Graham Reid | | 4 min read

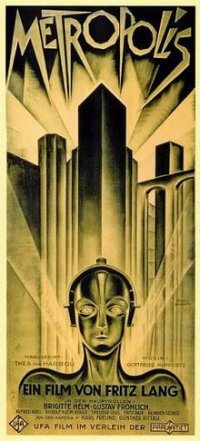

Because it was, and remains, such an extraordinary film on every level -- visually, philosophically, technically -- most people can remember their first encounter with Fritz Lang's 1927 masterpiece Metroplis.

Unfortunately, I suppose, many today encounter it in a Film Studies 101 course where it is shown in a lecture theatre in the context of analysis or as part of a homework assignment, as opposed to the thrill of discovery. It is a film -- like Lost Horizon or The Shape of Things to Come -- you really need to see on a cinema screen, no matter how meagre that screen might be.

That was certainly my initial encounter with Metropolis.

It was the Classic Cinema on Queen St on a wet weekday afternoon in perhaps the very late Seventies and -- never having seen it, but knowing the mythology -- I went along to be one of only three people in the uncomfortable cinema to see this classic which is every film encyclopedia.

My other two companions on the day were cold itinerants, sad alcoholics, who stumbled in together then sat at a great distance from each other and, mercifully as it turned out, from me.

There was an unannounced and uncredited 20 minute short -- the Beatles playing their first US concert in '64, poor quality but absolutely thrilling and which didn't turn up on DVD until many decades later. I have no idea what the alkies thought of this but for me it was an unexpected bonus (and frankly I would have advertised that and not some flickery b'n'white old film if I'd wanted to draw the punters).

But within minutes of Metropolis starting my two companions were sound asleep, one of them snoring loudly.

I watched the film unveil before me and it was an extraordinary experience. Metaphorical, symbolic, messages laid on with a trowel, grandiloquent, subtle sometimes, full of memorable images . . .

Just before the end one of the old guys (they seemed old to me in my 20s, they might have been in their booze-damaged 50s) got up and shouted "fascism" at the screen and then made his way to the toilet. This roused the other who announced "capitalism!" at the top of his voice and also headed off to the bathroom where I imagined a fascinating political conversation must have taken place.

Me? I just sat there and stared at the empty screen and was baffled -- in a good way -- by what I had just seen.

Years later I saw the film again and again, and now have spend days going though this double disc DVD which restores as much of the original film as is available. (I had no idea that about a quarter of it had been lost until a print was found in Buenos Aires). And it occurs to me that either one of those drunks was right in their comment, and could also have yelled out "Futurism" or "Progress" or "Siddhartha" or "Expressionism" and it would have made as much sense.

Metropolis is a film like that.

You can see/read into it a kaleidoscope of ideas and idealogies -- and all the while sit utterly engaged by the sheer conceit of its visual imagery.

It is grand in scope and design, in breadth and depth -- and yes, ladels on ideas with a trowel. Subtle it mostly isn't. But that takes nothing away from it.

Different people, different times, different ideologies and -- we might say -- a balance of cynicism and hope in those years after World War One and when the Next Big One was still an unexpected decade away.

Different people, different times, different ideologies and -- we might say -- a balance of cynicism and hope in those years after World War One and when the Next Big One was still an unexpected decade away.

It was the time of the Grand Gesture, and Metroplis was certainly that: 36,000 extra, 1100 shaven heads and 200,000 costumes.

It cost the Ufa studio five million Reichsmark to produce. It brought in only 75,000.

It was the Heaven's Gate of its day -- except it was a timeless artistic statement and not the overblown dog that Heaven's Gate was.

It was a time when Big Science was something which offered hope although it existed outside the mainframe of most people, when industrialisation offered work (but also mindless drudgery, a path Chaplin, pictured above, also went down on Modern Times almost a decade later), and of course salvation would come in the form of . . .

Let's not spoil it.

Metropolis is a film which demands to be seen.

Metropolis is a film which demands to be seen.

Not for a homework assignment, but because it is so exceptional, philosophically problematic, complex but simplistic, and so dated that it has almost come around again.

It still matters.

It also looks exceptional and this reconstructed edition -- which takes the original out to almost all of its original two and a half hour running time -- and comes as a two DVDs with oceans of extra material placing it in the context of its time and so on.

The substantial accompanying booklet has comments and essays by Terry Gilliam, Mamouru Oshii and others.

On the extra disc is the doco Journey to Metropolis which recounts the reconstruction process, shows working sketches (nope, that isn't Bladerunner, just looks like it) and locates the film within the domestic and industrial architecture and photography of Germany and New York at the time . . . and also takes you in to Lang's weird, traditionally Germanic apartment home from which this oddly futuristic vision emerged.

Okay, Metropolis is exceptionally long, slow, manner, laboured . . . and of course is a silent film with insert cards (and a new recording of Gottfried Huppertz' original score).

But . . .

But it doesn't feel like a homework assignment, and at the end just try to pick one word you think you might have bellowed out in an empty cinema on wet weekday after you had seen it.

"Brilliant" would be mine.

Footnote: Of course some may have seen Metropolis in re-issue in the early Eighties when Giorgio Moroder had Freddie Mercury, Bonnie Tyler and others add music. But really?

Did no one think of music by those great Futurist/industrialists Kraftwerk?

Too obvious perhaps.

post a comment