Graham Reid | | 2 min read

Oscar Wilde once observed that fashion is a form of ugliness so intolerable we have to change it every six months. And the cynical observer of the egos and absurdities in the fashion world would doubtless agree.

But a world without fashion? That would be so intolerable we'd want it back in six months.

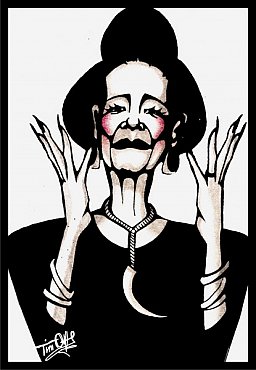

In the rarified air of high style, some characters stand out -- sometimes for all the wrong reasons -- and one of the most enduring if not endearing was Diana Vreeland.

She was born in Paris at the dawn of the 20th century as a socialite by association, nurtured in New York's world of ballet and wealth, running a lingerie shop for selective (and perhaps even selected) clients in London where she was a friend of the aristocracy . . .

Vreeland hardly paused to doubt her specialness as she embarked on a career in the world of fashion and became a pivotal figure at Harper's Bazaar (25 years) then Vogue (eight years).

"Before I went to work for Harper’s Bazaar in 1937," she once admitted, "I had been leading a wonderful life in Europe. That meant traveling, seeing beautiful places, having marvelous summers, studying and reading a great deal of the time."

Vreeland was at the hub of the worlds of fashion, art, culture and the avant-garde with an uncanny knack -- propelled by her self-confidence and eccentricity -- of spotting talent, a trend, a new style and a different way of looking at people, clothes and society.

She was there for the Kennedys at Camelot, in the halls of Hollywood parties and feeling the cultural shifts at Andy Warhol's Factory and the sounds of Swinging London.

From Jackie O to Twiggy to Jagger and Yves Saint Laurent, she was a magpie of ideas and used her influence in the magazines to promote a sense of style and advance the case for some of the most remarkable personalities of our time.

"She had a vision", said Manolo Blahnik speaking for many of those who came in contact with her.

That vision was singular, self-confidence and pushy. It probably marginalised the little people, but it was never going to be for them anyway. Hers was a world larger than mundane reality and came in magnificent black'n'white photographs or was swathed in red velvet.

But as Geoffrey McNabb in the Independent also noted, Vreeland was "one of the sacred monsters of the fashion world: a magazine editor who used to browbeat her photographers and models; who never deferred to her publishers or advertisers and who approached each new issue of her magazines with a messianic zeal".

Vreeland could be a different woman to her family, friends, models and colleagues. She was as much feared as admired, a woman full of assured advice and bon mots as much as someone of a fierce and unusual appearance who might have seemed more suited to playing the Wicked Witch of the West than palling around with the glitterati of Hollywood and New York.

Vreeland has been the subject of a number of books (and an autobiography) but the respectful documentary The Eye Has to Travel by her grand daughter-in-law keeps the focus most intently on the professional life . . . and it looks back not just on a remarkable figure but a period when couture and glamour seemed alluring and the world, if not a better place, was certainly better dressed.

Diana Vreeland -- who died in '89 aged 86 -- wasn't born into, and would have hated, a world of "smart-casual".

And she would have changed it, in considerably fewer than six months.

Want more like this? Guest writer Sarah Jane Rowland considers a doco about New York fashion photographer Bill Cunningham here. And this is about a remarkable museum for the fashion conscious.

post a comment