Graham Reid | | 5 min read

The Light That Has Lighted The World (demo)

Five years ago, longtime Abbey Road studios engineer Geoff Emerick – who was there for the first and last Beatles' recording sessions and only missed a few weeks in between – wrote an interesting, slightly jaded but perhaps uncomfortably true memoir, Here, There and Everywhere.

Aside from

undermining the conventional wisdom that producer George Martin was a

pivotal figure in many of the band's most innovative recordings from

1966 onwards – he was often absent, says Emerick – he was also

disdainful of George Harrison's capabilities.

"[George] was having real difficulty nailing it” and “the weak link that day was George Harrison who seemed even more ham-fisted than usual as he gamely plowed his way through one mediocre guitar solo after another” are typical comments which ring like refrains about Harrison's technical shortcoming in the early years.

Out of frustration Paul McCartney would often take over.

And in later years, according to Emerick, Harrison became an annoying perfectionist, or failed to nail a complex song. His Not Guilty required 99 takes . . . and still didn't make it onto The White Album.

He was however very pleasant when he wanted something (although protective of his biscuits!) and a sensitive producer of other artists like Jackie Lomax on whose sessions Emerick also worked.

Aside from delivering some dull solo albums and more than a few misanthropic or finger-wagging songs, George Harrison has always been respected as the quiet, spiritual Beatle.

He was the one who changed the most from being a young man with a lop-sided smile who played single-string country-flavoured guitar solos to being a champion of Indian philosophies and Ravi Shankar, and who was the instigator behind the Concert for Bangladesh in 71, the first great charity fundraiser of the rock era.

Harrison was also the

spiritual seeker who bankrolled Monty Python's Life of Brian to the

tune of multiple millions by mortgaging his beloved stately home

simply because he wanted to see it made.

“The

most anyone has ever paid for a cinema ticket,” says the Python's

Eric Idle.

The ukulele-playing, fast car aficionado -- who counted among his closest friends thoughtful gardeners and racing legend Jackie Stewart -- was a complex

character.

The ukulele-playing, fast car aficionado -- who counted among his closest friends thoughtful gardeners and racing legend Jackie Stewart -- was a complex

character.

But there was even more to Harrison as Martin Scorsese's thorough, pointed and fascinating three and a half documentary Living in the Material World reveals.

Cocaine, women, anger, deep resentments . . .

It's always the quiet ones, huh?

Scorsese has previously made excellent inroads into rock films with The Band's Last Waltz and more recently the Rolling Stones live doco Shine A Light.

But the up-close biography Living in the Material World most resembles is his exceptional No Direction Home, the portrait-cum-analysis of Bob Dylan's pivotal decade up to 1966.

As with that film, Scorsese has access to previously unseen footage and comments from contemporaries and those closest to his subject. Ringo Starr (in tears when talking about Harrison's death from cancer in 2001), Paul McCartney, a typically disingenuous Yoko Ono, Harrison's second wife Olivia (who seems to have been long-suffering of his marital indiscretions), Hamburg days friends Astrid Kirchherr and Klaus Voorman, Idle of the Pythons, his son Dhani (who reads from George's letters home to his parents while in Hamburg and on tour in the US) and Eric Clapton all speak of Harrison's personality, music, life and loves.

“We shared the same taste in women” says the candid Clapton, a reference to him falling in love with and subsequently marrying Patti Boyd, the first Mrs Harrison, about whom he wrote Layla.

As with the Dylan doco, this film patiently unpeels its subject – Dylan also a man who went through more in a decade than most of us go through in a lifetime, but conspicuously and unforgivably absent here – and is respectful of Harrison without elevating him to sainthood, slightly coy about his shortcomings but introducing them nonetheless.

Harrison – born to an ordinary working class family – discovered rock'n'roll and guitar, was younger than McCartney and Lennon (a fact they seemed never to let him forget, and which Harrison never forgot) and found himself when he discovered Indian music, Hinduism and a lifelong friend in Ravi Shankar, all of which allowed him to emerge as his own man outside the shadow of the Beatles.

This much is known to most Beatles aficionados – Scorsese provides the details, footage and first-person commentary – but the film also reveals much more.

In his post-Beatles years the quiet one kept things quiet and on the downlow: the cocaine, the women, the darker side . . . Among the previously unseen footage is a razor-thin Harrison clearly coked to the eyeballs, wide-eyed and on the edge as he yelps his way through a concert some time in the early Seventies. Scary.

On the other hand there are some counter-footage, among them him laughing and singing along with his younger self as the video monitor plays a clip of the Beatles' singing This Boy.

Harrison had, according to Monty Python filmmaker Terry Gilliam “grace and humour, and a weird kind of angry bitterness about certain things in life”. Some of that was the trap of being a Beatle, yet more than half the film traces those extraordinary years.

But this leads naturally into religion via Lennon's comments about the Beatles being more popular than Jesus, their realisation that money – of which they had a lot – wasn't everything. There followed the LSD period and then the spiritual search through the giggling Maharishi (doubtless a bewildering figure for those who weren't there at the time when he seemed to make more sense) and meditation.

“He was totally absorbed by meditation,” says Boyd.

“He was into something else,” say actress Jane Birkin about meeting Harrison in this period.

His post-Beatles years with the Krsna movement, taking the Hare Krsna mantra onto the charts, break-up with Boyd and his relationship with the then-tortured Clapton, recording with Shankar and friends, touring when his voice was shot and reviews were cruel, marriage to Olivia, love of motor racing, the Traveling Wilburys, and the terrible attack in late '99 when an intruder tried to kill him in his home . . . all are dealt with. The latter seemed to change him.

The man who wrote Art of Dying when he was 27 now prepared himself spiritually for his own passing. Cancer would claim him soon enough, far too soon. He was 58 when he died in Los Angeles. The ashes of the war baby from Liverpool, raised a Catholic, were scattered in the Ganges according to Hindu tradition.

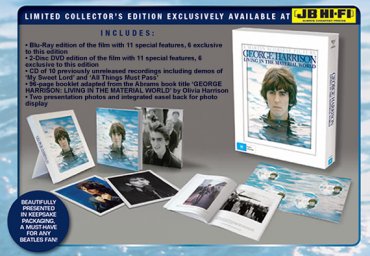

Living in the Material World comes as a DVD and on Blu-ray (both with

extra interviews and music features) . . . but also in a handsome

collectors' edition box set with the film on Blu-ray and over two

DVDs, two framable photos and a 96-page book of quotes and photos,

plus a disc of 10 previously unreleased demos and early takes of some

of his most well known songs.

Living in the Material World comes as a DVD and on Blu-ray (both with

extra interviews and music features) . . . but also in a handsome

collectors' edition box set with the film on Blu-ray and over two

DVDs, two framable photos and a 96-page book of quotes and photos,

plus a disc of 10 previously unreleased demos and early takes of some

of his most well known songs.

(This limited edition is available through JB Hi-Fi here.)

Living in the Material World is an insightful biography of a man who enjoyed – and sometimes endured – a rare life.

“People always say I'm the Beatle who changed the most,” said Harrison in the Seventies with a wry smile, “but that's what I see life is about.”

post a comment