Graham Reid | | 2 min read

Allen Ginsberg: Footnote to Howl (reading from 1956)

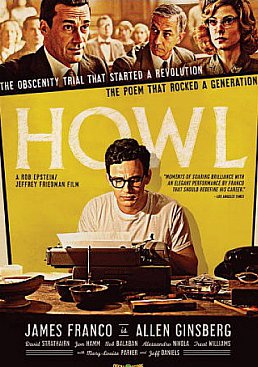

The three parallel, intercutting narratives here in this story of Allen Gisnberg's famous, half-hour poem Howl and the subsequent obscenity trial can be off-outting at first, and in truth don't serve the film or poet especially well. But for those new to the subject its slightly racy, post-modern attitude is bound to have considerable appeal.

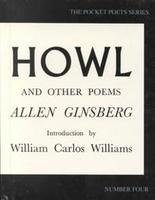

Generations have grown up with the first lines of famous poems drilled into them at school -- "I wandered lonely as a cloud", "The Assyrian came down like a wolf on the fold" and "Faster than fairies, faster than witches" all come to mind in my case. But Ginsberg's work cut like a blunt blade into the consciousness of the Fifties and beyond, and it wasn't taught in schools.

The inescapable, "I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix, angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo of the machinery of night . . ." imprinted itself by sheer visceral, confessional force.

And even if some of the imagery was confusing at first -- a point some accusers made at the trial of City Lights publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti -- the cumulative effect was of a freewheeling world of Beat poetics, graphic homosexual acts of love and eroticism, transcendant spiritualism, open-heartedness and the pounding rhythms of bebop jazz.

Howl was a landmark in American poetry when Ginsberg first read it in 1955 and its ripples spilled into subsequent generations, notaby the counterculture of the Sixties. It staked out the territory of the Beats and opened the world to Jack Kerouac, Gary Snyder, William S. Burroughs and many others. It's trickle-down was still being felt when Patti Smith, Jim Carroll and others came along brandishing their own style of hip, New York-infected poetry in the mid Seventies.

Howl was a landmark in American poetry when Ginsberg first read it in 1955 and its ripples spilled into subsequent generations, notaby the counterculture of the Sixties. It staked out the territory of the Beats and opened the world to Jack Kerouac, Gary Snyder, William S. Burroughs and many others. It's trickle-down was still being felt when Patti Smith, Jim Carroll and others came along brandishing their own style of hip, New York-infected poetry in the mid Seventies.

Here James Franco as Ginsberg (reading, later being interviewed) does an excellent job, especially in his note-perfect delivery of Ginsberg's cracked and slightly croaky, pause-filled voice in the black'n'white interview sequences as he waits at home while the trial proceeds.

The courtroom sequences -- staid, somewhat cliched characters, a damp denouement stripped of any tension because the result is predictable if not already known by the audience -- are the least successful elements.

The third aspect is a visually rich and evocative animation of Ginsberg's words (by artists in a Thai studio) which - when added to Franco as Ginsberg in explanatory/confessional mood -- illuminate the many layers of the poem and especially it's autobiographical nature.

Going unexplored is that knotty contradiction at the heart of Ginsberg's work, that he was reluctant to publish because he was fearful of what his family might think, but also lapping up the attention it had brought him when he read it.

So a flawed but not uninteresting attempt to evoke a period where poets could drive a stake into the conservative heart of a nation and actually make a difference.

Howl is, for that reason alone, a remarkable piece of work -- and those opening lines still burn like branding iron.

Like the sound of this? Then check out this.

post a comment