once he had access to paint and a surface -- doors, windows, tnen canvases -- he produced some exceptionally muscular and/or refined works which were as distinctive as they were arcane, personal and coded.

Baquiat came to the art world through graffiti (he and a pal scribbled urban koans on walls as SAMO - Same Old Shit) but once he had access to paint and a surface -- doors, windows, tnen canvases -- he produced some exceptionally muscular and/or refined works which were as distinctive as they were arcane, personal and coded.

There was just three years between his "early" works and his "later" works, which shows how fast the market was moving in that "greed is good" decade.

Hughes: "Basquiat's career appealed to a cluster of toxic vulgarities. First, the racist idea of the black as naif or rhythmic innocent, and of the black artist as 'instinctual,' outside mainstream culture and therefore not to be judged by it: a wild pet for the recently cultivated white. Second, a fetish about the infallible freshness of youth, blooming amidst the clubs of the downtown scene. Third, an obsession with novelty . . ."

And he goes on to tick of six such damning points, all about the milieu not the artist.

Yet Basquiat was aware of all these things.

Here when asked if he is a "primal Expressionist" he looks both amused and cynical, like a primate you mean, he asks. His earnest inquisitor looks uneasy and uncomfortable, as if he has been rumbled.

This doco places Basquiat in that context, allows for a couple of disenting voices (not Hghes unfortunately, although he may well have hogged the scene) but mostly lets the word "masterpiece" be bandied around with careless disregard and the cult of Basquiat to be given nourishment again.

Look at the title of this doco and ask yourself . . .

The cult of Basquiat hasn't dissipated with time -- indeed he has come to be seen as emblematic of the New York art/culture scene in the Eighties when Basquiat was under Warhol's wing -- and Hughes' final sentence in his essay is worth considering.

The cult of Basquiat hasn't dissipated with time -- indeed he has come to be seen as emblematic of the New York art/culture scene in the Eighties when Basquiat was under Warhol's wing -- and Hughes' final sentence in his essay is worth considering.

Noting that soon after his death one of Basquiat's painting sold for US$300,000 Hughes speculates, "it will be interesting to see what it makes the next time around, when the hysteria has cooled a little".

Exactly 20 years after Hughes wrote those words one of the many celeb-collectors of Basquiat's works (which included Madonna who was briefly his lover, of course) put a painting on the market.

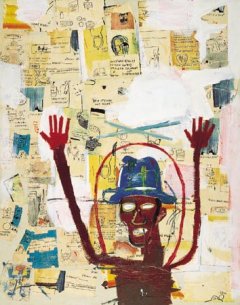

Lars Ulrich of Metallica got US$13.5 million for The Boxer (above).

Interested in this? Then check out this.

post a comment