Graham Reid | | 3 min read

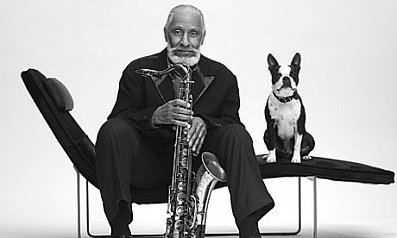

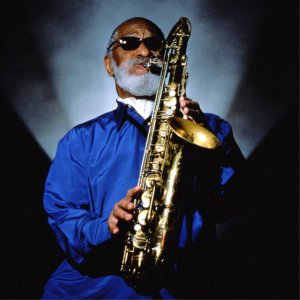

When the great jazz saxophonist Sonny Rollins came to New Zealand in 2011, it was my pleasure to do a phone interview with him beforehand . . . and then see him in concert.

I'd only seen Rollins twice previously and each time they were polar opposite performances, so it was impossible to know what to expect. And similarly interviewing him.

Some musicians can be tetchy subjects, especially jazz and blues players who have often had a lifetime of indifference from the mainstream media, seldom made any money and have to endure what they hear as tedious questions long ago answered.

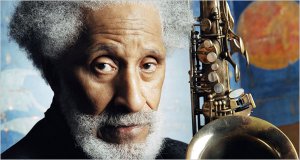

But Rollins, then 80, was pleasant, good-humoured, funny sometimes and always patient.

But Rollins, then 80, was pleasant, good-humoured, funny sometimes and always patient.

He laughed about his 2006 Grammy, saying, “I stayed alive long enough that they finally had to come around to me. I say that because so many of my contemporaries were never really honoured properly. But I'm glad they honour me because they are honouring jazz, not me, and the great musicians I learned from. So I accept them, they're very tardy in recogising jazz.”

Rollins has had an extraordinary life, constantly moving in and out of the spotlight, being surrounded by mythology (the lone saxophonist practicing on Williamsburg Bridge at night during one of his lengthy sabbaticals taken at the height of his fame in the late Fifites) and being hailed as one of the greatest of his generation.

In '67 the young filmmaker Dick Fontaine filmed Rollins at yet another creative peak . . . and then picked up the story again on Rollins' 80th birthday when the saxophonist gathered fellow luminaries Ornette Coleman, Jim Hall, Roy Haynes, Christian McBride and others to celebrate, not himself, but the music they had believed in and advanced over the decades.

In '67 the young filmmaker Dick Fontaine filmed Rollins at yet another creative peak . . . and then picked up the story again on Rollins' 80th birthday when the saxophonist gathered fellow luminaries Ornette Coleman, Jim Hall, Roy Haynes, Christian McBride and others to celebrate, not himself, but the music they had believed in and advanced over the decades.

That insightful Arena doco Sonny Rollins; Beyond the Notes (screening in New Zealand on the Arts Channel, Friday, July 4, 9.20pm) focuses on the Beacon Theatre concert in New York in 2010 and through interviews but mostly from the up-close concert footage, you are gently persuaded by the enjoyable improvising genius that he is.

From the earlier footage we see Rollins speaking about his life and influences -- with clips from Fats Waller, Louis Jordan, Charlie Parker and others -- and as the chronology flicks back and forth over the decades, a picture is built of a generous, serious, well-spoken man who has assimilated much of jazz's complex history and, by being a conduit for it and never losing sight of the music's entertainment value as much as its esoteric art nature, who added and expanded the genre.

Along the way Rollins talks about Miles Davis, Jerome Kern ("one of my favourite composers"), Coleman Hawkins ("my idol"), Thelonious Monk ("my guru, when I started playing with him I was still in high school"), Clifford Brown and Max Roach . . . and a veritable encyclopedia of jazz giants in whose circles he was.

Along the way Rollins talks about Miles Davis, Jerome Kern ("one of my favourite composers"), Coleman Hawkins ("my idol"), Thelonious Monk ("my guru, when I started playing with him I was still in high school"), Clifford Brown and Max Roach . . . and a veritable encyclopedia of jazz giants in whose circles he was.

He speaks candidly about his heroin habit picked up because he knew the great Parker was a user ("I had the wrong idea what it takes to play music"), the shock of trumpeter Brown's death in a car accident in '56 ("a personal loss as well as a musical loss . . . we'd just got to the point where we were breathing together") and those necessary sabbaticals like playing on the bridge when "my name was bigger than I thought I could support with what I was doing . . . I wasn't really playing well enough".

Then in that recent concert he generously introduces a newer generation among them trumpeter Roy Hargrove (who says of playing with Rollins "I felt I was in a room with God") and Soweto Kinch.

This enjoyable, thoughtful and intelligently constructed hour-long documentary is a fine introduction to not just the great Sonny Rollins but also makes the convincing argument for the emotional power of jazz.

No mean feat.

post a comment